Interview with Sir Mark Elder at Manchester in November 2011

by Michael Cookson.

“I’ve always assumed that the singers would be

grateful not to have to do it all in one go because many of

the roles are so taxing.” Sir Mark Elder

Part 1: Wagner and other Operas and Musicals

1.1 Opera Concert Performances and Semi-Staged Operas with

the Hallé

1.2 Concert Performances of Wagner Operas

1.3 The Situation at Opera Rara

1.4 French Grand Opera - Meyerbeer; Donizetti; Rossini; Verdi

and Wagner

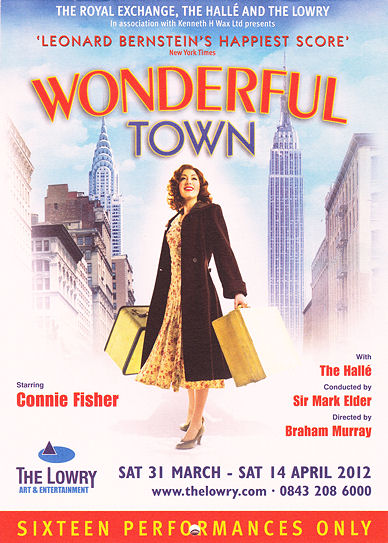

1.5 Hallé to Play Bernstein’s Wonderful Town at

Lowry Theatre, Salford

Sir Mark Elder, photo Simon Dodd

Sir Mark Elder CBE is the pre-eminent, home grown conductor

based in Britain today. It was good of Sir Mark to agree to

the interview at his Manchester apartment. I can only hazard

a guess at the constraints Sir Mark’s diary must place on his

available time. The previous evening Sir Mark had conducted

his Hallé Orchestra at Manchester’s Bridgewater Hall in a programme

of Vaughan Williams’s Symphony No. 5 and Elgar’s Cockaigne

overture with the Dvorák Wind Serenade directed by

Andrew Gourlay.

Now in his twelfth season as music director Sir Mark has had

great success in rebuilding the Hallé Orchestra’s international

reputation. From his first concert as music director in 2000

the Hallé under Sir Mark has gone from strength to strength.

The partnership achieved a double success in the 2010 Gramophone

Awards winning both the Opera and Concerto categories

with their live recording of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung

and the Elgar Violin Concerto with soloist Thomas Zehetmair.

Another success for Sir Mark and the Hallé has just been announced

with the 2011 Gramophone Award for Elgar’s The Kingdom in

the Choral category. Hallé

Catalogue

Opera is a clear passion for Sir Mark who said that he discovered

opera in the late sixties whilst still a student at Cambridge

University where he would attend productions at Covent Garden.

After university, as a protégé of Sir Edward Downes, he cut

his teeth conducting opera at the Sydney Opera House in Australia.

Later from 1979 he became music director of English National

Opera, a post he held for 14 years. Sir Mark appears regularly

in a number of international opera houses; in particular the

Royal Opera House London, the Metropolitan Opera New York, and

the Opéra National de Paris. He became the first British conductor

to conduct a new production at the Bayreuth Festival. Sir Mark’s

enthusiasm for English music is well known with each Hallé concert

season including a number of works by composers from these shores.

I cannot think of another conductor around today with a profile

as high as Sir Mark who programmes as many works by English

composers.

In recent months Sir Mark has been an integral part of the much

talked about BBC 4 flagship series Symphony presented

by Simon Russell Beale. As well as commenting eruditely on this

musical journey charting the history of the symphony Sir Mark

has been conducting the Hallé Orchestra, the Orchestra of the

Age of Enlightenment and the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

1.1 Opera Concert Performances and Semi-Staged Operas

with the Hallé

MC: After performing Wagner’s Götterdämmerung

and Die Walküre are there any future plans for more opera

concert performances by the Hallé? Or even another semi-staged

opera like Verdi’s Falstaff that you did a few years

ago?

ME: To semi-stage an opera requires considerably more

time to do than a concert performance of an opera. The operas

that we have been doing recently have been Wagnerian. We did

Götterdämmerung and Die Walküre and we may

do more Wagner in 2013. Because 2013 is his anniversary, the

bicentenary of Wagner’s birth. Yes, we did semi-stage Falstaff

some years ago now and it’s possible to do it if the orchestra

isn’t too large; so that leaves you space on the stage. Falstaff

was written for a classical orchestra whilst the Wagner scores

almost all of them are written for much larger forces; so you

just don’t have the space. And for these long operas you need

more time. The non Wagner ones are generally much shorter and

of course they are very expensive to put on at the moment. The

budgets that we are all surviving under have been cut back and

cut back. We have to be very careful how we use the little money

that we’ve got. But I hope that it will be possible to find

opportunities.

MC: So you remain hopeful?

ME: Yes, yes.

MC: But nothing has been formalised?

ME: Nothing that I am able to talk about at this stage…

what can I say!

1.2 Concert Performances of Wagner Operas

MC: I’m thinking back to the Hallé’s concert performances

of the Wagner operas. Does the concept work of dividing the

work over two nights?

ME: I think that it depends on your previous knowledge

of the work. I’ve seen the pieces for such a long time that

I’m used to the length that’s involved, the concentration and

the energy you need to listen. I thought that on both these

occasions, generally speaking, that it did work. Götterdämmerung’s

first act is so long and so demanding. The idea is that

we do the performances not too late at night so that people

have a chance to travel after it’s finished. As the performances

are concentrated into these two days it makes an interesting

visit for people from London or elsewhere in the country who

have travelled up to Manchester. It makes the travelling back

afterwards much easier.

MC: Would you ever consider doing the whole Wagner opera

on a single night?

ME: Oh sure. Sure we would consider it. But the feedback

and the actual idea seem to have captured people’s imagination

and we have the feeling that it was a success.

MC: On the other hand I feel that some people might not

have liked the idea of travelling into Manchester two nights

running for one opera. But I’m glad it was a success. Would

you continue with the idea again?

