|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

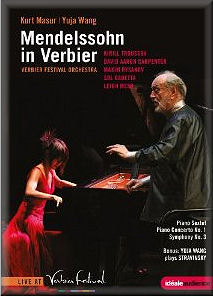

Mendelssohn in Verbier

Felix MENDELSSOHN-BARTHOLDY (1809-1847)

Piano Sextet in D, Op. 110a (1824) [27:27]

Piano Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 25b (1831) [17:05]

Symphony No. 3 in A minor, Op. 56, “Scottish”c (1831) [39:06]

Igor STRAVINSKY (1882-1971)

Three Movements from Petrushkad (1921) [15:51]

acdYuja Wang (piano)

acdYuja Wang (piano)

aKirill Troussov (violin)

aDavid Aaron Carpenter (viola)

aMaxim Rysanov (viola)

aSol Gabetta (cello)

aLeigh Mesh (double-bass)

bcVerbier Festival Orchestra/Kurt Masur

rec. Verbier Festival, abc29 July, d1 August 2009

PCM Stereo. Dolby digital 5.1 Region 0.

IDEALE AUDIENCE 3079248

IDEALE AUDIENCE 3079248  [100:00] [100:00]

|

|

|

Taken from the sixteenth Verbier Festival, this is a remarkable

homage to the evergreen genius of Mendelssohn – with the bonus

of a stunning version of the Stravinsky Petrushka pieces.

The disc begins with the least known piece, the Op. 110 Piano

Sextet. Wang looks rather uncomfortable as she comes on stage,

and even initiates the bow before one of the viola players is

fully in place. All musicians seem to settle immediately down

to the matter at hand, though. The scoring of the sextet is

for piano, violin, two violas, cello and double-bass. Anthony

Short's booklet notes point, correctly, to the influence of

Weber here, particularly perhaps in the sparkling piano writing.

Certainly Wang is beautifully attuned to Mendelssohn's idiom,

and the counterpoint that informs the score is beautifully realised

by all players. Mendelssohn's scoring is rich, even tending

towards the Brahmsian on occasion. The wonderfully interior

Adagio is as delicate as silk, while the relatively extended

finale (8:57) has a sort of addictive energy which is most involving.

Certainly the audience thought so – whoops of joy after the

final chord.

The camera angles are sometimes deliberately close, and a favourite

one seems to be to show Wang through the gap between string

players - they are arranged in front of her onstage. Certainly

one can see plenty of eye contact between the string players

- less so between Wang and her colleagues, but perhaps she wasn't

in shot when it happened. Also David Carpenter finds it difficult

to keep a smile off his face, and he keeps raising his eyebrows

to other players. Wang restricts her witticisms to her fingers;

no flirting there. Her every phrase is a delight, and she sounds

so off-the-cuff that it comes as a surprise to watch her read

the music so closely.

There is no other Mendelssohn Op. 110 on DVD, it would appear,

and this performance is a fine one.

Wang's hair is decidedly wilder in style for the piano concerto

– a seemingly meaningless comment from this reviewer, perhaps,

except to say that it matches her playing. Her sound is perhaps,

a little too shallow for the big choral moments, but the semiquaver

fluency is remarkable, and her diamond articulation fuels further

joy. Masur moulds the violas and cellos in the slow movement

to mesmeric effect – their sound is marvellously rich. Wang

is able to match their eloquence; the experience throughout

is magical. The finale is magnificently sprightly. Perhaps Wang

is a touch too dry in the opening flourishes, and a touch more

wit would be welcome on occasion from her. Still, this is a

noteworthy performance that loses little to the classic (non-visual)

accounts of Perahia, Thibaudet and Ogdon. Masur's contribution

is all one would expect from this ex-conductor of the Leipzig

Gewandhaus Orchestra, with all its links to Mendelssohn.

Masur's reading of the “Scottish” symphony is no less impressive.

He conveys the majesty of the work in tempi which unfailingly

are absolutely right. A special word is in order for the principal

clarinettist, whose solos are uniformly musical, creamily toned

and full of character. The Scherzo reveals virtuoso playing

from just about the whole band, while the Adagio's phrases seem

literally to breathe – one can follow the music's inhalations

and exhalations. The finale oozes energy.

The bonus is the Stravinsky Petrushka pieces. Having

heard Wang play this live in London, it is interesting to hear

her live in Verbier in what is rapidly becoming her signature

work. The dark lighting, complemented by her fire-red dress,

sets the atmosphere perfectly for the fireworks. Yet, for all

the keyboard virtuosity, Wang never forgets that there is the

spirit of the dance at the heart of Petrushka. Her linear

acuity seems even more heightened than Pollini (DG) in the first

piece (the “Russian Dance”), and without his emotional distancing.

The quietly buzzing atmosphere of the Shrovetide Fair is superbly

done, as is the later pianistic frenzy, an orgy of counterpoint

that, even as one hears it, seems improbable. The final chords

approaching the glissando here take on a Mussorgskian element,

something that doesn't even strike the listener with the likes

of Pollini or Kissin. The cheers and standing ovation for Wang

are the natural consequence of her playing.

Wang's Petrushka pieces are available in an audio performance

on her “Transformations” album (DG 4778795 ) - this forms a

valuable appendix.

Colin Clarke

|

|