|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound

Samples & Downloads |

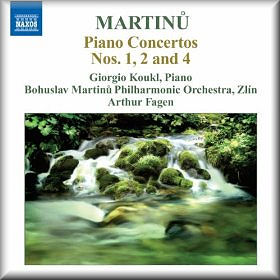

Bohuslav MARTINŮ (1890-1959)

Piano Concertos – Vol. 2

No. 4, H. 358 (Incantation) (1955-56) [20:24]

No. 1, in D major, H. 349 (1925) [29:20]

No. 2, H. 237 (1934) [24:50]

Giorgio Koukl (Piano)

Giorgio Koukl (Piano)

Bohuslav Martinů Philharmonic Orchestra, Zlin/Arthur Fagen

rec. 28—31 May, 2009, The House of Arts, Zlin, Czech Republic

NAXOS 8.572373 [74:45]

NAXOS 8.572373 [74:45]

|

|

|

The major work here is Martinů’s Fourth Piano Concerto,

without doubt the composer’s most intractable and unorthodox

of the five. The concerto is stormy and episodic, not one that

lends itself easily to listener accessibility, but not exactly

a concerto that discourages audiences, either. Yet, for all

its obstinacies and seeming structural detours, it is highly

rewarding. Cast in two movements, it is a concerto that looks

two ways: toward the less serious side of a composer who could

write light music, and toward the more complex side of a composer

who here desired greater expressive depth. In a sense, he succeeds

in both quests: the concerto has many appealing melodic and

rhythmic elements for first-time listeners, but also conveys

a darker more profound expressive manner.

The give-and-take between soloist and orchestra in the Fourth

Concerto comes across strangely, almost with a mutual hostility,

as if conceived in the spirit of separation of church and state:

there are long passages where the pianist either plays unaccompanied

or sits idle while the orchestra takes center-stage. In the

end, the work strikes the listener as a blend of the unsettling

and the mysterious, with, in the first movement, lots of harp

glissandos and occasional activity from the glockenspiel to

fashion mystery, and, in the second, with a darker, eerie sense

to impart uncertainty. The work seems to end triumphantly, however,

and features a somewhat imaginative Gershwinian coda.

The Concerto No. 1 (1925) is neo-Classical and quite light.

It’s what some might think of as cute and clever, and while

that observation might imply a dismissive attitude, I’m suggesting

nothing of the sort. Cast in three movements, it is a work many

will like upon first hearing, with attractive rhythms and themes

and lots of colorful piano writing, and with hints of Liszt

in the second movement. It strikes the listener, at least this

listener, as if it might have been written by a man under the

spell of Stravinsky’s Pulcinella: try the playful opening,

wherein the orchestra states the self-consciously neo-Classical

main theme with an oxymoronic mixture of innocence and mischief.

The Second Concerto (1934) is somewhat closer in spirit to the

First than the Fourth. But it has a few hints of Rachmaninov

and Bartók here and there, especially in the quieter moments

of the first movement. That said, the work is really not imitative,

at all—it’s pure Martinů, always seeming to go its own,

rather distinctive way, with colorful, often playful piano writing

and more than a few whiffs of Czech exoticism.

Pianist Giorgio Koukl turns in fine work, matching the high

level of artistry he achieved in the first

issue in this series, which contained Concertos 3and 5 and

the Concertino. His dynamics and articulation, as well as his

grasp of staccato writing, brilliantly capture Martinů’s

coloristic effects and eclectic nature. Other past Czech pianists

on various Supraphon recordings, like Jan Panenka, Ales Bilek

and Josef Palenicek, were also effective, but Koukl is at least

their equal and often their superior in these performances.

But comparisons are almost a moot point, as Koukl’s cycle is

apparently the only one currently available, and non-cycle issues

of the concertos are sparse. Arthur Fagen draws excellent playing

from the Bohuslav Martinů Philharmonic Orchestra, and Naxos

provides vivid sound. Listeners willing to give the five Martinů

concertos a chance should find most of them quite rewarding

and well worth their attention.

Robert Cummings

|

|