ME: Well only if it was long enough to do, such as the

whole of Tristan und Isolde, we might do it over two

nights. I don’t know. You see the orchestra here is a wonderful

orchestra but of course the stamina required to play these scores

if you haven’t done them before in one go is enormous. I think

that the orchestra felt it was helpful for their energy levels

to think. Right, I’m coming in, I’m going to play this one

act for two and a half hours and then tomorrow we are going

to do the other two acts. So it will keep them fresh. However,

some of the singers said to me that they preferred to do it

all at once, as they were up and running they preferred to finish

the race.

MC: I’m not surprised that once they are fully prepared

and actually on the stage, as soon as their voices had warmed

up and acclimatised they wanted to carry on.

ME: Yes, and that might be a good reason to do it all

in one go. I’ve always assumed that the singers would be grateful

not to have to do it all in one go because many of the roles

are so taxing.

MC: I recall reading recently where you talk at length

about there being so few Wagnerian singers around. The best

ones must be in constant demand?

ME: That’s true. There are so few around that they are

mainly booked up for years.

1.3 The Situation at Opera Rara

MC: I’d like to ask you about the situation at the record

company Opera Rara. The financing from the Peter Moores Foundation

has now stopped so how does that affect your involvement with

Opera Rara?

ME: Well the fact that I’m involved at all is because

with the death six years ago of Patric Schmid, Opera Rara is

having to reinvent itself. [Note: Patric Schmid co-founded

Opera Rara] Also the repertoire they do has always interested

me; the Italian operas particularly. Without Patric at the head

of the organisation, because he founded it, he did everything;

you actually need to replace Patric with a number of people.

You can’t have just one person. I didn’t have the time to do

everything that Patric did and I’m not a musicologist. So it

means that the whole Opera Rara organisation has to come together

and we needed to find people to fill all these different roles

and make it into a fully fledged organisation with fundraisers

for the first time in the organisation’s history. Because Peter

Moore’s great generosity kept it all going for years. He put

in hundreds of thousands a year. So it’s a huge, huge issue.

At the moment we are trying to find out whether or not we can

survive with my artistic directorship and Roger Parker the professor

of music at King’s College, London who is a Donizetti specialist,

and someone to help with the casting and two people to help

fundraise and build up the office. Now it’s a difficult time

to do it. But my impression is that there are people who would

support Opera Rara’s projects rather than supporting other different

types of music and we just have to find these people and try

to impress them and inspire them in supporting what I want do.

MC: I can sense your passion for the rare and forgotten

opera repertoire.

ME: O yeah, when they are good. The one we have just

put out on Opera Rara is Maria di Rohan one of Donizetti’s

most mature pieces. Link:

http://www.opera-rara.com/site/product.asp?section=1&cat=1&sub=1&prod=1676

MC: I’m sure that Maria di Rohan will be a new

name for many opera lovers.

ME: Yes, it will be. However, it was staged this summer

at the Buxton festival.

Sir Mark Elder at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden,

photo Laurie Lewis

1.4 French Grand Opera - Meyerbeer; Donizetti; Rossini;

Verdi and Wagner

MC: I’m very interested in French Grand Opera, especially

the early period when Paris was dominated by Meyerbeer, Halévy

and Auber. These composers exploded on the scene in Paris in

the early 1830s and were the pop stars of their day. But today

their works are rarely heard and almost never staged.

ME: Yes, it’s interesting isn’t it.

MC: I’m just thinking of those operas that achieved the

most stagings at L’Opera in Paris. Meyerbeer’s Les

Huguenots had over eleven-hundred Paris performances, then

there is his Robert le diable, Le Prophčte

and L’Africaine. There’s Halévy’s La Juive, Auber’s

La muette de Portici and Thomas’s Hamlet just

to name the most successful ones. Probably the only exception

being Rossini’s William Tell which as you know is sometimes

revived and has been recently recorded by Antonio Pappano.

ME: The equivalent nowadays Michael is the musicals of

Andrew Lloyd Webber. Where the mixture of the particular story

and the lyrics, the tunes, the way he sets the whole musical

idea, not just the songs but the bits in-between, and the lavishness,

the stage effects of the production; that is what Meyerbeer

really perfected. Meyerbeer was clever, a really astute man.

The son of a Jewish banker in Berlin he was very eclectic. Meyerbeer

learned a lot from the Italian traditions, he realised what

the Parisian public would like from his time living and working

in Italy. He had the German sense of the big scale.

MC: Meyerbeer was marvellous at marketing himself and

his music too.

ME: Absolutely brilliant. Yes, he took all his critics

out on the night before the premičres. Bought them dinner and

made sure they gave good reviews.

MC: Those must have been wonderful days for French Grand

Opera, in spite of all those rather dubious goings-on with the

claque. There was the epic, serious, often historical

scope of the libretto, the lavishness of the sets; the entrepreneurship

of Louis Véron; the extended length of the operas; the active

choruses and necessity for the inclusion of a ballet.

ME: That’s right because of the taste. And this whole

question about Opera Rara and the repertoire over the last three

hundred years is to a huge extent connected to the taste of

the country; the taste of the city sometimes; the taste of the

period. And how our taste has changed; what we enjoy. It’s very,

very difficult to make one line through it all. I have come

at that Grand Opera through Donizetti and Verdi. Verdi first

wrote Jérusalem for Paris which is a re-write of I

Lombardi; it’s a very good opera. He re-wrote Il trovatore

as Le trouvčre and changed it a bit and as you say

put in the ballet.

MC: Yes, he knew one had to have the ballet to appease

the requirements of the Paris Jockey club.

ME: And Wagner got that wrong didn’t he with Tannhäuser?

He knew he needed a ballet in the second act but he thought

he would get away with it… Les vępres siciliennes is

another one; much better performed in French than in Italian.

