|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Chandos downloads may be obtained from the ClassicalShop

|

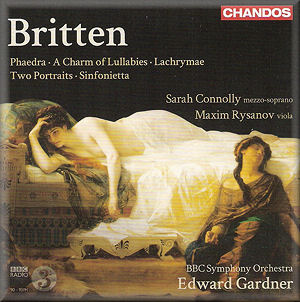

Benjamin BRITTEN (1913-1976)

Phaedra, op. 93 (1975) [15:00]

A Charm of Lullabies, op. 41 (1947, arr. C. Matthews 1990)

[12:16]

Lachrymae, op. 48a (1950, rev. 1976) [15:32]

Two Portraits (1930) [15:09]

Sinfonietta, op. 1 (1932, rev. 1937) [14:45]

Sarah Connolly (mezzo: Phaedra), Maxim Rysanov (viola: Lachrymae,

Portraits)

Sarah Connolly (mezzo: Phaedra), Maxim Rysanov (viola: Lachrymae,

Portraits)

BBC Symphony Orchestra/Edward Gardner

rec. Studio 1, Maida Vale Studios, London, 23-25 September 2010.

DDD

CHANDOS CHAN 10671 [73:18]

CHANDOS CHAN 10671 [73:18]

|

|

|

Phaedra is all concentrated tension: stark, sepulchral,

unremitting. You don’t get any perspective on her other than

her own withering self condemnation. You experience with her

that torment and feel the tragedy.

Sarah Connolly finely colours the characterization, able to

invest the singing simply of a name with eloquent meaning. Her

husband Theseus is coloured with loathing, his son Hippolytus,

her forbidden love, addressed with both desire, a covert whisper

‘I love you’, and remorse.

Edward Gardner’s handling of the orchestration graphically catches

all the resonances of this passion, especially the two great

ascents of divided strings that we learn, after the first, mark

the infusion of poison Phaedra has taken. I compared the recording

made in 1977 by the first performers of the work, Janet Baker

and the English Chamber Orchestra/Steuart Bedford (Decca 4256662).

Baker has more fiery intensity as well as sadness. Her central

recitative is colder, more stony while Bedford’s closing Adagio

is more markedly a laborious death march. Connolly brings for

the listener an equally involving uncompromising and unpitying

analysis of her state laid bare with great clarity. Her central

recitative (tr. 1 6:20), however, is warmer and Gardner’s closing

Adagio (9:19) is a smoother infusion of poison, rather

than the celebration of Phaedra’s declaration of atonement through

sacrifice. Bedford brings more tension, Gardner reveals more

detail of layering and cross-reference.

The cycle for mezzo and piano, A Charm of Lullabies, is

here presented in Colin Matthews’ arrangement for mezzo and

orchestra. ‘A cradle song’ begins with the accompaniment now

an introduction by strings. This sets a mood of deceptively

gentle contemplation belied by the uneasy flutes’ emphasis of

the infant’s ‘cunning wiles’, climax of nightmare and loss of

innocence. In ‘The Highland Balou’ balmy flutes provide a serenely

regal quality which lightens the snap of the backing rhythms.

This also allows Sarah Connolly to offer a lullaby of contentment.

In ‘Sephestia’s Lullaby’ it’s the oboe that signals foreboding

before Connolly brings a sullen chorus and hyperactive verses.

‘A charm’, on the other hand, proves to be more of a curse,

delighting in nightmare pictures of violence. After this the

oboe introduces the melody of ‘The Nurse’s Song’, an archetypically

loving lullaby, with Connolly wholly maternal, vividly conveying

wonder and gratitude mixed with anxiety. This is aided by warm

touches of horn to effect a haunting and positive close. Matthews’

orchestration is sensitive and enhancing while Connolly’s presence

well differentiates the highly varied nurse figures.

Lachrymae (tr. 7), subtitled ‘Reflections on a

song of Dowland’, is in effect variations on ‘If my complaints

could passions move’. That opening line is all that’s heard

in the introduction, a throbbing miasma of strings around viola

solo meditation. The entire theme isn’t heard until the end

as a procession on string bass (11:43). There the soloist adds

to the tension through tremolando semiquavers and a gradually

increasing dynamic until he takes over the tune in impassioned

expression. In the meantime there have been memorable reflections,

such as the second (3:07) where the viola’s pizzicato

study of the theme opening is punctuated by rapt, very soft

string chords scored for 11 parts. The third reflection (4:35)

presents a little more of the theme in sheeny high strings punctuated

by viola arabesques, yet both grow more animated, to emotive

and moving effect in this performance. The sixth reflection

(7:58) has the soloist offering a morose soliloquy quoting the

actual Dowland Lachrymae song, ‘Flow my tears’. The seventh

(8:46) is a suave and delicate waltz. The ninth (10:50) is a

stunning, icy panorama of falling strings while the viola remains

static. Maxim Rysanov and Gardner are alert and sensitive to

all these changes of mood and create a gripping account.

The first of Two Portraits (tr.8), of school-friend David Layton,

is based on a rising six-note figure. The writing for strings

sometimes flows with this and sometimes energetically tumbles

around it. A slower, more ardent version of the motif in the

cellos from 1:56 suggests an inherent sensitivity in David.

A later introduction by the violas (5:41), is soon joined by

the violins. This has a more expansive, musing aftermath and

it’s in this more reflective cast that a solo viola closes the

piece. The second Portrait (tr. 9) is of Britten himself and

spotlights the solo viola, his own string instrument. Based

on an opening phrase of eight notes, this is a more lyrical

setting. Understated at first, you mightn’t recognize a melody

until the muted violins shortly take it up and the soloist adds

a reflective commentary. If the first portrait offers a foretaste

of the angst of the Bridge Variations, the second glimpses

the haunting lyricism of the Serenade. Particularly attractive

is its becalmed final statement sinking to a dusk of pianissimo

double-basses.

Gardner’s account of the Sinfonietta is characterized by tremendous

energy and progression in its opening movement. Yet there’s

a feeling of a work fully formed rather than experimental. The

contrast marked ‘calmante’ (tr. 10 0:47) is clearly observed

yet still fresh, as is the tranquillo second theme flute

solo (0:57). The many instrumental solos emerge in this performance

in a more purposeful and assertive manner than in the 1998 Hallé

Orchestra/Kent Nagano recording (Apex 2564673917). In this way

Gardner achieves a greater sense of urgency and community working

together. This is also partly because he uses a smaller body

of strings: Britten’s recommendation. Gardner reveals more clearly

how the slow movement Variations develop from the first movement’s

second theme, settling early on with an expressive duet by violins.

Again his greater sense of urgency brings a more affirmative

flute and oboe duet which seems naturally to lead to the burgeoning

of the first violins’ climax. This is before the horn has the

closing solo against a backdrop of serene high violins. In the

Tarantella finale Nagano supplies more density of tone but Gardner

has more rhythmic bite and a crisper contrast between the strings’

material in quavers and the woodwind’s semiquaver swirls.

This is a wonderful collection showcasing Britten’s mastery

of both dramatic and poetic setting. His ability to distil a

range of moods and responses is deeply impressive. This is even

more so when contemplating an Elizabethan composer’s inspiration,

his skill in creating musical portraits and an unconventional

yet often expressive and always stimulating Sinfonietta. Moreover,

the juxtaposition of early and late works makes you appreciate

how well Britten applied his mature perspective, especially

in the string orchestra arrangement of the original piano accompaniment

of Lachrymae. It succeeds because of the excellence of

the performances.

Michael Greenhalgh

|

|