|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound

Samples & Downloads

|

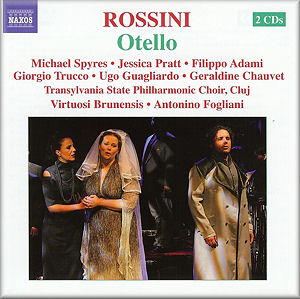

Gioachino ROSSINI

(1792-1868)

Otello - Dramma in three acts. (1816)

Otello, an African in the service of Venice - Michael Spyres (tenor);

Desdemona, the lover and secret wife of' Otello - Jessica Pratt

(soprano); Elmiro, Desdemona’s father - Ugo Guagliardo (bass);

Rodrigo, Desdemona's unsuccessful suitor - Filippo Adami (tenor);

Iago, Otello’s secret enemy - Giorgio Trucco (tenor); Emilia,

Desdemona's confidante - Geraldine Chauvet (mezzo); The Doge, Sean

Spyres (tenor); Lucio, Otello's confidant - Hugo Colin (tenor);

A Gondolier, Leonardo Cortellazzi (tenor)

Otello, an African in the service of Venice - Michael Spyres (tenor);

Desdemona, the lover and secret wife of' Otello - Jessica Pratt

(soprano); Elmiro, Desdemona’s father - Ugo Guagliardo (bass);

Rodrigo, Desdemona's unsuccessful suitor - Filippo Adami (tenor);

Iago, Otello’s secret enemy - Giorgio Trucco (tenor); Emilia,

Desdemona's confidante - Geraldine Chauvet (mezzo); The Doge, Sean

Spyres (tenor); Lucio, Otello's confidant - Hugo Colin (tenor);

A Gondolier, Leonardo Cortellazzi (tenor)

Transylvania State Philharmonic Chpoir, Cluj.

Virtuosi Brunensis/Antonio Fogliani

rec. live, Kursaal, Bad Wildbad, Germany, 12, 17, 19 July 2008 during

the 20th Rossini in Wildbad Festival in the new revised edition

after the autograph and contemporary manuscripts by Florian Bauer

NAXOS OPERA CLASSICS 8.660275-76 [68.56 + 79.34]

NAXOS OPERA CLASSICS 8.660275-76 [68.56 + 79.34]

|

|

|

Most people know Rossini by his comic opera Il Barbiere di

Siviglia premiered in 1816 and never out of the repertoire

throughout its life to the present day. Despite being the most

famous opera composer of his times the same cannot be said of

the other of his thirty-eight operatic compositions. This is

particularly so in respect of his serious operas (opera seria)

and non-more so than those he composed during his time as music

director of the Royal Theatres of Naples, a coveted post. Changing

fashions that followed the emergence of first Verdi, then Puccini

and the verismo composers, contributed to this. Also important

were the consequential changes in the character of voices that

came into being to sing these latter works. This in turn led

to the decline, until the last twenty or so years, of lighter

more flexibly-voiced singers able to cope with the demands of

the florid music involved. It is necessary to be aware of some

of the background to the Naples opera seria such as Otello

fully to appreciate its revolutionary qualities.

Otello was Rossini’s nineteenth opera and the second

of the nine opera seria composed for the Royal Theatres

of Naples. These came about as a result of the recognition by

Barbaja, the powerful impresario of the Royal Theatres of Naples,

of Rossini’s pre-eminence among his contemporaries. Barbaja

summoned Rossini to Naples and offered him the musical directorship

of the Royal Theatres, the San Carlo and Fondo. The proposal

appealed to Rossini for several reasons. First, his annual fee

was generous and guaranteed. Secondly, and equally important,

unlike Rome and Venice, Naples had a professional orchestra.

Rossini saw this as a considerable advantage as he aspired to

push the boundaries of his opera composition into more adventurous

directions. Under the terms of the contract, Rossini was to

provide two operas each year for Naples whilst being permitted

to compose occasional works for other cities. The composer tended

to push the limits of this contract in this latter respect and

in its first two years he composed no fewer than five operas

for other venues, with Il Barbiere di Siviglia being

among four for Rome

In his first Naples opera seria, Elisabetta regina d’Inghilterra,

premiered to great enthusiasm on 4 December 1815, Rossini made

imaginative use of professional musicians and with several innovations.

For the first time he dispensed with unaccompanied recitative

and which added dramatic vigour. He also, for the first time

wrote out in full the embellishments he expected from his singers,

thus avoiding their choosing to show off their vocal prowess

to the detriment of the drama. In Otello Desdemona is

introduced via a duet with Emelia (CD 1 trs.7-8) rather than

the traditional entrance aria. Other innovations occur throughout

the nine Naples opera seria composed during his seven-year

stay.