Don Carlos is too in my view but it’s just very difficult

to find French singers. It’s difficult to do these works in

French really beautifully. One of the first Donizetti operas

that I recorded was his last opera Dom Sébastien which

was him absolutely trying to beat Meyerbeer at his own game.

It’s a terrific opera; it’s got very, very striking scenes in

it, full of grand and memorable music. Link: http://www.opera-rara.com/

MC: Has Dom Sébastien been staged in recent years?

ME: No it hasn’t been staged. You would need a theatre

that was really passionate about doing it. I’ve just been in

Paris doing Tannhäuser and I’ve often wondered if

I ought to talk to the Paris Opera about whether or not they

would consider doing it. Because it was written for them.

MC: Was it for commercial reasons that Dom Sébastien

hasn’t been given for so long?

ME: Sometimes in the theatre world Michael it’s actually

the way pieces are staged that may make the difference between

it being a commercial success or a commercial failure. This

is where the taste aspect comes in. Robert Wilson for instance,

the American director, has had success for some years now in

Paris with the very refined, beautifully lit productions that

he likes. They don’t really go down well in London at all. In

Paris they did his Magic Flute and I conducted his Pelléas

et Mélisande some years ago at the Garnier theatre in Paris

and I don’t get it. He did a Frau ohne Schatten at the

Opéra Bastille and I’ve lasted one act. What he does is so refined

and so beautiful that it’s another form of entertainment. Paris

is the city that invented perfume and their French cooking.

This refined cultural activity is something that they have always

loved.

MC: It’s infused in their character. We are so close

to each other in proximity but British and French taste can

be so very different.

ME: Yes, that’s right... I would really like to try some

of these French Grand operas. I’ve studied Meyerbeer’s Robert

le Diable a lot and I would really like to do that. I don’t

really think it’s worth doing now if you wanted to record them

unless you do them complete. Because they have never had a chance

to be assessed complete. We know Meyerbeer cut them but I sense

from studying Robert le Diable his command of the big

forms. Because each act doesn’t have many numbers, but each

number is very broad in its construction. And if you start taking

out little bits it’s like how do you define the human body beautiful

if it’s only got one arm or one leg. It’s tricky. I think it’s

time that someone did some Meyerbeer and did it full on, one

hundred percent. But now - in a recession?

MC: Meyerbeer certainly finds it hard to get a foothold

in the repertoire today. Wagner’s anti-Semitic attacks on him

affected his reputation.

ME: There is that of course. My view is that he had everything

apart from the talent to be a great melodist. His tunes, most

of his tunes are not as good as Verdi’s.

MC: I fully agree. But in each of his most successful

operas there are two or three really fine extended scenes that

are most dramatic. That also goes for many of the other successful

grand opera composers of the day.

ME: That is absolutely true. But the ones that survive

and the ones that fall down, for our time now, don’t necessarily

equate to the ones that need to be heard. The most outstanding

example I can think of in recent times was about twenty years

ago when I did the British premičre of the opera Ermione

which is the Italian word for Hermione by Rossini.

We did two London concerts with the Orchestra of the Age of

Enlightenment. If you look into the history books Ermione

is just dismissed because it was only given two performances

because the public of the day couldn’t get it. He didn’t give

them what they were expecting, it was very unconventional and

so they were disappointed and they thought the music wasn’t

good. They booed it, it was just a disaster. But if you don’t

read all that and just get a score and study it yourself; as

I did. I became completely gripped by it and I could see the

potential to make it exciting. So we did it and everyone was

incredibly moved by the piece. We thought, how can we not know

this opera? Well a month ago the Opera Rara recording of Ermione

that my friend and colleague David Parry conducted won a Gramophone

award. The work is now absolutely established as an important

tragic Rossini opera. Glyndebourne decided to have a go at it

and did it after the performances that I did. It’s been done

a bit in Italy but this is the first really good recording and

it won a Gramophone award; it’s wonderful. Link: http://www.opera-rara.com/

Wonderful Town

1.5 Hallé to play Bernstein’s Wonderful

Town at Lowry Theatre, Salford.

MC: I’m fascinated that the Hallé is to perform Bernstein’s

Wonderful Town.

ME: Yes, for the first time we are taking the orchestra

into the pit this Easter at the Lowry Theatre at Salford. I’m

collaborating with the Royal Exchange Theatre in Wonderful

Town.

MC: Yes, the Leonard Bernstein musical that will star

Connie Fisher. But a musical, not an opera?

ME: Yes but it’s a great, great piece. This orchestra,

as you probably know, swings better than most English orchestras.

It does an enormous amount of American music at Pops concerts;

that sort of thing, like the Boston Pops Orchestra.

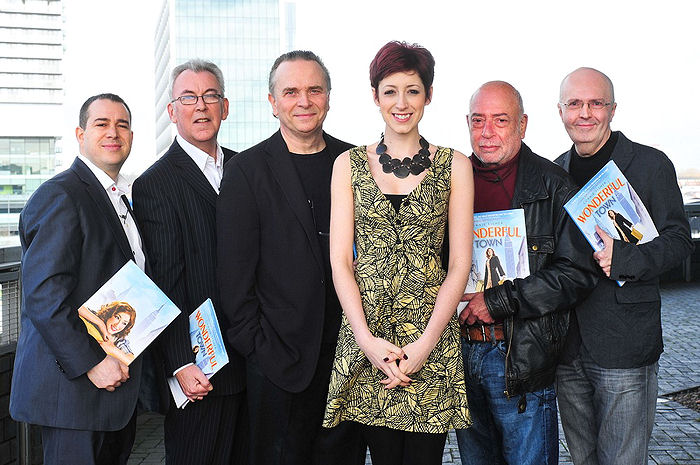

Sir Mark Elder, Connie Fisher at the Wonderful Town launch,

photo Ben Blackall.

MC: Do you really need a top ranked symphony orchestra

to play music that is normally played by a pit orchestra?

ME: Yeah, a pit orchestra absolutely. Well yes and no.

