|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound

Samples & Downloads

|

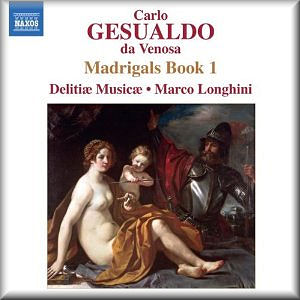

Carlo GESUALDO

da Venosa (1566-1613)

Madrigals - Book 1

Delitiae Musicae (Alessandro Carmignani, Paolo Costa (alto), Fabio

Fùrnari, Paolo Fanciulacci (tenor), Marco Scavazza (baritone), Walter

Testolin (bass), Carmen Leoni (harpsichord)*)/Marco Longhini

Delitiae Musicae (Alessandro Carmignani, Paolo Costa (alto), Fabio

Fùrnari, Paolo Fanciulacci (tenor), Marco Scavazza (baritone), Walter

Testolin (bass), Carmen Leoni (harpsichord)*)/Marco Longhini

rec. 23-27 July 2007, Chiesa di San Pietro in Vincoli, Azzago, Verona,

Italy. DDD

NAXOS 8.570548 [56:15]

NAXOS 8.570548 [56:15]

|

|

|

Baci soavi e cari (1. Parte) [3:36]

Quanto ha di dolce amore (2. Parte) [3:15]

Madonna, io ben vorrei [3:35]

Come esser può ch'io viva? [2:41]

Gelo ha madonna il seno [2:39]

Mentre madonna (1. Parte) [2:39]

Ahi, troppo saggia (2. Parte) [2:56]

Se da si nobil mano [2:24]

Amor, pace non chero* [2:03]

Si gioioso mi fanno il dolor miei [3:32]

O dolce mio martire [2:39]

Tirsi morir volea (1. Parte) [3:21]

Frenò Tirsi il desio (2. Parte) [2:46]

Mentre, mia stella, miri [2:56]

Non mirar, non mirare [3:08]

Questi leggiadri odorosetti fiori [3:37]

Felice primavera! (1. Parte)* [2:11]

Danzan le ninfe (2. Parte)* [1:33]

Son sì belle le rose [2:31]

Bella angioletta [2:13]

Few composers have so fascinated the music world as Carlo Gesualdo

da Venosa. Part of the interest has been generated by his remarkable

life, especially the fact that he once murdered his wife and

her lover. Musically speaking the madrigals he composed in the

latter stages of his life have drawn the interest of performers

and audiences as well as composers of a much later era. Among

the latter is Igor Stravinsky who composed a Monumentum pro

Gesualdo di Venosa, based on three of his madrigals. The

late madrigals are collected in the fifth and sixth book, and

move far away from the musical mainstream of his time. Until

the end of his life Gesualdo stayed away from the seconda

prattica and the use of a basso continuo. In his application

of dissonances and chromaticism he goes further than any composer

of his time.

In comparison his early madrigals are much more moderate and

conventional. That is probably the main reason they haven't

received as much attention as the later works. The first two

madrigal books were published in the same year: 1594. They were

presented as a compilation Gesualdo had published previously.

Unfortunately none of these have been preserved. So it is impossible

to assess how exactly Gesualdo has developed. The first two

books certainly don't present him as a student. These are mature

works in which the texts are effectively expressed with the

musical means of the time. Although there are some dissonances

in a number of madrigals, Gesualdo doesn't go to extremes in

regard to harmony as in his later madrigals.

In the first book he uses texts by famous poets, like Giovanni

Battista Guarini and Torquato Tasso. Several of these were also

set to music by other composers of his time, for instance Claudio

Monteverdi and Luca Marenzio. Gesualdo seems to have had a special

liking for gloomy subjects. That is not only reflected in his

madrigals, but also in his motets. It is notable, though, that

the first book ends with five madrigals of a more joyful character.

The titles are telling: Bella angioletta (Beautiful little

angel), Felice primavera! (Happy Spring!) and Danzan

le ninfe oneste (The honest nymphs and shepherds dance).

Compare these with titles of madrigals like Come esser può

ch'io viva (How can it be that I live), O dolce mio martire

(O sweet torment of mine) or Gelo ha madonna il seno

(My lady has ice in her breast).

After having completed the recording of the madrigals of Claudio

Monteverdi the ensemble Delitiae Musicae have started a project

to record all six books of madrigals by Gesualdo. Marco Longhini's

interpretation is quite unusual in several respects. To begin

with, he consistently uses only male voices in his madrigal

recordings. This means that the male alto Alessandro Carmignani

who takes the upper part has to sing at the top of his range

most of the time. He manages to do so quite well, but now and

then his voice does sound a little stressed.

Historically this practice may be defensible, two other features

of this interpretation are questionable. Firstly, the frequent

tempo fluctuations which are often extreme and sound unnatural

to my ears. At the last line of the first madrigal, Baci

soavi e cari, the music almost comes to a standstill. Secondly,

the use of crescendi and diminuendi. This is an interpretational

device which rather belongs to the seconda prattica which

was introduced in the early 17th century. But in these madrigals

it seems hardly appropriate.

In three of the madrigals the harpsichord plays colla voce.

I don't understand the reasoning behind this practice nor do

I understand why it is used in these particular madrigals. Musically

it is unsatisfying and damages the performance. In several madrigals

the last line has to be repeated, and the ensemble takes mostly

too long a pause before doing so. This becomes a bit annoying

after a while. It is probably meant to increase the drama, but

it doesn't.

It is these mannerisms that raise my scepticism about this new

recording. The singers of Delitiae Musicae are excellent, and

I certainly have enjoyed much of what they do. But there are

just too many questionable aspects, and because of that I can

only approach this disc with considerable caution.

Johan van Veen

see also

Don

Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa, Count of Conza (1561†

- 1613) by Len Mullenger

|

|