|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound

Samples & Downloads

|

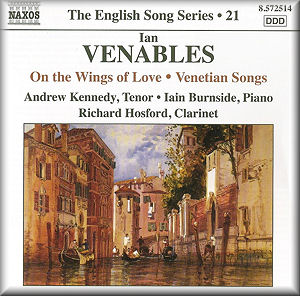

Ian VENABLES (b.1955)

On the Wings of Love, Op.38 for tenor, clarinet and piano

(2005-2006) [23:15]

Venetian Songs - Love’s Voice, Op.22

(1994-1995) [15:37]

Midnight Lamentation, Op.6 (1974) [3:42]

Break, break, break, Op.33, No.5 (1999) [2:24]

The November

Piano, Op.33, No.4 (1999) [2:56]

Vitae Summa Brevis,

Op.33, No.3 (1999) [3:24]

Flying Crooked, Op.28, No.1 (1997)

[1:03]

At Midnight, Op.28, No.2 (1997) [3:51]

The Hippo,

Op.33, No.6 (1999) [1:28]

At Malvern, Op.24 (1998) [4:22]

A Kiss, Op.15 (1992) [4:01]

Andrew Kennedy (tenor); Iain Burnside (piano); Richard Hosford (clarinet)

Andrew Kennedy (tenor); Iain Burnside (piano); Richard Hosford (clarinet)

rec. Wyastone Concert Hall, Monmouth, UK, 23-25 November 2009. DDD

NAXOS 8.572514 [66:04]

NAXOS 8.572514 [66:04]

|

|

|

Two things need to be understood when approaching the songs of Ian Venables. Firstly, his music sits fairly and squarely in the tradition of English vocal music. From the Elizabethan lutenists to Tippett by way of Finzi and Warlock, it is easy to detect influences and allusions. Venables typically writes in a largely tonal - sometimes stretched a bit - idiom that is usually both approachable and memorable. Furthermore even the briefest of glances at the list of poets that he has chosen to set, reveals many names that are a part of the English literary tradition. These include Tennyson, Hardy and Harold Monro (1879-1932). The second point is an outworking of the first. There is absolutely no way that Venables’ music is derivative or pastiche of any other composer, living or dead. This is not ‘souped-up’ Finzi or exhumed Moeran or anyone else. It would be like saying that Bach’s music was only Böhm or Buxtehude with ‘knobs on’. Venables is his own man: he writes what he pleases. At times his music is less likely to have an instant appeal but often the effect is immediate. What lies at the bottom of Ian Venables’ art is his willingness to have listened to other composers, to have absorbed their style and message and to have synthesised a new musical voice that is in their musical trajectory but is not beholden to it.

Finally, one or two characteristics that are nearly always present in Venables’ songs are a deep response to the text - frequently the poets too - and the ability to move the listener, often beyond the call of duty. Much of his music is melancholy: it is often beautiful and is always well-crafted.

The present CD introduces the listener to a number of songs and cycles: some of these are well known to British music enthusiasts, but others are first recordings and are therefore valuable additions to his catalogue.

I was seriously impressed by the song-cycle On the Wings of Love which is a setting for tenor, clarinet and piano of poems by a variety of non-English writers. It was composed in 2005-2006. I rely heavily on the composer’s web pages and the sleeve-notes for my comments on this work.

The title of the song-cycle was taken from Plato’s Symposium which is that philosopher’s great discourse on the nature of love. Venables has attempted to explore the ‘universal theme of love in its widest possible sense and not just in the realm of human affections’.

The composer chooses a number of texts from poets old and modern, and from a variety of backgrounds and countries. The first song is a setting of Constantine P. Cavafy’s ‘slippery time’ poem, ‘Ionian Song’, where he suggests that in spite of the old gods having been thrown down and their temples destroyed, they are still watching over their land. Venables has interpreted this poem in a subtly timeless manner: he has created a fine balance between a relatively ‘modernistic’ declamatory style and a heart-achingly beautiful lyricism. This song is a masterpiece. The key to the poem is the line: - ‘O Ionian land, it is you they love still.’ It is a notion that all who love Greece and the ‘classics’ have probably entertained at some time in their life. The latter part of the song paints a glorious picture of the god Apollo passing over the Arcadian Hills.

The second song, ‘The Moon sails out’ is a surrealist poem by Federico Garcia Lorca that presents the poet’s reaction to an evening spent in the moonlight where the ‘comforting world of daylight has been replaced by a nocturnal world of shadows and dreams.’ The music moves at a gentle pace and has a certain questioning feel to it. The clarinet and voice interweave to create a magical nocturne.