After we do the three weeks here at the Salford Lowry the whole

show is going to go on a national tour with a much smaller orchestra

conducted by a great friend of mine my assistant Jamie Burton.

It’s going to go on a national tour for three months and that

will be in a more usual format. But because we’ve got a large

pit here in Salford and I’ve wanted the Hallé to do something

different like that. And I think they will enjoy it. I’ll have

quite a good string section there and all the wind players that

you see will be from the Hallé.

MC: It should be great. I hope to report on it. I’m looking

forward to it tremendously.

ME: So the sound should be really special and we hope

to attract attention through that.

................................................

“You have to believe don’t you? You have to believe

in what you do!” Mark Elder

Part 2: English Music

2.1 Elgar Oratorios and their Debt to Parsifal

2.2 Neglect of English Music in Concert Programmes

2.3 The Relative Merits of Sir Malcolm Arnold and Sir Michael

Tippett

2.4 Sir Simon Rattle Programming English Music in Berlin

2.5 Elgar Symphonies

Sir Mark Elder, credit Simon Dodd

2.1 Elgar Oratorios and their Debt to Parsifal

MC: I can’t thank you enough for championing English

music both in the concert hall and in the recording studio.

ME: I’m the only English conductor of an English symphony

orchestra.

MC: Yet, I’ve seen a press comment about you conducting

Elgar’s The Kingdom at every opportunity; as if this

was wrong. I felt it was unwarranted and I was wondering what

you made of it?

ME: Four years ago I conducted The Kingdom for

the first time in my life on my sixtieth birthday. Two years

ago now I conducted it here again Manchester, we recorded it

and that recording won a Gramophone award as you know. Last

year I conducted it again at the Barbican. So I’ve conducted

the work three times in four years.

MC: Three times in four years doesn’t feel obsessional

to me. (ME: No) Of course once you get to know the score

it becomes easier to do the next time.

ME: Yes, because you do it better. That’s the point.

MC: All the preparation has been done.

ME: It’s like laying down a wine and not drinking it

too young. Every time I conduct it there’s more richness there,

more understanding. I know how to get the players with me to

do it more beautifully. I know what the problems are. These

oratorios of Elgar… well I’ve lived with The Dream of Gerontius

all my life. It was an A level set work when I was a school

boy. I didn’t understand it then but the music has lived with

me all my life. Whereas the music of The Kingdom and

The Apostles has not. I took ages to decide whether or

not I could do them. Now next year we are going to do The

Apostles.

MC: They are much overshadowed by Gerontius.

ME: Yes they are overshadowed by Gerontius for

reasons one can talk about if you had the time to compare them.

Basically it’s because of the narrative. The journey that happens

in Gerontius is one that everybody can immediately relate

to. It comes over very strongly. The path, the journey that

the soul makes to death and after death is a story, is a narrative

idea that everybody can relate to. The music of course is, I

think, absolutely wonderful. Some people, even dear friends

of mine, think that there are weaker moments in it. But as a

conductor I don’t know where those are.

MC: So you can’t identify those so called weaker moments?

ME: No I can’t. In Gerontius I never get to the

point where I think, ehm, he didn’t work hard enough at that

bit. No.

MC: Maybe an audience doesn’t have the concentration

and insight that the conductor has to have?

ME: That’s right, to get the organic flow in the music.

Now The Kingdom is more meditative than Gerontius.

They both have a slight amount of narrative but really the form

of the work is more narrative. And the words are taken piecemeal

from all through the Gospels; indeed some of the Old Testament

too. You have to find the line through it and that makes it

less immediately powerful for the public. But I think what he

left us with The Kingdom is a great, great work. It’s

important to remember that Wagner’s Parsifal was a huge

influence on him and he went to Bayreuth twice or was it three

times in the years after Parsifal was premičred?

MC: It’s remarkable just how many composers from all

over Europe were attracted to Bayreuth at that time. I know

that Sir Hubert Parry and Sir Charles Stanford attended Bayreuth

more than once.

ME: That’s right, that first Ring Cycle at Bayreuth in

1876 must have been an amazing event. But what’s really important

is whether people want to share this journey that I’m trying

to make with this music. The last time I did The Kingdom

it was with the London Symphony Orchestra and it was sold

out.

MC: You see a real demand from the public for this music?

ME: Yes, if you can unlock the secrets. We’ll do The

Apostles here at the Bridgwater next spring.

MC: Is this the first time?

ME: Yes we haven’t done it before. It’s been cast for

ages. We have to work two years ahead.

2.2 Neglect of English Music in Concert Programmes

MC: I’d like to ask you about the broader subject of

English music. Recently I was at a concert and they played Rachmaninov’s

First Piano Concerto. A fine work from the teenage composer

but not as melodic or memorable as his Second Concerto and

not as challenging or as dramatic as his Third Concerto.

This got me thinking how many English piano concertos would

have been just as worthy for inclusion in the concert programme.

Narrowing the field down to the Royal College of Music alone

I can think of John Ireland’s Piano Concerto; there are

also Howell’s two Piano Concertos; then the Parry Piano

Concerto and two Piano Concertos by Stanford; I’m

also thinking of the Bliss Piano Concerto and also his

Concerto for 2 Pianos. There are Sir Arthur Somervell’s

Normandy ‘Symphonic Variations’ and Highland

Concerto and also Frank Bridge’s Phantasm. All works

that are rarely played; if at all. As you know Stanford’s large

number of pupils at the Royal College wrote in most genres and

with the exception of the works from Ralph Vaughan Williams

and Holst most are totally ignored; laying forgotten. Of these

there will be many worthy works that never get a chance in the

concert hall.

ME: Of course, I understand your point. Last night we

did Elgar’s Cockaigne overture and Vaughan Williams’s

Symphony No. 5. It would have been fine by me to have

done Ireland’s Piano Concerto as well but the audience

would have been substantially smaller. [Note: John Ireland

was born in Bowdon near Altrincham just eleven or so miles away

from Manchester’s Bridgewater Hall.]

