|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound Samples and Downloads

|

Robert Livingston

ALDRIDGE (b.1954)

Clarinet Concerto (2004) [27:17]

Samba (1993) [5:23]

Aaron COPLAND (1900-1990)

Clarinet Concerto (1948) [17:04]

David Singer (clarinet)

David Singer (clarinet)

A Far Cry Orchestra (concertos); Shanghai Quartet (Samba)

rec. Mechanics Hall, Worcester, Massachusetts, USA 5 October (Aldridge

concerto), 10 November (Copland concerto) 2008; Immaculate Conception

Church, Montclair, New Jersey, USA 17 December 2009 (Samba)

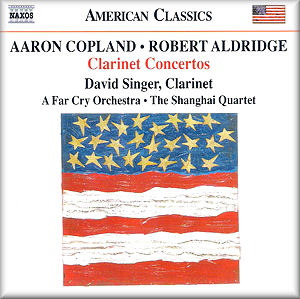

NAXOS 8.559667 [49:44]

NAXOS 8.559667 [49:44]

|

|

|

Robert Aldridge’s Clarinet Concerto is a charming new work which should appeal to just about any listener. It is the direct contemporary descendant of romantic concertos, tuneful, well-built in the old-fashioned way and quite pleasing, but still recognizably new. A listener from the nineteenth century would recognize the form of each movement and the basically tonal language, but not the ebullient, outdoorsy adventurousness of it all.

Aldridge’s achievement here is to take a huge palette of influences and produce a satisfying new product. In describing this music, one might start by naming Aaron Copland, recalling the adventurous musical tastes of Benny Goodman, and wondering if a bit of late Brahms can be heard here and then. Add to that hints of Gershwin, a generous dollop of jazz, and, right in the middle of the slow movement, a klezmer episode, and you have the recipe for what sounds like a mess - but in fact is an almost seamless new style of Aldridge’s own.

The concerto begins with an insistent sense of motion among strings and timpani; this gives way to the solo clarinet, which intones the mellow main theme. The tune sounds like a lonesome jazz ballad which has left home and struck out for new musical territory. As the orchestra picks up the theme, the clarinet loops and weaves around it to wonderful effect. The second subject is lyrical, providing the clarinetist opportunity to feel a little blue. In terms of formal structure and development, and in its mixture of virtuosic note-spinning and pure bluesy gorgeousness, this first movement has a great deal in common with that of the Ravel Piano Concerto in G.

The slow movement, also the longest and best, is still and (as the composer directs) “serene” for the most part, but occasionally gets interrupted by klezmer outbursts. I have no problem with klezmer outbursts, and quite enjoyed this one, but it did occur to me that this moment sounds an awful lot like the corresponding one in Mahler’s First. It also struck me that the clarinet is such a great klezmer instrument, but for the most part Aldridge entrusts the main tune to the brass, especially at the end. Never mind: the rest of the slow movement is in the hands of the clarinet and muted strings, who together unfold a gorgeous late-night love song. The last few seconds are pricelessly beautiful.

After this the finale explodes with excitement. Again the klezmer influence is present, for a perpetuum mobile in which the clarinet triumphs against an all-out assault from the orchestra. At the fourth minute the double basses drop their bows and begin to pluck out a jazzy new beat, but as the concerto ends the music’s energy is stirring up trouble once again. This concerto is consistently tonal, highly accessible, recognizably “American” in its vibrancy and eclecticism, and above all very fun, and I am very happy to report that it gets better on each successive listen.

Aaron Copland’s Clarinet Concerto is the coupling. It is just seventeen minutes to Aldridge’s less concise twenty-seven. Within seconds the clarinetist is singing the gentle main theme, and the first movement is so beautiful that it seems to end as suddenly as it began. A jazzy cadenza, with hints of tunes that might do Benny Goodman proud (it was written for him), leads seamlessly into the quick finale. Robert Aldridge makes a return appearance as composer of the encore, a Samba for clarinet and string quartet. This one’s another delight, with vigorous strings and joe-cool clarinet a happy example of opposites attracting. At around 1:40 the violins introduce a beautiful dance tune which offers contrast, and a sneak preview of what the Brazilian version of West Side Story might sound like.

David Singer, longtime clarinetist for the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, is the excellent soloist. The Aldridge concerto was written for him, and his love for it shows at all times. He plays tenderly when needed, with the sort of beautiful simplicity that is anything but simple to bring off. I thought more than once how much I would like to hear his work in the clarinet solo from Appalachian Spring - then realized that, since I own the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra’s recording of that work, I already have heard him play it!

Singer also deserves praise for this performance of the Copland: listen especially to how he handles the transition from the opening nocturne to the jazzy climax of the cadenza, and into the finale. This work has been recorded before, many times, most obviously by Goodman himself, a recording which I am a bit ashamed not to own. One contemporary clarinet star to have tackled the work is Martin Fröst, alongside the Malmo Symphony on BIS; they indulge in a first movement a full minute longer than this one. It is a philosophical difference: Fröst is playing a nocturne, while Singer evokes the kind of “western” Americana Copland one hears in Appalachian Spring. And Singer’s cadenza wins hands down: jazzier, peppier, and with the best transition into the finale I’ve heard.

The Shanghai Quartet have really mastered the difficult Samba, and A Far Cry Orchestra excels in the two concertos. I had never heard of this group before, but the biography (which lists every musician on the album) explains that it is a self-conducted Boston-based ensemble of just thirteen string players. For the concertos (Aldridge calls for woodwinds and a timpani, Copland for a piano) the A Far Cry musicians have invited a few friends along. In the Copland first movement, A Far Cry does not provide the sort of lyrical support one finds on full-orchestra recordings with glowing violin sections, but they are more incisive and clearer in the finale, so it is a matter of taste.

The booklet notes, by Aldridge and Singer themselves with a note from producer Donald Palma, are helpful and descriptive, and if the composer and clarinetist are a little congratulatory to each other (Aldridge calls this “the best recording of the [Copland] that I have ever heard” ), I cannot blame them. Indeed, I cannot help but agree. This disc is, as Singer writes, “a labor of love” and the product of years of collaboration. I feel glad composer and players have shared their labor of love with us. The program, the compositions, the performances, and the sound are outstanding.

Brian Reinhart

|

|