|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

Sound

Samples & Downloads

|

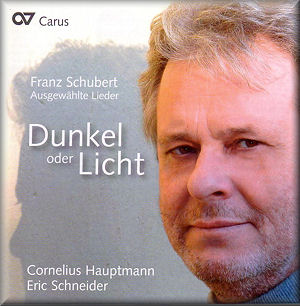

Dunkel oder Licht

Franz SCHUBERT (1797-1828)

Der Strom, D. 565 [1:42]

Auf der Donau, D. 553 [3:25]

Fahrt zum Hades, D. 526 [4:30]

Grenzen der Menschheit, D. 716 [7:08]

Der Pilgrim, D. 794 [4:33]

Grablied für die Mutter, D. 616 [2:32]

Hoffnung, D. 637 [2:54]

Wandrers Nachtlied, D. 768 [2:19]

Die Mutter Erde, D. 788 [3:32]

Der Jüngling und der Tod, D. 545b [3:52]

An der Tod, D. 518 [1:20]

Der Tod und das Mädchen, D. 531 [2:29]

Totengräberweise, D. 869 [4:56]

Totengräberlied, D. 44 [2:28]

Das Grab, D. 569 [3:24]

Totengräbers Heimweh, D. 842 [6:19]

Litanei auf das Fest Allerseelen, D. 343 [2:08]

Cornelius Hauptmann (bass); Eric Schneider (piano)

Cornelius Hauptmann (bass); Eric Schneider (piano)

rec. Spring 1996, Reitstadel, Neumarkt, Germany

CARUS-VERLAG 83.359 [59:34]

CARUS-VERLAG 83.359 [59:34]

|

|

|

This recital was recorded in 1996, but I can find no evidence

of any previous release. It comes out now on the house label

of the distinguished German music publisher, Carus-Verlag. The

recording is full and rich with balance between voice and instrument

as close to perfect as you could wish. The booklet prints all

the sung texts in German with English translation. There is

some general information about the singer and the accompanist,

but nothing about the music. Instead you will find a rather

pointless essay by Hera Lind in which she reflects on the nature

of the programme.

And the programme, entitled “Dark or Light”, is

made up entirely of songs on the subject of mortality and death.

We shouldn’t be surprised, then, if the overall effect

is sombre. Cornelius Hauptmann has the perfect voice for this

repertoire. His recorded credits include Sarastro with Sir Roger

Norrington, as well as many others where a real bass voice is

required. His lower register is strong and true, and though

he does manage to lighten the tone when required, there’s

very little even of a baritone quality when he ventures into

the upper reaches. The voice is darkly beautiful, and he sings

throughout with understanding and intelligence.

His accompanist, Eric Schneider, proves a splendid partner.

His playing is full of character, the duo a real collaboration.

Inevitably, many of the songs are given in transposition for

low voice, and this does not make life easy for the pianist.

Transposed down a major third to G flat major, the accompaniment

to Hoffnung, for example, could sound very gruff indeed.

But Schneider works wonders with it, as does Graham Johnson,

only a semitone higher, accompanying the divine Marjana Lipovšek

on Hyperion. The song is a tricky one to bring off: its title,

“Hope”, leads us to expect an optimistic song, but

there is considerable irony too, with references to planting

hope on one’s grave. Hauptmann is very successful in the

role of insouciant youth, but also possesses just the right

gravity to encompass the other elements in the song. At a slightly

faster tempo, Marjana Lipovšek is more seductive. Both

views are valid and satisfying.

Hauptmann’s ability to bring variety of colour into his

singing is evident in the pianissimo passages in Wanderers

Nachtlied. The real test, however, is how well he manages

to impersonate the Maiden in D. 531; Death, we might think,

will come more naturally to him. In fact he manages very well,

and it is only in direct comparison with one or two female singers,

notably Brigitte Fassbaender, again on Hyperion, that one hears

the breathlessness of the Maiden’s entreaties brought

out in a more natural way. Hauptmann’s reading is nonetheless

very convincing, and his voice serves him wonderfully well for

the second part of the song, though some will find the final

bottom D flat is perhaps one sepulchral note too far.

The programme has been well devised, with some lighter moments.

Totengräberweise, already surprisingly cheerful,

is followed by a gravedigger’s song that could almost

be a buffo aria from a Mozart opera. In both cases the singer

characterises very well, skilfully lightening his voice the

better to bring out the comic elements in D. 44.

A dark, bass voice is a considerable advantage in a song such

as Das Grab. Here, with alarming prescience and daring

for a twenty year-old, Schubert frequently has the voice and

piano in unison, the more to evoke the cold stillness of the

grave. Hauptmann sings three of the prescribed five verses of

this song.

This most satisfying recital ends with the beautiful “Litany

for the Feast of All Souls”. Hauptmann and Schneider create

a wonderfully calm atmosphere here, and the performance is one

of the finest of all. It is disappointing, however, and puzzling

too, that of the many verses of this strophic song - the poem

appears to have seven verses - they choose to perform only one.

Janet Baker, with Geoffrey Parsons on EMI, sings three, which

is probably enough. But to hear the sublime three-bar piano

postlude only once is a pity, and Hauptmann’s performance

certainly sounds incomplete.

William Hedley

|

|