MC: Last night English music was well served by yourself

and the Hallé. I certainly acknowledge that you do more than

your fair share. But I’m concerned about getting other conductors

and orchestras to follow your lead and play more English music.

I cannot imagine countries such as Germany and France neglecting

music by their home grown composers to the extent we do in England.

ME: But then you have to have English musicians conducting.

It’s very rare for a non-British music director or non-British

conductor to really believe in a piece of English music. I’m

not saying that it doesn’t happen, it does happen all the time.

Cristian Mandeal is Romanian, he conducts the Hallé each year

and he loves Vaughan Williams. He has done some performances

of British music and I think that is very exciting. I find the

Russians like British music too. Evgeny Svetlanov who was a

great conductor took the London Symphony Chorus and English

soloists to Moscow and did The Dream of Gerontius. But

I suspect your point is slightly different; it is how can more

English works begin to be part of our repertoire? You see the

Rachmaninov First Piano Concerto that you heard is a

popular piece and people feel comfortable seeing it on a programme.

This is a brilliant virtuoso concerto by a famous virtuoso.

Rachmaninov has great appeal to the public. But of course I

understand your point that there is a lot of music that is just

as worthy. That’s one of the reasons why a few years ago I recorded

Bax’s Spring Fire with the Hallé. It’s a masterpiece

a huge orchestral piece. It’s on the CD that we brought out

titled English Spring. Details

MC: Yes it’s a splendid recording. Those Bax symphonic

poems are superb works they have all been recorded but are hardly

heard in the concert hall. You’re saying that there is nothing

to prevent other orchestras programming more English music but

there are not enough orchestras that have English music directors.

Then there is the financial side to consider also.

ME: You see when programming such works our director

of marketing at the Hallé would say that’s a lovely programme

and I’m looking forward to it already if that’s what you want

to do. But you must understand that you will have three-hundred

less people in the audience than if you did a more popular work.

Now the difficult job of planning the concert season with an

orchestra is how to balance that and it’s perfectly possible

to say, I’m going to do say for example Winter Legends by

Arnold Bax and not Beethoven’s Fourth Concerto because

we’ve all heard the Beethoven so often let’s do something different.

But then you have to recognise that not so many people will

be as confident about enjoying the concert enough to buy the

tickets. So you have to budget that concert lower. Now that’s

fine, and we do that every year, we budget it lower, but you’ve

got to know that later on down the line you have concerts that

you have to budget higher to make up for it. Do you see what

I mean? Otherwise you are going to be out of pocket.

MC: So when planning a season’s programme you cannot

let your heart rule your head.

ME: Right. It’s getting the right balance between business

and artistic vision.

MC: Just looking down a list of Stanford’s composition

pupils at the Royal College of Music I can see over thirty of

them. Some of their music is now being recorded but is still

virtually ignored in the concert hall.

ME: The fact that a lot of this music is recorded now

is great. It leads to people like yourself being passionate

about it but it also gives the planning part of the music profession

more confidence to schedule it in concert programmes. I’m the

only conductor in the world who conducts Bax’s Spring Fire;

I know because there is only one set of parts and I’ve got

them.

2.3 The Relative Merits of Sir Malcolm Arnold and Sir

Michael Tippett

MC: That’s really admirable for the cause of English

music. I just wish there were more conductors willing to venture

into this area. Maybe others will follow your lead? Recently

there was festival of music by Sir Malcolm Arnold where all

his symphonies were performed. It was held in Northampton to

celebrate the ninetieth anniversary of his birth and they used

amateur orchestras. I was wondering what your view is of Malcolm

Arnold’s music?

ME: Every few years someone says to me that I ought to

listen to this piece by Malcolm Arnold either this symphony

or this concerto whatever. I listen and it doesn’t mean anything

to me. It just doesn’t get to me.

MC: That’s interesting. The curious case of Malcolm Arnold.

Why do you think that is? Is he not serious enough? Does the

lighter nature of some of the music put you off?

ME: On the contrary. Actually he’s a very skilful composer

and the lighter pieces are very good; his sets of Dances

and the Tam O’Shanter Overture are very effective pieces.

But when he starts to write something more substantial I just

find a lot of his musical invention weak. That’s all I can say...

His music just doesn’t appeal to me. I think Michael Tippett

is a much greater composer so I would always do a work of his

rather than one of Malcolm Arnold. Nobody plays Tippett’s music

nowadays.

MC: No, his music seems very much out of fashion. He

didn’t help himself by using contemporary effects for example

in his opera New Year there was break-dancing in the

choreography and trendy ‘street talk’ of the time.

ME: It dates so quickly doesn’t it?

MC: So you have more depth to work with in Tippett than

Arnold?

ME: Yes. I think he’s a great mystic; like Vaughan Williams.

I think Michael’s music goes somewhere that very few people

actually get to. But not in all his pieces.

MC: Like many people you find his music uneven in quality?

ME: Very.

MC: Which piece of Tippett’s do you like in particular?

ME: The Midsummer Marriage is one of the greatest

English operas.

MC: I’m thinking of that wonderful set of four Ritual

Dances from The Midsummer Marriage.

ME: Yes the Dances but the whole opera which I

have done twice is a great, great piece with a poor libretto.

But then there are lots of great operas with poor librettos…

I think King Priam his second opera is a very good piece;

in a very different style. I think the Symphonies are

good; particularly Two and Four. The Piano

Concerto is marvellous and the Concerto for Double String

Orchestra too. I think the Triple Concerto is a pretty

good work but it’s hard for the public to get. I gave the first

Chicago performance of the Concerto for Double String Orchestra

with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra last year. They absolutely

loved it and it was very, very exciting to do it. I think the

first half of his career produced more lasting music. My feeling

is, although it might seem arrogant of me to say this, is that

Michael lost his way a bit as he went through the sixties and

the last part of his life. The music just doesn’t have the same

power actually, although, The Rose Lake is a fine work

and right from the end of his life. The first thing that I did

here in Manchester before I became music director of the Hallé

was his huge oratorio The Mask of Time which is a very,

very fine work. I think he manages to bring off this enormous

piece for the whole evening. The Mask of Time is about

a wide range of subjects through history; it’s a whole evening.

