|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

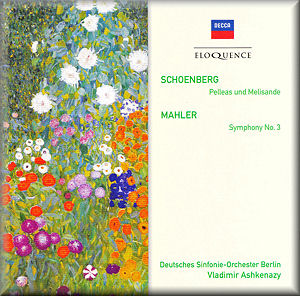

Arnold SCHOENBERG (1874-1951)

Pelleas und Melisande, Op. 5 [41:18]

Gustav MAHLER (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 3 in D minor (1893-1896, rev. 1906) [97:36]

Iris Vermillion (mezzo); Staats- und Domchor Berlin, Knabenchor an der Hochschule der Künste Berlin, Frauen des Rundfunkchors Berlin, Deutsche Sinfonie-Orchester Berlin/Vladimir Ashkenazy

Iris Vermillion (mezzo); Staats- und Domchor Berlin, Knabenchor an der Hochschule der Künste Berlin, Frauen des Rundfunkchors Berlin, Deutsche Sinfonie-Orchester Berlin/Vladimir Ashkenazy

rec. January 1996, Jesus-Christus-Kirche, Berlin (Schoenberg); August 1995, Konzerthaus/Schauspielhaus, Berlin (Mahler)

DECCA ELOQUENCE 480 3479 [75: 00 + 64:14]

DECCA ELOQUENCE 480 3479 [75: 00 + 64:14]

|

|

|

Vladimir Ashkenazy’s recording career – as a conductor, rather

than a performer – began with a distinguished Sibelius cycle

for Decca some thrity years ago. Since then he’s added some

gripping Shostakovich – the RPO Fifth Symphony and St.

Petersburg Eleventh spring to mind – and a top-notch

version of Prokofiev Cinderella from Cleveland. In the

concert hall I have fond memories of him directing a performance

of Alexander Nevsky as an accompaniment to Eisenstein’s

epic film. What an evening that was! Indeed, Russian repertoire

seems to play to Ashkenazy’s strengths – as John Quinn’s review

of his new Rachmaninov cycle confirms – which is why I’m a little

wary of his foray into Mahler and Schoenberg.

Pelleas und Melisande – also in the key of D minor

– is the first work on this twofer, although I imagine most

buyers will be more interested in the Mahler. Recorded a decade

and a half ago, both performances have been reissued by Eloquence,

whose Ansermet Edition has given me much pleasure in recent

years. The sonics of the latter are especially pleasing, the

product of a golden age that Decca – now part of Universal –

have never been able to repeat. That said, their choice of Berlin’s

Jesus-Christus-Kirche – a justly celebrated recording venue

– bodes well for the darkly intense world of Pelleas. But

does the performance come up to scratch? No, is the

simple answer. Comparing this recessed – and strangely episodic

– account with Robert Craft’s (Naxos 8.557527) one longs for

the sensuous throb of sound the latter draws from the Philharmonia,

not to mention the sense of a cohesive, compelling narrative.

Yes, the German band play with poise and delicacy where required,

but the emotional temperature seldom rises above lukewarm. Ashkenazy

is just too dogged, too literal, in music that is convoluted,

fantastical, and not even the hallowed Berlin acoustic can rescue

this lacklustre performance. Indeed, that other iconic venue

– No. 1 Studio, Abbey Road – gives the Craft recording a depth

and richness that is simply thrilling.

So, no contest there. But what about the glorious sprawl that

is Mahler’s Third Symphony? There’s stiff competition

here: at random, Claudio Abbado’s DG versions with the BPO and

VPO; Michael Gielen’s on Hänssler; and, more recently, David

Zinman’s Tonhalle account on RCA-BMG – review.

And while the latter has many fine qualities – not least spontaneity

and freshness, which suffuses much of his cycle – the crucial

last movement comes a little too close to being unseamed. Abbado

is a master of the long span – ditto James Levine for RCA, whose

Mahler 3 is available on special order from ArkivMusic – and

that’s a most desirable skill where this vaulted structure is

concerned.

The expansive start to the first movement is one of the most

arresting introductions in all Mahler; and so it is here, but

then things start to go wrong. The music that follows – that

slow awakening, punctuated by timps and bass drum – very nearly

stalls altogether. The diffuse, rather distant recording doesn’t

help either; I wonder why Decca chose the Konzerthaus/Schauspielhaus,

which doesn’t strike me as a very grateful acoustic? Still,

the percussion is reasonably well caught. The underwhelming

brass aren’t so lucky; indeed, they sound surprisingly uneven

at times, nothing like the confident ensemble that blazes its

way through the DG DVD of Strauss’s Eine Alpensinfonie

under Kent Nagano. As for the strings, that shrill, biting passage

at 20:20 is hopelessly underpowered. Ditto the usually cathartic

final tuttis.

It doesn’t get any better, I’m afraid; the second movement is

disfigured by a woeful orchestral blend and, thanks to plodding

tempi, this miraculous little dance is leached of all its grace

and charm. In Abbado’s hands – and especially in the ‘hear-through’

readings of Gielen and Zinman – rhythms are sensitively sprung,

Mahler’s exquisite details lovingly revealed. In the scherzo

the soft-edged recording simply exacerbates the band’s lack

of precision and bite; but then Ashkenazy’s reading is hesitant

and unfocused anyway, with none of those heart-stopping epiphanies

that others find in this music. Take that ineffably beautiful

falling theme at 7:30, where Mahler’s sustained, singing line;

here it emerges as a series of ragged gasps. As for the post

horn, it’s impossibly distant, but at least the soft beats of

the bass drum add some much-needed frisson to the mix.

Try as I might, I simply cannot find any redeeming features

in this performance; the scherzo drags to a painfully protracted

close and soloist Vermillion struggles to make sail while marooned

in the doldrums. Frankly, if one were to lampoon the Mahlerian

style, this would be the way to do it – charmless, shapeless,

hopeless. Even the boys’ chorus is less uplifting than usual,

the grey start of the final movement promising more of the same.

This great span is one of Mahler’s most generous, open-hearted

creations, and in the right hands – Abbado’s especially,

but Levine is pretty special too – it should build into

a series of perorations that simply take one’s breath away.

No such luck here, though. More out of duty than devotion I

endured this spasmodic finale, mightily relieved when it was

finally over.

I cannot recall a more dispiriting, disjointed Mahler performance,

either in the concert hall or on record. Two consecutive Mahler

centenaries have prompted – and will encourage – a surge of

new releases and reissues; that said, few could be as ill-advised

as this one. Even the filler can’t save this set which, I suspect,

will soon be returned to the dusty vaults from whence it came.

Dan Morgan

|

|