|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS |

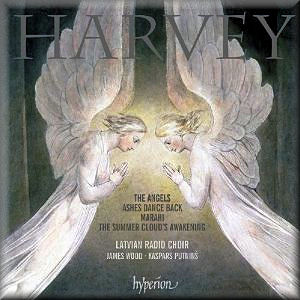

Jonathan HARVEY

(b. 1939)

The Angels for unaccompanied choir (1994) [5.03]

Ashes Dance Back for choir and electronics (1997) [17.25]

Marahi for unaccompanied choir (1999) [10.26]

The Summer’s Cloud’s awakening for choir, flute,

cello and electronics (2001) [30.53]

Jonathan Harvey (electronics); Clive Williamson (synthesiser); Ilona

Meija (flute); Arne Deforce (cello)

Jonathan Harvey (electronics); Clive Williamson (synthesiser); Ilona

Meija (flute); Arne Deforce (cello)

Latvian Radio Choir/Kaspars Putnins (The Angels), James Wood

rec. 19 April 2005, St. Saviour’s Church, Riga (The Angels);

live, St. John’s Church, Riga, 1 November 2008

HYPERION CDA67835 [63.43]

HYPERION CDA67835 [63.43]

|

|

|

The archetypal Jonathan Harvey piece mixes voices with electronics,

and that is not surprising. He was, after all, a choirboy at

the long defunct St. Michael’s Tenbury Wells. His own

son was in the choir at Winchester Cathedral. It was for his

son’s voice that he wrote ‘Motuos Plango’

in 1980 employing the great tolling bell of Winchester Cathedral

and using computer manipulation techniques. Even, quite often

performed anthems like ‘I Love the Lord’ of 1976

and ‘Come Holy Ghost’ from 1984 have such a distinctively

dense sound using wave formations, constant repetition of phrases

and thick tonal clusters that you feel that the a capella

voices have been treated with an old fashioned ring modulator.

It’s not surprising then that this new disc by the superb

Latvian Radio Choir should include two works for choir and electronics.

It starts more modestly with Harvey’s commission for the

King’s Carol Service of 1994 The Angels

also recorded back in 1995 on excellent ASV disc by The Joyful

Company of Singers (CD DCA 917).

Angels and mysticism are a sort of Harvey ‘thing’

one might say. Here with a text by his late friend Bishop John

Taylor he also uses a wordless choir which provides harmonic

support for a limpid melody shared between the other voices,

now in unison, now in canon. A line or two of Taylor’s

verse sums up the composer’s intentions “Their melody

strides not from bar to bar/but like a painting, hangs there

entire/one chord of limitless communication”. It’s

worth following the beautiful text whilst listening, as it can

sometimes get lost in the thick miasmic texture.

Jonathan Harvey has the ability to draw pre-eminent parts from

several religions or sects and channel these both musically

and spiritually. We can hear this in the Anglican tradition,

as in the anthems mentioned above, the Roman Catholicism of

his massive ‘Madonna of Winter and Spring’ of 1986

and Buddhism, which has always fascinated him. We find quite

abhorrent images on our TV screens of Buddhist monks burning

themselves to death but there is an element in Buddhism, of

giving ourselves back to the elements from which we emerged.

These elements play a major role in the next work, Ashes

Dance Back. Michael Downes’ excellent enclosed

notes tell us that the work “realizes the idea of the

‘self’ - represented metaphorically by the choir

- to the elements of wind, fire and water”. He goes on

later: “Harvey processed sounds of wind, fire and water

through a computer analysis of choral sounds producing a recording

that blends almost seamlessly with the sound and creates the

illusion that the elements themselves are singing.” From

time to time the ‘elemental’ sound is clearly audible

and at the others just fragments of the text. The Indian poet

Rumi is used in a beautiful translation by poet Andrew Harvey.

I quote “ I burn away: laugh; my ashes are alive!/I die

a thousand times/my ashes dance back/A thousand new faces”.

It is an emotional and spiritual exercise listening to this

work as it often is with Harvey but the journey is certainly

worthwhile.

We are also told that Ashes Dance Back, although continuous,

can be heard to be in three movements. For this forlorn listener

Hyperion might have been more helpful and tracked the work accordingly.

Had the done so the structure, which is difficult to grasp if

it exists at all, might then have been more clearly elucidated.

Although Marahi is only ten minutes in duration,

it has the longest text (all texts are given clearly and translated).

It is in Latin, Sanskrit with spoken sections in English. Texts

in honour of the Virgin and of the Buddha are inter-mixed very

directly. These encapsulate Harvey’s beliefs and background.

At one point the composer asks the voices to make animal noises.

These are performed here most successfully and believably. These

are included because Harvey’s wants to “suggest

the interdependency of different acts of creation”. The

whole work attempts to demonstrate “the continuity between

Christian and Buddhist beliefs”. The performance is striking

although the spoke English is not always clear.

The last work The Summer Cloud’s Awakening

is also the longest. To the choir and the electronics Harvey

adds a flute and a cello. This work has a very short text: two

in fact by Buddha Shakyamuni. It is one of his most extraordinary

scores and reveals a world of stasis and spiritual depth almost

beyond the experience of western religious comprehension. It

was composed for James Wood. In addition to the Buddhist text

sung in the English - given in translation in the booklet -

there are also musical quotes from Wagner’s ‘Tristan

und Isolde’. The famous chord drifts periodically across

the texture as well as other motifs. The music is not all mystery:

there are some faster and more ‘focused’ passages.

These ideas were to build into his 2006 opera ‘Wagner

Dream’. In these works there is a fascination with human

suffering brought about by human desire. To explain the music

would be ridiculous. You simple must buy the disc to draw your

own conclusions. You will either consider it a masterwork or

crass and pretentious.

I’m not sure why Hyperion has taken three years to get

this disc onto the market but it has been worth it. There are

some significant and fascinating pieces here. The recording

is ideal with balance and engineering of demonstration class.

The performances committed, stunning and seemingly flawless.

Well worth investing in.

Gary Higginson

|

|