It’s a very different piece from the earlier oratorio A Child

of Our Time which lasts for half that time. It’s his most

popular oratorio but I’ve never responded to it. I’m not interested

in it although it’s an important work. But The Mask of Time

is a piece of vision. Now I would rather spend time working

on a great Tippett work than a work by Malcolm Arnold for example

but that’s only my taste. You have to believe don’t you? You

have to believe in what you do!

2.4 Sir Simon Rattle Programming English Music in Berlin

MC: It’s good to see that Sir Simon Rattle has got English

music in his programme with the Berlin Philharmonic this season.

(ME: Ah, good) He’s already conducted the world premičre

Jonathon Harvey’s Weltethos and Walton’s First Symphony

has been played by the orchestra. Then there’s Elgar’s First

Symphony; The Dream of Gerontius and the Enigma

Variations in there too. I did notice that Sir Simon was

only conducting Weltethos and Enigma himself.

ME: Simon has championed contemporary English music all

his life. He’s done a great deal of commissioning new works.

MC: I sense that his passion is more for introducing

new music these days rather than exploring the English late

Romantic repertoire.

ME: I think that’s right. He has done the big pieces

of Elgar and he likes them but I don’t think they are as dear

to him as they are to me. Which is fair enough. I’ve spent hours

on those Elgar symphonies. I’ve done them all over the world

and I think they need to be heard and played. The first time

it all seems a bit daunting, long and involved and you can’t

quite get it. So you need to go on playing them so people get

used to them. We went to the Bregenzer Festival in Austria this

summer where they perform opera on the lake. My friend David

Pountney runs that festival and I did two concerts there with

the Hallé. The second concert was Elgar’s Falstaff and

the First Symphony. The symphony made an enormous impression

on the public and many must have been hearing it for the first

time.

Hallé Orchestra and Sir Mark Elder, photo Joel Chester Fildes

2.5 Elgar Symphonies

MC: On the subject of Elgar I recall reading that you

think the Second Symphony is the stronger of the two.

ME: Both are very great works. I think there is greater

depth and maturity in the whole work of the Second Symphony.

I think that the slow movement of the First Symphony is

one of the greatest things that he wrote. I think that it’s

an absolutely amazing achievement, very beautiful and very moving.

But I think there are some weak moments in the two symphonies.

Like the middle of the concert overture In the South

his developments weren’t always the best bits. You have to bring

them off and not allow people to think about them. Keep on going

as Elgar did himself when he conducted. I think there are fewer

weaker moments in the Second Symphony. I find the Second

Symphony one of the greatest symphonies ever. You know that

I am doing this television series Symphony for BBC 4.

Well in the last of the four programmes I actually get to Elgar’s

Second Symphony; I do two extracts from it with the Hallé.

I think that it’s a very important work.

........................................................................

“All the time, everyday I’m thinking about how

I can present music to my audience in a way that will interest

them, keep their curiosity and draw in more people.”

Sir Mark Elder

Part 3: Attracting and Maintaining Audiences - Broadcasting

Live Performances

3.1 Making Concert Programmes Interesting

3.2 Attracting Young People to Concerts

3.3 Hallé Educational Programme

3.4 Broadcasting Live Concerts and Operas to Cinemas and

Internet Streaming.

Portrait of Sir Mark Elder with kind permission of the artist

June Mendoza

3.1 Making Concert Programmes Interesting

MC: If I may I’d like to ask you about the subject of

making concert programmes more interesting, more inviting. In

September I attended a concert at the Berlin Philharmonie with

Sir Simon conducting Mahler’s colossal Symphony No.8.

To begin the concert Sir Simon programmed two sacred works for

unaccompanied choir: Lotti’s Crucifixus and Tallis’s

Spem in alium. Two devotional scores that at first sight

in the programme might seem incongruous yet I think was a superb

contrast. (ME: So do I.) I enjoyed the way that you arranged

last night’s programme playing the Vaughan Williams Symphony

No. 5 as the opening work and positioning Elgar’s Cockaigne

overture as the concluding work. In addition you placed Dvorák’s

Wind Serenade, in effect a chamber work, in-between.

It was all most refreshing to have something presented differently

and it worked so well.

ME: Absolutely, all the time, all the time, everyday

I’m thinking about how I can present music to my audience in

a way that will interest them, keep their curiosity and draw

in more people. I’ll give you another example. A month or so

ago I came back from Paris to open the Hallé season. The main

work was The Rite of Spring by Stravinsky. But we are

doing a Beethoven cycle this season, ok. We didn’t do a Beethoven

symphony last night but we did the Third Symphony last

Saturday and next week I will do the Fourth Symphony.

So with The Rite of Spring and because it was the first

concert of the season I did the Beethoven First Symphony.

Actually it’s quite rare to start a concert with Beethoven’s

First Symphony. Then we did the Bartók Piano Concerto

No.1 played by András Schiff which nobody knows and it’s

almost never done because it’s very hard. Then after the interval

my first flute played Debussy’s Syrinx which is just

a little piece for solo flute; as you know. But she was playing

off-stage whilst the whole orchestra was on stage with the lights

dimmed waiting to play The Rite of Spring. So this whole

crowded auditorium was completely still listening to one flute

player. Then when she had finished we brought the lights up.

Everybody applauded her, she came on stage, joined the orchestra

and we began The Rite of Spring; which starts with one

bassoon and all the other instruments gradually join in. So

Syrinx, as Simon did in your Berlin concert with the

Tallis Spem in alium, served as a lead-in, like luring

your ear into The Rite of Spring.

MC: Yes, the principal works so well.

ME: Oh yeah. We did it a few nights later in Leeds and

for me it was even more effective because of the smaller hall.

