|

|

|

availability

CD:MDT

AmazonUK

|

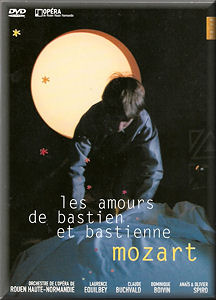

Wolfgang

Amadeus MOZART (1756-1791)

Les Amours de Bastien et Bastienne (Bastien und Bastienne,

K46b, formerly K50) (1768)

Élisabeth Calleo (soprano) - Bastienne; Michael Slattery

(tenor) - Bastien; Martin Winkler (bass) - Colas; Olivier Cesarini

(soprano) - the boy; Claude Buchvald, director; Dominique Boivin,

choreographer; Anaïs and Olivier Spiro, film directors

Élisabeth Calleo (soprano) - Bastienne; Michael Slattery

(tenor) - Bastien; Martin Winkler (bass) - Colas; Olivier Cesarini

(soprano) - the boy; Claude Buchvald, director; Dominique Boivin,

choreographer; Anaïs and Olivier Spiro, film directors

Compagnie Beau-Geste; Orchestre de l’Opéra de Rouen/Laurence

Equilbey

rec. Opéra de Rouen, France 2007. NTSC, picture format 16:9,

region code 0 or PAL region 2. No libretto or synopsis included..

Sung in German with English, French and German subtitles

NAÏVE V5098 [63:00]

NAÏVE V5098 [63:00]

|

|

|

We are not exactly overwhelmed with recordings of Mozart’s early Singspiel Bastien und Bastienne. The only current generally available versions of the whole opera appear to be two mid-price Berlin Classics recordings, one a 2-CD set conducted by Max Pommer, coupled with Apollo and Hyancinthus (0183702BC), the other a single CD, coupled with two arias (Helmut Koch, 0092192BC), and Decca’s Mozart Complete Operas (478 1600). Some dealers have a rival DVD version, coupled with Der Schauspieldirektor and performed at the Salzburg Marionette Theatre (DG Unitel 0734244).

Though it was written when Mozart was 12, the music is worth hearing, but not, I would suggest, until you have got to know his other operas. Weiskern and Mozart’s other librettists based their text on Les amours de Bastien et Bastienne, by Marie-Justine-Benoît Favart and others, itself a parody of Rousseau’s immensely popular opera Le devin du village, the village soothsayer, hence Naïve’s decision to return to the French title for this performance, though this is not explained in the notes. For full details see Neue Mozart Augabe, Bärenreiter, 1974, pp.vii ff.

Whether this is the right version for you will depend on how much extraneous matter you can take - this is very much Bastien und Bastienne plus, with the usual 47 minutes or so extended to 63. The action opens with a boy reading under the sheets by torchlight just after midnight, then wandering down to the theatre above which he appears to live. We hear a distant orchestra as he descends and he is followed by an evil-looking satyr- or faun-like being.

As the boy sits in the stalls, with the faun a few rows behind, an elegantly dressed lady in red, with a red scarf over her eyes comes onto the front of the stage in front of the curtains. This is, we learn later, die edle Frau vom Schloße, the noble lady from the big house. Though she never appears in the opera proper, we are asked in the notes to imagine that this is the end of a putative first act in which Bastien has been playing the part of her toy-boy - and here he comes, also dressed in a red coat to confirm it. It’s his turn to don the red scarf in the game of blind man’s buff.

As the Intrada - not strictly an overture - plays, we hear weird off-stage cawings and hootings. More fauns appear before Bastienne enters, pulling a large ball of cotton wool which emits sheep-like noises. These symbolic sheep seem to be the operatic game of the moment - they also appear, most annoyingly, from time to time throughout the Unitel/Cmajor DVD of Handel’s Admeto which I reviewed recently - here. The distraction of the sheep and the prancing fauns means that we hardly notice the stylishness of the orchestral playing, or of Élisabeth Calleo as Bastienne - she is just right for the role, with a fine but smallish voice and an innocent manner.

Her costume is a mixture of periods but the modern-looking white socks are doubtless meant to emphasise her innocent nature. Later, however, when she dons a red dress and red high-heel shoes and affects to disdain Bastien, she also does the haughtiness well.

A strange figure appears in enlarged silhouette at the rear of the stage. It’s Colas, the fairy-godfather figure of the opera, though he has yet to make his appearance. Before he does so, the fauns dance one of Mozart’s German Dances - there are several such interpolations from the Serenade, K100, Divertimento, K131 and Dances, K509, 600 and 602, to bulk out what is in its proper form a very short work. I have no objection to this, but why do the dancers have to assume such an ugly faun-like guise, when the score actually names them as einige Schäfer und Schäferinnen, several shepherds and shepherdesses? (See Neue Mozart Ausgabe, p.2).