‘Sonnet XI’ by Jean de Sponde, the sixteenth century French poet, is about love and constancy. The composer opens this song with an almost Debussian bit of impressionism. The balance between piano and clarinet is perfect. It makes me hope that one day Venables will write a clarinet concerto or sonata! The slow-paced vocal line initially complements the poet’s theme; however the middle section is more passionate with the singer reflecting on his ‘loving you, I love without regret’. The magical mood returns but not before a final outburst from the soloist announcing that ‘My fire, till I am dead, will never die.’ It is the climax of the song and of the cycle.

The fourth song is by the Emperor Hadrian of ‘Wall’ fame. He ruled from AD117 to 138 and was a great soldier. However, he is known to have written a deal of poetry. Alas, there are now only fragments left. One of these is an ‘Epitaph’ that the Emperor wrote for himself. It is such a simple, yet ultimately profound, universal sentiment:-

Little Spirit,

Gentle and Wandering,

Companion and guest of the body,

In what place will you now abide,

Pale, starry and bare,

Unable as you used, to play

Venables has matched the simplicity of the poem with music that is equally straightforward. The piano accompanies a thoughtful vocal line with simple chorale-like chords. The clarinet is only heard at the opening and close of this song. Once again the listener is struck by the composer’s ability to ‘stop time’ in his music.

I was a wee bit confused by the next song. In the programme notes for this song-cycle on the Venables website, the composer mentions a setting of ‘Reluctance’ by the American poet Robert Frost. However, this has not been recorded here: I understand that this is due to copyright reasons.

The last is a setting of W.B. Yeats’ poem ‘When you are old.’ It opens with a long instrumental prelude – in fact I was beginning to wonder when the voice would enter! Once more this is a slow-paced song, designed to complement the idea of ‘When you are old and grey and full of sleep, and nodding by the fire...’

The general impression of this beautiful cycle is of stillness, reflection and a deep sense of peace, in spite of a few passionate irruptions. It is a piece that needs concentration and possibly works best in the listener’s music-room rather than in the concert hall. It brooks no distraction. It is one of Ian Venables’ greatest compositions proving that he belongs fairly and squarely in the tradition of the great English song composers.

I am particularly delighted to review the setting of John Addington Symonds’ Venetian Songs –Love’s Voice. Like many, I guess that I associated him with prose writings on the Renaissance and on Greece and Italy. However, Venables has pointed out to me a whole corpus of poetical works, many of which approach genius. In the same way as Gerald Finzi deeply identified with the poetry of Thomas Hardy, Ian Venables has made a ‘chosen identification’ with Symonds’ poetry. Graham Lloyd has written that this is ‘an empathy borne from a shared philosophical outlook on life: and a common conviction about nature and purpose of artistic endeavour.’ I recommend that the listener explore John Addington Symonds’ poetry – much of which is easily available on-line.

The first song is called ‘Fortunate Isles’. Once again, the impressionistic mood of the composer’s musical language seems to come to the fore. This song floats in the air rather like the islands on The Lagoon: there is little doubt that this poem was written about Venice and its surroundings - places very dear to the poet’s (and composer’s) heart.

The next song is ‘The Passing Stranger’. It is quite obviously a meditation on the nature of ‘what might have been’ a notion that surely crosses our minds, especially as we get older. The song begins and ends quietly but builds to an impassioned climax for the middle lines – ‘Whereby the soul aspires to God above ...’ There is a careful use of dissonance in this setting that highlights the sense of the poet’s ‘disorientation’ and reflection.

For anyone who has taken a trip on a gondola on the canals of Venice, the third song will bring back memories. In the ‘Invitation to the gondola’ the poet evokes Venice as ‘a city seen in dreams’. It is surely one of the finest poetic descriptions of that city. Venables has taken this love poem, for love poem it is, and has created a mood and impression that mirrors the movement of the gondola and the lapping of the waters as the ‘lamp-litten’ city ‘gleams, with her towers and domes uplifted ...’

The final song, incidentally dedicated to Ian Partridge, is the eponymous ‘Love’s Voice’. The message of this poem is based around Tennyson’s ’Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all’. Once again the topographical setting of this poem would appear to be Venice, however it is very much a universal topic that could be situated anywhere that has ‘glimmering water-ways’. The music is reflective and introverted, but is ideally suited to the dark mood of the poem.

It is good to have a recording here of Ian Venables’ early ‘Midnight Lamentation’. This delightful song was written when the composer was only nineteen years old. This deeply melancholic poem was written by the Georgian poet Harold Monro and is summed up in the near tragic final verse – ‘I cannot find a way/Through love…’ The music that Venables has written is a perfect complement to the ultimately heart-rending words. I agree with Graham Lloyd’s conclusion that this setting is a ‘powerful interpretation of a profoundly moving poem’. Future musicologists will study this song in detail to find intimations of the composer’s subsequent development as a composer; however the artistic value of this song is beyond doubt. It is an impressive essay from a teenager!