Everyone was captivated saying where is this sound coming from?

They didn’t know where the flautist was… Then we did our Mahler

Eight in May 2010 at the Bridgewater Hall. The idea in

our Mahler cycle was to precede each symphony with a new commission;

to have a world premičre. I was very concerned thinking what

can one do before Mahler Eight? In the end I decided

the best thing to do would be to get Olivier Latry the organist

from Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris to come over because there’s

a big organ part in Mahler Eight and I wanted him to

play it. But Olivier refused saying he didn’t have the time

to get to know the Bridgewater Hall organ. But before we played

the Eight Symphony Olivier improvised on the plainsong

melody that is the first movement of Mahler Eight, Veni

Creator Spiritus. It was amazing, he just improvised. He

played the tune and just started improvising and Olivier is

so good at that. It was a whole event in itself and it took

twenty minutes. It seems to do something to attune ones ears.

So those are the sort of things that I’m trying to think about.

Simon and I are very close friends and we’ve talked about all

this for thirty years. You see I started at the London Coliseum

as Simon started in Birmingham.

3.2 Attracting Young People to Concerts

MC: At last night’s concert with the Hallé from the stage

you introduced four groups of children and teenagers from schools

in the Greater Manchester area. Many of whom might have been

attending a classical music concert for the first time. It’s

a great initiative and it’s so important to be introducing young

people to classical music; our audience of the future. Last

May I recall attending a Munich Philharmonic Jugendkonzert

a youth concert in Munich. It was a full house and maybe sixty

to seventy percent of the audience were young people in their

school groups. The organisers didn’t compromise giving the same

programme as the previous night for a predominantly adult audience.

The programme was Dutilleux’s Métaboles; Kodály’s Dances

of Galánta; Stravinsky’s The Firebird as well as

the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto. Really the only concession

was engaging a popular children’s presenter from German television

who bounced about the stage energetically with a microphone

introducing the works and joking with several of the orchestral

players to an amused audience. The young people loved the concert

and they cheered and cheered. I’m not one of those who think

that people at around the age of forty suddenly put down their

Springsteen and U2 discs and move over to classical music. You

see I’m concerned for the audience of the future.

ME: So am I; desperately so… At that concert that I mentioned

to you earlier, my opening concert of the season with The

Rite of Spring preceded by the Debussy, we had five hundred

students all sitting around the orchestra in the choir stalls

and in the front row of the stalls. Somehow that programme had

got through to their imagination. We only charged three pounds

but the point is that they came. We have to hope that they come

back again and won’t find it stuffy. That’s why I stopped wearing

tails. (MC: But you still look appropriate) Yes, I agree.

Hallé Orchestra and Sir Mark Elder at the Bridgewater Hall,

credit Halle collection

3.3 Hallé Educational Programme

MC: Please tell me about the work that the Hallé does

in the field of music education.

ME: Our educational work Michael if you don’t know about

the range of it you should seriously think about speaking to

our education director Steve Pickett who was a bassoonist like

I was. He’s a brilliant, brilliant man, a composer himself who

writes music for kids and the orchestra. The work that we do

nationally I don’t think we could do more. Of course we never

have to be complacent, we have to go on trying to be better

at what we do and understand more what will unlock a child’s

creativity. What we do in this area is absolutely phenomenal.

It’s not preaching to children, I don’t believe in that, I believe

in example and by showing children how they can create music

themselves that, however timidly, they can actually have the

power to create music themselves. (MC: I agree children

love to make music) I know, I know and they love to dance too.

They all want to dance. If you can combine their sense of humour

with their physical movement and their aural imagination and

let them understand that you don’t have to have a university

degree to do this you can do it just as you are. But you need

good people to lead it and Steve Pickett is a great leader.

My experience in working in Birmingham as well as London, but

especially in Birmingham with the CBSO and now here in Manchester

with the Hallé is that these two orchestras are full of people

who if you give them the right lead-time and you say what you

want, people who in the orchestra might seem quite shy or quiet

or routinely doing their job, put them in front of a group of

kids and they became a different person.

MC: You certainly have some players at the Hallé who

are talented communicators. Earlier this year your horn player

Tim Redmond gave a really confident pre-concert talk, very impressive

and I’m sure that he’s one of many who can do that.

ME: Oh yeah, there are lots more. Tom has a great ability

to present. He introduces some of our family and school concerts;

he’s wonderful at it.

MC: It’s certainly heartening to see a younger audience

and last night many of the youngsters seemed to be having a

good time.

ME: Yes, that’s the main thing. That the young people

don’t feel too restricted. I think that the main problem is

not to say, don’t move, don’t cough, don’t look around or you’ll

kill it.

MC: I remember interviewing Andrew Manze in Munich last

year. He expressed a view that young people might be put off

attending classical music concerts saying, similar things to

you. That the concert experience might appear too conventional,

that you might have to dress in a certain way, that you have

to sit still and don’t talk to your friends, that you have to

clap in the right places all restrictions that can be off-putting.

[Note: Andrew Manze conducted the Hallé in three concerts

in December 2011.]

ME: Young people should dress how they feel most comfortable

with. You don’t want young people to feel that there is a sense

of stuffy formality; an old fashioned formality that’s different

from concentrated listening. Children listen in different ways.

I think that a couple of them may have dozed off last night.

I don’t care about that; it means they were relaxed.

MC: I believe that typically young people have such an

open minded attitude to various types of music that are played

at classical concerts. Looking back at that Jugendkonzert

in Munich, in my view they don’t really differentiate between

the contemporary music of Dutilleux and the traditional music

of Mendelssohn. Maybe they lack the prejudices that older audience

members can develop.

ME: You’re right. You’re absolutely right. I’ll never

forget some years ago I went and worked with a youth orchestra

in Australia. We did an enormous amount of music with them.

I remember doing an American programme. We did Gershwin’s An

American in Paris which is great, immediate, fun music.

