|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound

Samples & Downloads

|

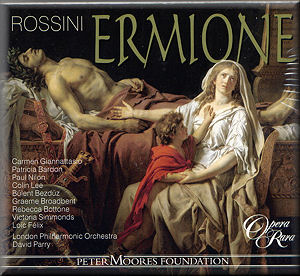

Gioachino ROSSINI

(1792-1868)

Ermione - Opera in Two Acts (1819)

Ermione, rejected lover of Pirro and loved by Orestes - Carmen Giannattasio

(soprano); Andromaca, widow of Hector and a prisoner of Pirro who

is infatuated by her - Patricia Bardon (mezzo); Orestes, son of

Agamemnon - Colin Lee (tenor); Pirro, King of Epirus, betrothed

to Ermione - Paul Nillon (tenor); Pylade, companion of Orestes -

Bülent Bezdüz (tenor); Fenicio, tutor to Pyrrhus - Graeme

Broadbent (bass); Cleone - Rebecca Bottone (soprano); Cefisa - Victoria

Simmonds (soprano); Attalo - Loic Felix (tenor)

Ermione, rejected lover of Pirro and loved by Orestes - Carmen Giannattasio

(soprano); Andromaca, widow of Hector and a prisoner of Pirro who

is infatuated by her - Patricia Bardon (mezzo); Orestes, son of

Agamemnon - Colin Lee (tenor); Pirro, King of Epirus, betrothed

to Ermione - Paul Nillon (tenor); Pylade, companion of Orestes -

Bülent Bezdüz (tenor); Fenicio, tutor to Pyrrhus - Graeme

Broadbent (bass); Cleone - Rebecca Bottone (soprano); Cefisa - Victoria

Simmonds (soprano); Attalo - Loic Felix (tenor)

Geoffrey Mitchell Choir; London Philharmonic Orchestra/David Parry

rec. Henry Wood Hall, London, March 2009

OPERA RARA ORC42 [64.47+69.35]

OPERA RARA ORC42 [64.47+69.35]

|

|

|

As I write, 2010 is becoming quite a year for Rossini

lovers. It has amongst other things seen the staging of his

lesser-known works or their appearance on CD and DVD, often

making them readily available for the first time. This is particularly

true of the nine opera seria that the composer wrote for the

Teatro San Carlo in Naples beginning with Elisabetta, Regina

d’Inghilterra, (Opera

Rara ORC22) the composer’sfifteenth

opera in October 1815 and concluding with Zelmira (Opera

Rara ORC27) his thirty-third in February 1822. This

Opera Rara issue of Ermione, Rossini’stwenty-seventh

and the sixth in the Naples sequence, comescomplete with

full background to the opera as well as a libretto and translation

in English. This recording and performance can stand alongside

the first staged performances of Armida in both Britain

(see review)

and the USA as being particularly significant and welcome.

The nine Naples opera seria came about as a result of the recognition

by Barbaja, the powerful impresario of the Royal Theatres of

Naples, of Rossini’s pre-eminence among his contemporaries.

This had become even more evident after the premieres of Tancrediand

L’Italiana in Algeri in Venice in 1813. These launched

Rossini on an unstoppable career that saw him become the most

prestigious opera composer of his time. Barbarja summoned Rossini

to Naples and offered him the musical directorship of the Royal

Theatres, the San Carlo and Fondo. The proposal appealed to

Rossini for several reasons. First, his annual fee was generous

and guaranteed. Secondly, and equally important, unlike Rome

and Venice Naples had a professional orchestra. Rossini saw

this as a considerable advantage as he aspired to push the boundaries

of his opera composition into more adventurous directions. Under

the terms of the contract, Rossini was to provide two operas

each year for Naples whilst being permitted to compose occasional

works for other cities. The composer tended to push the limits

of this contract and in the first two years he composed no fewer

than five operas for other venues, with Il Barbiere di Siviglia

being among four for Rome

Although not all of Rossini’s nine Naples opera seria

were outstanding successes, only Ermione was considered

to have been an out and out failure. It survived for only five

performances and was then not heard again until concert performances

in Sienna in 1977 and Padua in 1986. The latter seems to have

stimulated the Erato recording of the same year, both

featuring Cecilia Gasdia in the eponymous role, Ernesto Palacio

as Pirro and Chris Merritt as Oreste; Claudio Scimone is the

conductor (Warner

2564 68751-9). The emergence of a provisional Critical Edition

by Patricia Brauner and Philip Gossett provided the basis for

the staged performance at the Pesaro Rossini Festival in 1987.

This featured Montserrat Caballé as Ermione and Marilyn

Horne as Andromaca. It too was a disaster. Gossett in an excoriating

criticism of both conductor, for lack of preparation, and the

soprano diva for mangling the score (Divas and Scholars.

Chicago 2006 pp 6-7) has continued to maintain the work to be

“One of the finest works in the history of 19thcentury

Italian opera.” Given Gossett’s eminence as

a scholar in this field this is a considerable statement.

After the 1987 Pesaro staging, performances followed elsewhere.

