|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

MDT

|

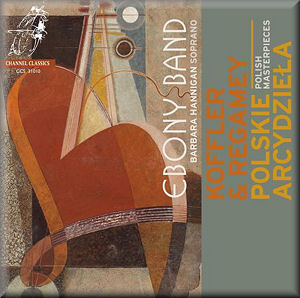

Józef KOFFLER (1896-1944?)

String Trio Op.10 (1928) [16:01]

Die Liebe – Cantata Op.14 (1931) [12:54]

Konstanty REGAMEY (1907-1982)

Quintet for clarinet, bassoon, violin, cello and piano (1942-44) [31:01]

Barbara Hannigan (soprano) (Cantata)

Barbara Hannigan (soprano) (Cantata)

Members of the Ebony Band/Werner Herbers

rec. 3 October 2009, Bachzaal, Amsterdam (Koffler), and live, 17 January 2007, Felix Meritis, Amsterdam (Regamy).

CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS 31010 [60:13]

CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS 31010 [60:13]

|

|

|

Let’s face it, there will always be vast quantities of composers

you’ll never have heard of, and music you’ll probably never

hear – which may never even be performed, ever. It takes the

likes of Werner Herbers, artistic leader of the Ebony Band,

to show us what we’re missing. His energetic search for unjustly

neglected or forgotten composers and their work has been a feature

of the music scene for many years now, bringing obscure but

valuable pieces to vibrant life through the excellent Ebony

Band. This disc is of chamber music, so Herbers is absent as

conductor, but his foreword to the CD outlines his decision

to perform these pieces and describes how Koffler and Regamey

has been received by the players: “never have I seen my musicians

react so enthusiastically and emotionally to music I have placed

before them.” He also asks why these pieces are so rarely heard

– are they too technically demanding, too subtle for our time?

Both of these composers are Polish. Koffler is noted as being

the first and for a long time the only Polish composer to embrace

Schoenbergian 12-note serialism, like Berg, integrating it into

neo-classical and expressionist styles. Koffler was recognised

in his own time, publishing articles and holding respectable

posts, promoting contemporary Polish music and being involved

in the ISCM – his work mostly being performed locally in his

adopted home town of Lvov. Little is known about the fate of

him and his family, and the question mark against his final

year speaks untold volumes. They are thought to have been killed

by the Nazis in 1944 while attempting to find somewhere to hide

beyond Lvov.

The String Trio Op.10 brought the composer international

recognition, and deservedly so. With a classical three movement

structure and a clear sense of counterpoint and thematic development,

much of the actual music reminded me a little of the Beethoven

of the Grosse Fuge but without that particular piece’s

gruff perversities. Like all good string trios, it gives the

sense of wider perspectives than you would expect from just

three instruments, with depth of texture and a good deal of

dynamic layering and interchange. The atonal/serial nature of

the music becomes forgotten in Koffler’s expressive melodic

shapes and phrases – particularly in a beautiful central Andante

(molto cantabile). The musicians here play with absolute

control and intense sensitivity, bringing grace and poetry to

a score which already possesses these qualities, but responds

extremely well to this best of performances.

Die Liebe – Cantata Op.14 uses a biblical text, the 13th

chapter of St. Paul’s epistle to the Corinthians. This is given

in German in the booklet, but without further translation. The

words are invested with the utmost expressive content, the serial

techniques used with a great deal of flexibility, and the piece

has a intensely romantic feel which takes numerous steps away

from more objective feeling vocal scores of Schoenberg. By way

of reference there is a faint whiff of Pierrot Lunaire here

and there, but certainly no sprechstimme, and the vocal

lines and instrumental material falls almost entirely within

what almost could be described a delicate, gently expressive

late romantic idiom. Barbara Hannigan’s singing is perfect,

integrating with the instruments, retaining character without

any kind of overblown histrionics. Words can’t really communicate

the qualities of this music. It always sounds simple, accessible,

moving. What more could you want?

In terms of chronology, Konstanty Ragamy followed Koffler into

use of dodecaphony, with a starting point which aimed at showing

atonality to be a technical device rather than a stylistic choice.

He began composing in earnest during the war years, when concerts

had to be given on a secretive underground basis. Born into

a musical family which was disrupted dramatically but entirely

clandestinely by the Stalinist purges, Regamy rose to prominence

in Warsaw before WWII and became active within the resistance.

After the war he settled in Switzerland, working as an indologist.

Regamey’s Quintet for clarinet, bassoon, violin, cello and

piano has a more extrovert feel compared with Koffler’s

pieces. The Quintet is quite a ‘concerto for soloists’

at times, with equality among the instruments, virtuoso interaction

and plenty of juicy solos. The piece is shaped fairly classically,

with the first movement at over 17 minutes longer than the other

two put together. There are some remarkable effects in this

movement, including some atmospheric trembling, and some remarkable

juxtapositions. After some jocular bassoon-heavy fooling around

the music enters a passage of some of the most expressive chamber

music writing I’ve ever heard, from exactly 10 minutes in to

be precise. This Tema con variazioni is followed by a

slow Intermezzo romantic with long melodic lines and

a dramatic sense of climax. The third movement is a Rondo

(vivace giocoso), which has an exhilarating drive, combining

a Tom and Jerry sense of fun with some serious compositional

development and some weighty musical argument.

As with many ‘Ebony Band’ recordings, there is a live feel to

the performances even where the recordings have been done without

an audience. The Quintet was recorded in Amsterdam’s

remarkable Felix Meritis concert hall, the location which served

as the main venue before the Concertgebouw was built and a location

dripping with a palpable sense of history. There are one or

two very slight extraneous noises in this live recording, but

nothing which takes away from a superlative performance. The

Koffler pieces ooze quality at every level, easily filling the

spacious acoustic of the Bachzaal. This entire programme is

like a gem found amongst the burnt ravages of war and occupation,

in Konstanty Regamy’s case standing as an inspirational landmark

of creativity in times of extreme adversity, all done with no

sense of nationalist fervour or jingoism. It is a tragedy that

so few of Jósef Koffler’s works survive, but both of the pieces

here are more than just a fine memorial. Are these works to

demanding, too subtle? They demand attention certainly, and

are a veritable kaleidoscope of subtle invention, soundly refuting

any preconceived ideas of dodecaphonic unattractiveness. Laurels

to all concerned here for providing us with fabulous new discoveries

way outside the normal repertoire.

Dominy Clements

|

|