Rossini went to Rome after the success of Elisabetta

presentingTorvaldo e Dorliska at the Teatro Valle (26

December 1815), and after a hectic period finding a libretto,

Il Barbiere di Siviglia at the Teatro de Torre

Argentina. On his return to Naples he found the San Carlo had

been destroyed by fire. He composed his only Naples opera buffa,

La Gazetta, premiered at the small Teatro de Fiorentina

on 26 September 1816. This premiere had been postponed because

Rossini was indulging his social life to the full, as was his

wont. Perhaps the soprano Isabella Colbran, then the mistress

of Barbaja, and later Rossini’s wife, was also distracting

him. Certainly Barbaja was getting tetchy with the delays in

the completion of the scheduled Otello. He wrote to the

administrator of the Royal Theatres about Rossini’s dilatoriness

in providing the finished work whilst being active with his

social engagements. Otello should have been premiered

on 10 October. It was first postponed for a month

before being eventually staged on 4 December. As the San Carlo

was not yet rebuilt it was staged at the smaller Royal Theatre,

the Teatro del Fondo.

Rossini’s choice of Otello with its tragic ending

was distinctly adventurous. Critics of the libretto assumed

it to be based directly on the Shakespeare’s play. However,

around the late 1970s evidence was presented to the Centre for

Rossini Studies that the source of di Salsa’s libretto

was more likely to have been the play Otello by Baron

Carlo Cozena staged in Naples in 1813. What is certain is that

only in the third act of Rossini’s Otello is there

much relationship with Shakespeare’s play. That act certainly

elicited the composer’s most inspired music with a richly

scored introductory prelude and the interpolation of The

Gondoliers Song (CD 2 tr.12), a brilliant inspiration and

creation. The act also features the only duet for Otello and

Desdemona (CD 2 tr.15). It is set against a growing storm, a

typical Rossinian feature, as the mood moves towards the work’s

dramatic climax. The greatness and sophistication of Rossini’s

music in the third act often blinds critics to the virtues of

that in the first two where the story diverts so much from Shakespeare.

In di Salsa’s libretto Desdemona is secretly pledged to

Otello who has been greeted by the Doge and lauded after his

victory over the Turks in Cyprus. The Doge’s son, Rodrigo,

together with Iago, plots against Otello. Desdemona’s

father Elmiro arranges her marriage to Rodrigo but Otello halts

this and a fight ensues. Iago shows Otello a letter of affection

from Desdemona purporting that it was written to Rodrigo although

it was intended for him. This fuels Otello’s doubts, which

lead to the conclusion of the third act.

Once Rossini was cajoled from the cuisine of Naples and whatever

other extra-mural activities were filling his time, he composed

with speed and felicity. Despite its bloody and tragic ending

the opera was enthusiastically received by press and public

alike. Despite the demand for six tenors, including three outstanding

coloratura tenors, Otello initially spread throughout

the Italian peninsula in its original form. Of particular note

is the confrontation between Otello and Rodrigo in act 2 (CD

2 Trs.7-8) where visceral high Cs from both singersare

required (p179. Rossini. Richard Osborne. Master Musicians

Series. Dent 1987). For a production during Rome’s carnival

in the season of 1819-20 Rossini provided an incongruous happy

ending (lieto fine).

I was particularly interested to hear how Jessica Pratt as Desdemona

measured up to Rossini’s vocal demands in her Willow

Song (CD 2 Trs 13-14) having been impressed by her in the

eponymous role in the British premiere of Rossini’s Armida

at Garsington in 2010 (see review).

As there, she could articulate the words better, but she sings

the role with consummate musicality, strength of voice and tonal

beauty. She does have the tendency to give stress to the emotions

of the character by a swell on the note and could perhaps learn

from the likes of Fleming and Caballé who are softer

in attack but equally dramatic. In the eponymous role here Michael

Spyres has the baritonal hue that Rossini accommodated for the

renowned Giovanni David whilst not quite having the freedom

at the top of the voice that is attributed to that famous predecessor.

In the role of Rodrigo, created by Nozarri, the Naples coloratura

tenor par excellence, Filippo Adami copes amazingly well

(CD 2 Tr.6) and, if he is careful, he could have a good career

in this increasingly staged repertoire. Ugo Guagliardo, born

in Palermo, is excellent as Elmiro whilst French mezzo Geraldine

Chauvet is expressive and nicely contrasted tonally with Jessica

Pratt in the duets between Emilia and her mistress (CD 1 Trs.7-8

and CD 2 Tr.11).

Not altogether common among these Naples opera seria

there are rival recordings. That on Philips (475 448 2) dates

back to 1979 and features a not particularly idiomatic Carreras

but a lovely Desdemona by the lyric mezzo Frederica Von Stade

and Elmiro sung by Sam Ramey as its major strengths. At mid-price

there is no libretto; same goes for this Naxos issue. More recently

Opera Rara, in their usual manner gave it the ‘full works’

whilst using the critical edition by Michael Collins for the

Rossini Foundation (ORC 18 see review).

Spread over three full priced discs it comes with full libretto,

translation into English, plus an appendix of variants Rossini

composed for other singers in productions elsewhere. Although

not included, these variations accommodated the famous baritone

Tamburini as Iago in Paris and London in the 1830s where the

work was often sung by the so-called Puritani quartet plus the

tenor Ivanoff.

The Naxos booklet has artist profiles and a good track-related

synopsis. There is a libretto, in Italian at the Naxos

website. The booklet essay has self-conflicting incongruities

(p.5) as to the decline of Rossini’s Otello and

the influence of Verdi’s opera. The acoustic is warm whilst

the applause is polite and not unduly intrusive.

Robert J Farr

see also review by Robert

Hugill

|

|