Colas rises from the trapdoor. If Bastienne is in vaguely modern dress, he looks vaguely eighteenth-century with a bicorn hat and a long military greatcoat. Martin Winkler’s stage presence and singing steal the show, but it is almost inevitable that the semi-magic figure of Colas should do so. We could, however, have done very well without the faun in the stalls stealing some of the limelight at this point as he molests the boy and tries to eat his fleecy slippers, or the other fauns messing around on stage - indulging in such wholesome pastimes as picking imaginary fleas off one another and eating them. The explanation in the notes of the woodland setting and the inclusion of these creatures left me unconvinced: the score actually specifies as the scene Ein Dorf mit der Aussicht ins Feld, a village with a view onto a field.

The simple Singspiel is swamped by and at times disappears beneath all this extraneous material. I’m afraid that’s par for the course nowadays, as the production of Admeto to which I have referred demonstrates. Spoken dialogue and singing alike are interrupted by it - as, for example, when Colas gives Bastienne’s ‘sheep’ to the fauns to tear apart and consume. To complicate matters, Bastienne appears to accept the fate of her ‘sheep’ with a shrug and allows herself to be fondled offstage by the fauns, watched by the boy.

Now Bastien appears, wearing a red coat and with the fine lady’s scarf around his waist, in case we miss the point of where he has been. He actually tells us in his first number that he has been with the chatelaine and is returning to his true love, Bastienne, but producers seem to think that we don’t listen to what is being sung. As he sings of his love for Bastienne, Michael Slattery’s voice is as appropriate to the part of Bastien as Calleo’s to that of Bastienne: in his case, an attractive light tenor. The boot is now on the other foot: Bastien is amazed that Bastienne could desert him, but Colas convinces him that it is so.

Winkler clearly revels in his role as manipulator of, as well as father-figure to, the lovers. His aria Diggi, daggi, shurry, murry is the centre point of the work and he sings it with real gusto, aided by some of the less unnecessary stage- and sound-effects. One could perhaps wish for a Colas with a slightly stronger voice: Winkler would not, I think, make a good Sarastro, but Mozart was still very far from turning Singspiel, into the miracle of Zauberflöte. What we really need in the part is someone like Bryn Terfel, whose rendition of this little aria on his Mozart recital pleased Göran Forsling (DG 477 5886 - see review). In the dialogue in particular, it helps that Winkler is a native German speaker. The others are mostly convincing, though Calleo’s soft ch in words like ich sometimes lets her down slightly in the dialogue.

After an interlude in which a topless Bastienne sails through the air on the high wire - presumably a dream, induced by Colas’s magic dust, since she seems simultaneously to be in the dressing-room, with the boy sleeping beside her, molested by the satyrs - the boot is even more firmly on the other foot, with Bastien pleading for a change of heart in vain. Bastienne, now garbed in red by the satyrs, is very definitely in the driving seat. It’s all rather pantomime-like, with Bastien ‘drowning’ himself in the brook, or, rather, the partly-lowered trapdoor, but then Singspiel is meant to be rather slapstick comi-tragedy or tragic-comedy - remember the sample which we’re offered in the film Amadeus. That’s not to say, however, that there are no hints of the mature Mozart-to-be, especially in the duet in which the lovers are gradually reconciled.

All comes right in the end, thanks in part to the intervention of Colas, but it’s not all over until not the fat lady, but the boy treble sings. Now we know why he’s been brought into the action, to round off the entertainment with a charming rendition of the Lied Die Zufriedenheit (K389), with mandolin accompaniment. After a brief resumption of the hectic dance, Colas closes the curtain and the boy walks off through the darkened auditorium as if to emphasise that all the revels now are ended.

The picture quality is good, especially with the up-scaling that my Blu-ray player performs automatically, and the sound quality is equally good heard via the TV, but especially when played via my audio system. I could have done without the very close close-ups of Colas’s stubble and the boy’s teeth braces, however. The single-page synopsis in the booklet is all too short and sweet: I should have preferred more of it and less of the slightly pretentious ‘interpretation’ which runs to double the length of the synopsis. The English subtitles are accurate and idiomatic, though at times they paraphrase rather than translate - but I still think that it would be more helpful to be able to have the German and English on screen together.

A good, enjoyable performance, then, and the additional Mozart music is a bonus addition to the short score. I found the interpolated action a real distraction, but others may be less aware of it, or even like it. Someone must like this sort of thing, since it keeps happening: I’m even more irritated by the DVD premiere of Handel’s Aci, Galatea e Polifemo (Dynamic 33645) on which a perfectly good performance is ruined by having two each of the principal characters, one of each pair miming and emoting the words of the other.

Brian Wilson

|

|