Most significant were those in Rome, San Francisco, and Buenos

Aires as well as at the 1995 and 1996 Glyndebourne Festivals

and all of which involved Anna Caterina Antonacci in the eponymous

role. Her performance in that latter production, along with

an admired cast, is available on DVD (review)

and does much to confirm Gossett’s view as does this present

recording. As to the reason for the initial failure, many have

been suggested. Stendhal, in his famous Life of Rossini

(1824) suggests that the failure was due to the characters spending

much of their time on stage ranting at each other. More likely

is the view of contemporary scholars who, in the context of

Rossini’s operatic oeuvre at the time, view its structure

as several steps too far for the Naples audience of 1819. In

his introductory essay to this issue Jeremy Commons (p.18) states

“Ermione is, quite simply, the most experimental

opera Rossini ever wrote; an opera in which he broke down the

accepted musical structures of the day.”There

are few formal arias or even duets; the chorus or other individuals

often interrupt those that are present. Of those present, notable

are Orestes’ cavatina Reggia abboritta (CD 1 tr.12),

the duet between Orestes and Ermione Amati? Ah si mio ben!

at the start of the act 1 finale (CD 2 trs.2-3) and the duet

between Ermione and Pirro (CD 1 trs.8-10). Perhaps the most

notable however, is Ermione’s recitative Che feci?

Dove son? and the following andantino Parmi che ad ogni

istante (CD 2 tr.20) in the finale to the opera as she regrets

her hasty decision to persuade Orestes to kill Pirro and which

is followed by the dramatic duet with Orestes when she berates

him for not recognising her love for Pirro (tr.21).

Ermione is based on Racine’s Andromaque of 1667,

the first great tragedy of Jean Racine and regarded as a pinnacle

of French drama. The librettist, Leone Tottola, was true to

the origins and there is no attempt at a happy ending as was

often the contemporary practice and expectation. Despite these

factors the score has many of Rossini’s hallmarks of melody

as well as the drama of his opera seria. What any performance

must have, and gets here, is vibrancy and momentum. For this

the conductor, David Parry, deserves the highest praise. To

this must be added the contribution of the chorus who play a

vital role in the evolving drama. The Geoffrey Mitchell Choir,

a presence on many Opera Rara recordings, bring an involvement

and commitment to the performance of the highest standard in

repertoire that will be unknown to them. Add a first class recording

quality and only the accomplishments of the soloists remain

before we can claim an outstanding performance.

The soloists at the premiere and abbreviated run in Naples those

years ago included the redoubtable, if declining in skill, Isabella

Colbran. She was joined by the two famous tenors on the San

Carlo roster, Andrea Nozzari as Pirro and Giovanni David as

Oreste. Both were noted for their formidable techniques; the

former having a somewhat baritonal timbre whilst the latter’s

ability in florid singing was perhaps only surpassed by the

incomparable Rubini. In the Warner recording, Ernesto Palacio,

nowadays famous as the teacher of Juan Diego Florez, can be

recognised by his soft-grained timbre and sensitive phrasing

whilst Chris Merritt, on best vocal behaviour, sings Orestes.

On the basis of the casting in the original Naples performances

I would have expected the roles to be reversed. In this performance

Pirro is sung quite superbly by Paul Nillon who inflects his

singing with passion and more beauty of tone and phrase than

I have often heard from him. Colin Lee, sings Orestes. Lee is

often the back-up to the renowned Florez in the high tessitura

of Rossini performances at the major addresses, perhaps getting

to sing at the end of the run after opening night and the headlines.

Well, that is changing pretty fast with his now being carded

as Tonio for the whole of La Fille du Régiment

at Covent Garden in 2011. He has already featured alongside

Florez in the recent La Donna del Lago in Paris as well

as singing the role of Arturo in the Metropolitan Opera’s

relay of Lucia di Lammermoor, now available on DVD. As

well as having the necessary vocal flexibility, he fields more

body of vocal tone than his Peruvian coeval. This enables him

to invest significant characterisation in his interpretation

without distortion of his singing or vocal line. This quality

is particularly appropriate and appreciated in the act one duet

with Ermione as noted above.

Carmen Giannattasio’s warm soprano scales the vocal challenges

of the role. She conveys Ermione’s various complex emotions

to near perfection. Her singing in the act two finale is of

the highest standard conveying the character’s over-wrought

state prior to her collapse. She does this significantly better

than the leaner-toned Cecilia Gasdia on the rival set; overall

the role fits her like a glove. Certainly her contribution is

the most significant in a generally distinguished group of soloists.

That is not to understate the contribution of the tenors mentioned

or that of the third tenor, Bülent Bezdüz as Pylade.

His timbre is distinct from that of his colleagues whilst conveying

the character well. Graeme Broadbent as Fenicio sings sonorously

in the lower register, more a Zaccaria in waiting; higher up

the scale he is a little less convincing. I greatly admired

Dublin-born Handel specialist Patricia Bardon as Malcolm in

Opera Rara’s recording of La Donna del Lago (see

review).

I find her distinctive low mezzo vocally firm, tonally even

and certainly expressive. Seeing and hearing her as Carmen earlier

this year for Welsh National Opera (see review)

confirmed my impression. If she does not quite manage to reach

the heights of her performance in the earlier Opera Rara Rossini,

recorded live at the Edinburgh festival in 2006, hers is still

a worthy and well-sung interpretation (CD 1 tr.3 and CD 2 trs.10-12).

All the lesser roles are well taken with distinctive vocal qualities

that make following the libretto easy in the various concerted

passages.

The recording is clear and well balanced, far preferable to

the recessed sound on the Warner. Although the Warner performance

is at bargain price the presence of the full libretto and translation

is vital in this opera of complex ensembles. Add the extra ten

or so minutes of music in the Ricordi edition and this recording

and performance is a clear winner. It’s yet another success

for Opera Rara as they work their way through the nine Neapolitan

opera seria.

Robert J Farr

|

|