|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

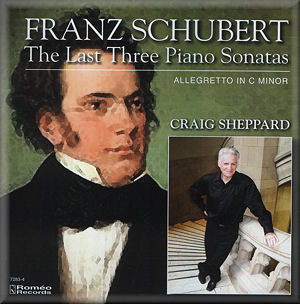

Franz SCHUBERT (1797-1828)

The Last Three Piano Sonatas

Sonata in C minor, D958 [31:12]

Sonata in A major, D959 [39:54]

Sonata in B flat major, D960 [47:12]

Allegretto in C minor, D915 [5:15]

Craig Sheppard (piano)

Craig Sheppard (piano)

rec. live, 5 May 2010, Meany Theater, Seattle, USA

ROMÉO RECORDS 7283-4 [71:06 + 47:12]

ROMÉO RECORDS 7283-4 [71:06 + 47:12]

|

|

|

Some time ago I had the good fortune to review

Craig Sheppard’s splendid cycle of the Beethoven piano sonatas.

Since then, some more of his recordings have been favourably

received here by colleagues, all of them, like the Beethoven

sonatas, recorded live in recital at the Meany Theater in Seattle.

I so admired Sheppard’s Beethoven that when the chance presented

itself to review these performances of the last three Schubert

piano sonatas I needed no second bidding.

These sonatas were all written in fairly quick succession in

the last few months of Schubert’s life - between May and September

1828. To produce three such substantial masterpieces in such

a short period of time is impressive enough as an achievement.

But if you add in firstly the fact that he was mortally ill

– he would be dead by mid-November – and, secondly, that in

the last year of his life he produced a whole succession of

other major works, including the String Quintet, the songs subsequently

published as Schwanengesang, and the Mass in E flat then

one can only marvel at his industry and invention.

The sonatas in question form, by pretty common consent, the

pinnacle of Schubert’s portfolio of solo piano compositions.

Indeed, they are among the peaks of the piano repertoire as

a whole and, like the Ninth Symphony, suggest ways in which

Schubert might have advanced the genre still further, not least

in terms of expansiveness, had he lived longer. One important

thing about them is that, notwithstanding the fact that they

were composed not long before Schubert’s death, they are not,

I believe, in any sense valedictory and woe betide any pianist

who treats them as such and attempts to wrap the music in an

autumnal cloak of farewell or regret. Happily, Craig Sheppard

is far too intelligent and perceptive an artist to fall into

that particular trap.

Sheppard’s Beethoven sonata recordings were issued under the

title Beethoven: A Journey. I was reminded of

that listening to these Schubert performances because hearing

them as a series – and knowing that this is how they were presented

to the audience in Seattle – allows one to appreciate how the

music in each tends to feed off the others – a point that the

pianist makes in his very good booklet note.

It seems to me that Sheppard has the full measure of these scores.

He is excellent in the turbulent passages that feature particularly

in D958 – but also in the other two works – and in such sections

one appreciates the physical strength of his technique – and

that he never forces the tone of his Hamburg Steinway piano.

Rhythms are unfailingly executed crisply and accurately but,

crucially, Sheppard is a discerning master of rubato. Schubert’s

music so often requires just a little ‘give’ to make its expressive

point, though this is down to the pianist’s intuition since

it’s not written in the score. Sheppard consistently gets this

aspect just right.

It’s the heavenly lyricism of Schubert’s late music that gives

it such appeal. Mr Sheppard never overdoes the lyricism, making

it maudlin; instead he lets the music breathe and sing, allowing

it to unfold naturally. Thus, the serene theme of the Adagio

movement in D958 is perfectly enunciated, with every chord or

single note beautifully and thoughtfully weighted. In this movement

Sheppard’s playing has great poise yet the occasional passages

of more robust music are strongly projected.

The Andantino of D959 is a wonderful creation. Craig Sheppard

refers to the “forlornness” of this music and this is how it

comes across in his hands. The simplicity of his playing at

the start allows the writing to speak most effectively. There

is a strong and dramatic central section (3:08–5:00), which

is projected powerfully. It provides a fine contrast with the

preceding, withdrawn episode and when the subdued music returns

for the closing section of the movement the fact that it follows

this turbulent central passage gives the slow passages an added

sadness. The finale of D959 is Schubert at his most winning

and I really admired the lyrical grace that Sheppard brings

to this music. His playing is full of light and shade, ensuring

that his reading is a conspicuous success. Earlier, he’d been

equally successful with the seemingly endless tarantella that

forms the finale of D958. It seems to me that he judges the

pacing here to perfection, giving the music sufficient space

that it doesn’t sound unduly rushed yet, at the same time, imparting

plenty of energy and momentum.

The performance of D960 is masterly. In the extended opening

movement - 19:13 here – Sheppard is suitably reflective yet

his pacing is just right – a consistent feature of all these

performances – and so the music isn’t allowed to dawdle. I thought

this was a wise and completely convincing reading of this heavenly

movement. The Andante sostenuto that follows is otherworldly;

time seems to be suspended in a good performance and this is

a very good performance. Sheppard distils great atmosphere

– surely a benefit of live recording - and displays expert control

and a great feeling for the music. When, at 5:58, the opening

material is reprised, his subtle touch is very special. I relished

the delicacy of his fingering in the third movement while his

description of the finale as “nonchalant and elegant” is highly

appropriate. I’d hesitate to call his playing of it nonchalant

for fear that might imply a superficiality, which certainly

is not the case, though the playing is relaxed. But I’ll readily

describe his pianism in this mainly genial movement as elegant.

The little C minor Allegretto is a good and thoughtful choice

as an encore.

Textually, the performances are based on Martino Tirimo’s Wiener

Urtext edition as well as the Henle and Peters

editions. All repeats are observed.

The performances were given before a live audience but I should

reassure readers that this audience, unlike some I have endured

recently at concerts, is commendably silent and attentive; one

senses that Sheppard held them in the palm of his hand and willed

them to focus on Schubert. Even when listening through headphones

I couldn’t detect any extraneous noises and there is a most

welcome absence of coughs. Those for whom it is an issue ought

to note that there is applause at the end of each work – and

it’s quite vociferous – but I don’t find that a problem.

These are exceptionally fine and satisfying Schubert performances,

which I have enjoyed greatly – and savoured. Sheppard is a perceptive

and intelligent guide to these masterpieces and his playing

and interpretations bespeak a deeply musical and thoughtful

approach. I hope that others will enjoy these discs as much

as I have done. Like his Beethoven sonatas, these are performances

to live with. I see from the booklet that Sheppard’s recording

of the complete solo piano music of Brahms is in the offing,

again drawn from live recitals in Seattle. That is eagerly awaited.

John Quinn

See also review by Melinda

Bargreen

|

|