|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound

Samples & Downloads |

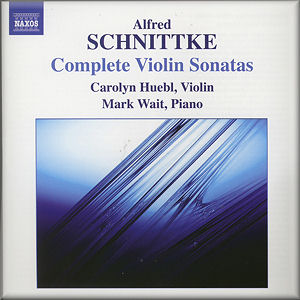

Alfred SCHNITTKE (1934-1998)

Complete Violin Sonatas

Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 1 (1963) [17:01]

Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 2 Quasi una Sonata (1968/1987)

[22:37]

Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 3 (1994) [14:51]

Sonata 1955 for Violin and Piano [14:51]

Carolyn Huebl (violin); Mark Wait (piano)

Carolyn Huebl (violin); Mark Wait (piano)

rec.1-4 June and 25-26 September, 2009, Ingram Hall, Blair School

of Music, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, USA. DDD

NAXOS 8.570978 [69:20]

NAXOS 8.570978 [69:20]

|

|

|

Schnittke's intensity, focus and inward-directed heat are ideally

suited to chamber music. Concentration, minimal consonance,

the timbres of individual instruments together with their textures

when sounded harmonically create a fertile world. There the

wry and self-confident Russian melodies that Schnittke introduces,

almost behind your back, can grow, strengthen and affect you.

Carolyn Huebl and Mark Wait, both from Vanderbilt University,

Nashville, here present all three of the composer's numbered

sonatas for violin and piano along with the earliest one from

1955. They have the characteristics of great reflection, tightness,

economy, though of a restrained and bare lyricism; of variety

and a mix of moods from the sombre to the almost jaunty and

jazzily lighthearted (the fourth movement of No. 1 [tr.4], for

example). Indeed, together with the pair's extreme technical

yet unobtrusive virtuosity, this faculty of being at home in

all Schnittke's many idioms is one of this excellent CD's strongest

points.

Equally remarkable is the extent to which Huebl throws herself

into the essence of Schnittke's string writing. Almost all of

his violin sonata writing was directly inspired by the work

- and hence the style - of Mark Lubotsky and Gidon Kremer with

their acerbic and understated tautness. To Wait's unretiring

yet sensitive pianism, Huebl brings an equally demonstrative

certainty. She never over-layers Schnittke's sonorities; they

are designed to be as spare in sound as his themes are meant

to prick rather than caress.

The Sonata No. 1 dates from 1963; it was in the following year

that Lubotsky gave the première. It makes use of serial techniques

and is generally springily experimental. Significant among its

characteristics - and equally well brought out by these two

fine soloists - is the relationship between piano and violin:

prompting, antagonising, supporting, echoing and so on. Huebl

and Wait explore these seamlessly and add to the momentum of

the sonata greatly by respecting Schnittke's conception of the

duality of these two instruments.

Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 2 Quasi una Sonata was

written just five years later, in 1968. The longest single work

on the CD at nearly 23 minutes, it's one of the composer's best

well-known and most often performed pieces with much more angularity

- anger even - than the others here. Yet, again, Huebl and Wait

have rightly preferred to accentuate the music's essence over

its surface. There are the glissandi, mordent harmonics

and wistful rhythmic ambiguities - all characteristic of Schnittke.

We also hear the gestures that may or may not be quotations

- they're certainly evocative - and the dissonant intervals

and repetitive chords - famously those for piano toward the

end of the piece. The players here are full of life, not labour:

very pleasing performances. They evoke the emotion, they don't

'demonstrate' it.

Lubotsky's and Schnittke's collaboration was renewed with the

Third Sonata, which dates from thirty years later. It’s more

spare and darker still. The two players here also capture Schnittke's

austerity though again without overplaying it. Schnittke - paradoxically

- more implies than exposes such sparseness with regard to thematic

development and instrumental sound. In keeping with what we

know of Schnittke's health at this time - his two strokes in

the 1980s were of major concern - there is little real joy or

exuberance for all the music's insistence and confidence. Both

Huebl and Wait, though the former in particular, have an expert

and effective tread when conveying something balanced finely

between resignation and regret. This can be heard in the halting

fourth movement, for example [tr. 9]. This is tellingly marked

as senza tempo, which literally means that there is no

tempo marking; but also suggests time running out.

The Sonata 1955 for Violin and Piano also lasts just

under 15 minutes but is from a different world, written forty

years earlier. In places it could be by one of the English pastororalists

of that generation. There is even a passage sounding like a

Scottish jig near the start. The challenge for Huebl and Wait

was not to treat it as an immature or incomplete piece. They

succeed very well. Each aspect of musical interest - instrumental

articulations, rhythmic particularities, cross-references -

is given its due weight. This is Schnittke, but not the one

we first think of; perhaps that's why it's placed at the end

of the recital.

There is a handful of recordings of these four works individually.

But none in the current catalogue which nicely groups all three

as this one does. That alone makes it a good choice. The acoustic

is clean and close. The notes with the booklet are illuminating.

All in all a sympathetic, revealing and enduring set of performances

that can only enhance Schnittke's reputation. Don't hesitate.

Mark Sealey

|

|