|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

|

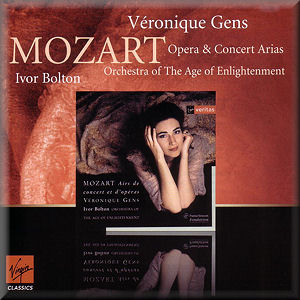

Wolfgang Amadeus

MOZART (1756-1791)

Opera and Concert Arias

La clemenza di Tito (1791):

Deh, per questo istante solo [5:52]

Ecco il punto...Non più di fiori vaghe catene [8:28]

Cosi fan tutte (1790):

Ei parte…Per pietà, ben mio [8:34]

Temerari…Come scoglio [5:40]

Don Giovanni (1787):

Batti, batti, o bel Masetto [3:27]

In quali eccessi…Mi tradì [5:35]

Le nozze di Figaro (1786):

Non so più cosa son [2:34]

Porgi, amor [3:16]

Concert arias:

Ch’io mi scordi di te?...Non temer, amato bene, K505 (1786)

[9:43]

O temerario Arbace!...Per quel paterno amplesso, K79 [6:01]

Véronique Gens (soprano)

Véronique Gens (soprano)

Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment/Ivor Bolton

rec. February/March 1998, Abbey Road Studios, London

VIRGIN CLASSICS 6286332 [59:29]

VIRGIN CLASSICS 6286332 [59:29]

|

|

|

All collectors have, I think, recorded versions of favourite

works to which they remain faithful. When, as a schoolboy, I

first encountered Berlioz’ Les Nuits d’été

- surely one of the most beautiful of all musical works - sung

by Janet Baker and with Barbirolli on the podium, I was hooked.

I learned to appreciate Régine Crespin’s reading,

but Janet had already stolen my heart, and as far as I was concerned

there could never be any rival. Then, some time in 2004, I read

a review of a new performance by French soprano Véronique

Gens and was encouraged to add it to my collection. Now, though

I still revere the earlier performance, when I want to hear

the work it is most likely Véronique that I take down

from the shelves. Hers is quite a different voice from that

of Dame Janet, more brilliant, yet rich and creamy, and just

as beautiful on the ear. And of course she is totally at ease

in the French language, a severe challenge for all but francophone

singers.

Here she is six years or so earlier in a selection of Mozart

arias. One notes that the voice had mellowed somewhat in those

six years: this voice might not so easily have seduced me in

Berlioz. It is a real soprano voice, of course, but there is

no Queen of the Night here. On the contrary, one or two mezzo

roles - and notes - creep in. Thus her Cherubino (from The

Marriage of Figaro) is a passionate and even troubled adolescent,

his amorous preoccupations - at a fairly rapid tempo - more

tortured than breathlessly impetuous. From the same opera, her

Countess is womanly and desirable, touchingly looking back on

what once was.

How subtly she characterises the recitative preceding Donna

Elvira’s superb Act 2 aria from Don Giovanni, “Mi

tradi quell’ alma ingratia”, and how outstandingly

well supported she is by the superb Orchestra of the Age of

Enlightenment and Ivor Bolton. It is the first clarinet who

shines here, but time and again throughout this recital one

is struck by the remarkable quality of the solo wind playing,

without wanting to take anything away from the superbly stylish

unanimity of the strings. And Gens effortlessly negotiates the

runs and leaps, at one point encompassing a low D and top B

flat in successive bars, having chosen just the right tempo

for the music and for her voice. And who could resist her coquettish

seduction technique as Zerlina in the same opera (“Batti,

batti, o bel Masetto”)? Certainly not I. Her way with

the words “baciar, baciar” would be enough for me.

She is equally persuasive in the remaining arias from Cosi

fan tutte and La clemenza di Tito, and the programme

is completed by two concert arias, of which K505 was in composed

in 1786 for the English soprano Nancy Storace. This work features

an important piano part written for the composer himself to

play, taken on this disc by Melvyn Tan.

Recorded recitals of operatic arias tend to be quite popular,

allowing the listener to taste, as it were, the work, without

having to sit through the three hours or so necessary to swallow

the whole. Lovers of Mozart or Véronique Gens need not

hesitate before investing in this one: each of these arias will

bring a little joy and light into anybody’s life, one

after the other, and all at a laughably modest price. One experiences

the operas differently, of course, through extracts such as

these. In the theatre one is struck, usually without thinking

about it, by Mozart’s almost supernatural skill for characterisation

and dramatic pacing. In a succession of arias such as this,

it is the composer’s remarkable melodic gift that comes

to the fore. One gorgeous tune follows another.

The booklet contains an excellent essay by Adélaïde

de Place outlining the context and content of each of the arias

recorded, helpful given that texts are not provided. The recording

is fine.

William Hedley

|

|