I did Charles Ives as well; two pieces from his Holidays

Symphony which are very complicated and very difficult to

understand. I did Washington's Birthday and The Fourth

of July which are movements representing different seasons

of the year. They are brilliant pieces and those two are the

ones that I have done the most often. So I came in one morning

and said to the orchestra “Right we are going to do the Gershwin

now” and the youth orchestra said “Ok, Gershwin that’s

fine.” Then I said to the youth orchestra “Right now

we’ll do the Charles Ives” and the youth orchestra said

“Ok, Charles Ives that’s fine.” Now when I was in America

with the renowned Cleveland Orchestra I said “Now we’ll do

the Charles Ives” and they said “Why are we doing this

stuff maestro?”

MC: And Charles Ives is one of their own composers; born

and bred in the USA.

ME: I know. And these Australian kids were completely

unfazed. They saw it as difficult, they worked at it and they

played it beautifully. But what was noticeable was how they

accepted the music without prejudice. That’s what I believe

in, trying to get people to throw away their prejudices and

not to have fear. We had a marvellous example on Saturday night

when we played Harmonium by John Adams a composition

for chorus and orchestra. It was written for the conductor Edo

de Waart and the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, oh, some

thirty years ago now. It’s a setting of three poems by John

Donne and Emily Dickinson and it lasts just over half an hour.

It’s very hard for the chorus. It’s the rhythms that are difficult

to get. We’ve never done it before at the Hallé and I’ve always

wanted to. We followed Harmonium with Beethoven’s Eroica

which was a fantastic piece of programming because everyone

was thinking what the Eroica would be like after that.

Now there are friends of mine who I know well and support the

Hallé who come to the concerts. I know this because they told

me afterwards. They sat down for the concert and said “All

right darling are you ready for this? We’re not going to like

this one. Let’s wait for the Eroica we’ll enjoy that.” Well

they came to me afterwards and said they were completely bowled

over by the John Adams. After eleven years of working with the

Hallé I hope that people will start to understand that I’m not

trying to force-feed them like goose-liver. I’m not saying this

will be good for you, come on enjoy it. I’m choosing pieces

that I know and that I hope people will respond to, even though

they don’t know them. Last Saturday for the John Adams we had

a most fantastic response from the audience.

MC: I can understand the attraction in programming the

John Adams an exciting rarely heard work combined with the Beethoven

a staple of the repertoire that will be a familiar and comforting

score to most people. The work you don’t know makes you listen

more intently, makes you concentrate, attunes your ear for what

is to come next. Rather like refreshing the palate with a sorbet

in preparation for the main course to come.

ME: I couldn’t agree more.

3.4 Broadcasting Live Concerts and Operas to Cinemas and

Internet Streaming.

MC: Only a few days ago at the cinema with a group of

friends I saw a transmission of you conducting Francesco Cilea’s

opera Adriana Lecouvreur from Covent Garden featuring

Angela Gheorghiu and Jonas Kaufman. Prior to that at the cinema

I saw Verdi’s Macbeth broadcast live from Covent Garden

conducted by Pappano. The New York Metropolitan Opera broadcast

their performances live to cinemas and theatres around the world.

I believe this is becoming an increasingly important source

of income for them. Then there is the Berlin Philharmonic’s

excellent Digital Concert Hall on which I’ve watched

webcasts of live concerts on the internet several times. They

also have interviews and reports and this media project forms

part of the orchestra’s education programme; which is a great

way of reaching out to young people in schools. I was wondering

if the Hallé had considered streaming their concerts live?

ME: I think that it would be a wonderful thing for us

to do. But you have to understand that each year we have to

raise our money just to survive. When I became music director

eleven years ago I said that I wouldn’t come until the finances

were sorted out. We’re just on the edge now of tightening our

belts really quite considerably. We just hope our audiences

keep coming because in times of economic recession people need

the spiritual content of their lives to be really engaged in

many different ways. People need music and performance so we

are hoping that the public will still support us but that sort

of initiative would cost us an incredible amount of finance

to start up. But you are right we should think about it. We

should consider whether or not as the years go by it becomes

more crucial for getting the orchestra’s quality known all over

Europe.

MC: I believe the Hallé’s international reputation as

one of the world’s oldest orchestras and their associations

with Beecham; Sargent and Barbirolli make the Hallé an excellent

brand name. There must also be considerable advantages for being

the first British Orchestra to do it.

ME: Absolutely. People know the Hallé name without knowing

it was the name of a person; our founder Sir Charles Hallé.

MC: So you would consider getting involved with media

streaming. But now is not the right time owing to the economic

climate?

ME: Yes. I’m not sure that now is the time unless we

could find sponsorship. Really we need sponsorship all the time

in order to pay our wages, in order to keep the orchestra alive.

When people who invest money all over the world are not getting

the returns from their investment they don’t have the slack

to give us the funding. [Note: Interestingly, one of

the Hallé’s major sponsors is Siemens a leading global technology

services company.]

MC: I could tell from your short announcement on the

stage before last night’s concert how much you value your sponsors

at the Hallé.

ME: We are doing really well in attracting good sponsors.

I think we are doing much better than many of our colleagues.

I entertained three of our major sponsors the other night just

to thank them and to say how important they are to us for giving

substantial amounts of funding. We’re appreciative of the local

councils too; many of whom were there last night in the audience

at the Bridgewater Hall. It’s important that they all come because

it’s a public manifestation of the support given to us by all

these towns around Manchester… But it’s a tricky time to put

it mildly.

[Note: Currently Sir Mark’s delightful semi-staged performance

of Humperdinck’s opera Hansel and Gretel (abridged version)

with the Berlin Philharmonic from 2006 at the Berlin Philharmonie

is available to watch for free. Highlights from the performance

can be seen in a trailer on their Digital Concert Hall.

I just loved the superb performance from soprano Michaela Kaune

as Gretel. Link: http://www.digitalconcerthall.com]

Michael Cookson