The ‘batting order’ for the four songs drawn from Venables’ Op.33 is a bit cock-eyed. Furthermore, I guess that I was a little disappointed that Naxos could not manage to squeeze in the other two songs from Op.33 which are ‘The Way Through’ (Jennifer Andrews) and ‘It Rains’ (Edward Thomas) and given them in order. However, this is nit-picking when one considers all the good things that are on this disc.

‘Break, break, break!’ is the first poem from Op.33 presented on this disc. It’s a splendid sea-piece complete with the piano accompaniment providing a musical representation of the surging of the waves. The vocal line is particularly beautiful and constantly reflects the development of the poet’s ideas. It is a requiem for broken-hearted loss, and a nostalgic reflection for what was, but can never be again.

‘The November Piano’ is a setting of a poem by Charles Bennett taken from his first volume of poetry Wintergreen which was published in 2002. Of all the songs on this disc, I found this the hardest to come to terms with. Perhaps the poetic imagery needs a little thought? It would have helped to have the words of the poem in the liner-notes; however it is still in copyright. In a programme note for this song, Graham Lloyd has written that it ‘contains all the hallmarks of the composer’s mature style: the use of long-breathed vocal lines, melisma, underpinned by a rich and complex harmonic language.’ It is a song that I need to explore further, possibly with a copy of the score.

I have always loved and appreciated Ernest Dowson’s poems 'Cynara' and ‘Vitae Summa Brevis’. It is unfortunate that he is largely forgotten except for these two masterpieces. The line 'They are not long, the days of wine and roses ...’ has become part of the popular imagination. Ian Venables has devised a straightforward strophic setting of this poem that reflects the simple but profound thought of the poem. The composer’s style in this song is similar to his early ‘Midnight Lamentation’ rather than the more advanced ‘The November Piano’. There is a feeling of resignation about the transience of life reflected in this song which echoes the artistic achievement of Gerald Finzi without in any way parodying his language.

‘The Hippo’ by Theodore Roethke is one of the loveliest little songs in the repertoire. It would be easy to dismiss this as a ‘childish’ song, yet in many ways it reflects a good attitude to ‘slowing down a bit’ in life. It may well be a good way to live …

The five remaining songs on this disc are all ‘old favourites’: it is appropriate to have another recording of them easily available. They are quite definitely ‘entry level’ to Venables’ catalogue. I would recommend that new fans of this composer begin here.

I have always treasured Robert Graves' delightful poem about the ‘haphazard’ flight of the cabbage white butterfly. I guess gardeners largely despise this ‘pest’, but since being a child I have loved to watch them in the garden. Both poem and setting are evocative of this beauty and child-like innocence. It is a remarkably short work, but contains a variety of harmonic and vocal devices that reflect the butterfly’s progress. The song has largely become Venables’ greatest hit: it was composed at the request of the late Lady Bliss.

Edna St. Vincent Millay’s beautiful poem ‘At Midnight’ is a backward glance at her past love affairs written in the form of a sonnet. For me the most moving lines are ‘I cannot say what loves have come and gone / I only know that summer sang in me / A little while, that in me sings no more.’ There is a surprising sparseness to this music that belies the romantic nature of the words. Yet there is a growing intensity that complements the sense of the poem. It is a fine example of a love poem set to music.

I have written extensively on Venables’ setting of John Addington Symond’s ‘At Malvern’: little more need be said here. However, it has been noted that the poem suggests that the poet has ‘evoked the calm and serenity of Malvern in the 1860s where little could be heard, but the sounds of nature and the distant bells of the famous priory’. I believe that this misses the point of the poem. What may seem to be a pastoral idyll is in fact a cry from the heart of a poet who is suffering from confusion, frustration and angst: it is played out against the rural backdrop of the Malvern Hills. This dichotomy is a sentiment that is well expressed by both the words and the music.

I have always hoped that Ian Venables would set Edward Thomas’s poem ‘Adlestrop’. I believe that his style and musical language would be ideal in creating a sense of stasis felt on that famous hot summer’s day. However, at the moment I have to be content with his application of this mood to Thomas Hardy’s love poem ‘A Kiss.’ The concern of this poem is to balance an ‘innocent love’ with ‘love as an eternal theme’. Venables has chosen to counterpoise a diatonic vocal melody with a relatively chromatic accompaniment. This seems to represent these two pictures of love. Interestingly, Ian Venables once told me that ‘A Kiss’ is ‘perhaps stylistically the closest I get to Finzi’. However he is adamant that any ‘aural references were not conscious ones’.

The quality of the performance by Andrew Kennedy and Iain Burnside is superb. And let us not forget the fine contribution made by the clarinettist Richard Hosford in On Wings of Love. This is an ideal presentation of Ian Venables’ music that is essential to all enthusiasts of English music in general and English lieder in particular.

John France

|

|