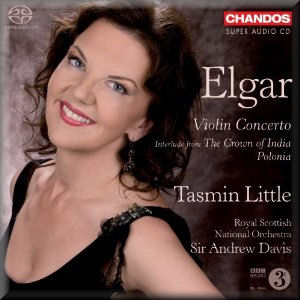

Tasmin Little records the Elgar Violin

Concerto - an interview with Nick Barnard

With the

major release of a long-awaited recording from one of Britain’s

best-loved and finest violinists imminent, Tasmin Little very

kindly found an hour in her busy schedule to talk about this important

new disc … and other things

Nick Barnard [NB]: In researching this interview it amazed

me to realise that it is now some twenty-one years since your

breakthrough recording.

Tasmin Little [TL]: Yes, absolutely which was the Bruch

and the Dvorák for EMI. I recorded it in 1989 and it was released

in 1990, the same year I made my debut at the Proms. So 1990 is

probably the year that I consider that my career began. The Prom

was the Janácek concerto – it had only recently been discovered

and was a Proms premiere. Because it was a curiosity and my debut

I got an enormous amount of publicity which was wonderful. That

coupled with the release of the Bruch and Dvorák disc which got

tremendous reviews … it really set me on the right path as it

were. After which the recordings came in fairly thick and fast

including the Delius Violin Concerto and Double Concerto.

NB: But before this new disc of the Elgar concerto there

has been a gap of about seven years since your last concerto disc

– the Moszkowski?

TL: That’s right, with the Karlowicz. Since then I began

my naked violin project and also released the follow-up CD Partners

in time. I had been wanting to record the Elgar for many many

years and had had in fact many offers to do it. Quite a few early

on when I was making my way. I really felt it wasn’t the right

timing; the Elgar for me was a piece I needed to live with and

grow into. Not that my performances weren’t valid then, I’m sure

they were very fine but I think they would have been ‘young Tasmin’

kind of performances. Now I’ve had so much experience of playing

that piece – 20 years, more actually, and worked with so many

tremendous conductors and also lived since then! I do feel it

is a piece that requires you to have the sense of occasion, of

wonder and awe for this monumental work as well as quite an experienced

head on your shoulders. Not just with regard to playing the piece

but also to life. He was not a young man when he wrote the violin

concerto – it’s a piece of someone who had also lived so I feel

you need to be able to associate with some of that.

NB: Was it a work you studied at the Menuhin School or

the Guildhall School of Music?

TL: No it was after I came back from private studies in

Canada, the RPO asked me to play it with Yan Pascal Tortelier.

They gave me quite a lot of notice which was jolly good because

I certainly needed it – I think I had about six months which at

that point in time I hardly had anything else to do and it was

one of the first things that I did starting out as a fully-fledged

professional.

NB: I was surprised to realise that it was the first time

Chandos have recorded it as well.

TL: It is quite a surprising thing isn’t it. Perhaps they

felt much as I did that the perfect set of circumstances had to

come together in order to make the recording which was certainly

how I felt. I’m incredibly glad that I listened to my instinct

to wait to make the recording that I believe I have made and the

one that I really am sure I will listen to in the years to come

and be incredibly proud of.

NB: The Elgar seems to have had a recent burst of recording

popularity. What is it in Elgar that is so currently appealing

to a crop of young non-British violinists?

TL: When I was growing up the Elgar was not particularly

well known. Then there was the ‘batch’ of Zuckerman, Perlman and

the like. That was the era that set the seal on the popularity

of the concerto because it had been relatively neglected up until

that point. Perhaps the current group of recordings comes from

the generation of violinists who have grown up after that group

of recordings and now feel ready to record the work.

NB: One of your other great loves is Delius; why is it

do you think that his music resolutely refuses to enter the mainstream

repertoire or indeed be promoted by many players?

TL: I’m sure there are two aspects which are perhaps joined.

The one is that there is not an enormous call for it therefore

orchestras and soloists are reluctant to spend time learning it

but then it’s a case of the chicken and the egg where if the works

are not programmed how will audiences get to the stage where they

know they like it. Another reason is because as far as a soloist

is concerned you have to be a particular kind of temperament -

to not mind not having the ‘whizz-bang’ ending. Because, almost

without exception, the major works of Delius end quietly and that’s

not the circumstance that’s going to elicit rapturous applause.

If you are looking to create a sensation Delius’ music is not

going to provide that. Its much easier to turn to concertos that

are obviously difficult where people will feel that you worked

very hard, you did an amazing job and they’ll reward you with

lots of applause. The Delius [concerto] is incredibly hard and

yet it doesn’t

sound hard. For some people that’s not going

to be any good. A lot of soloists do like to feel that the audience

is aware of the difficulty and therefore be impressed by that.

We have 2012 coming up [the 150

th anniversary of his

birth] and I’m really hoping there will be an opportunity for

people to experience a wider range of Delius’ music.

NB: I read on your website that you feel performing live

has the highest priority with recording slightly lower down the

list. But if it

weren’t for your recordings of the Delius

and Rubbra concertos to name but two we as willing concert goers

would not have had the chance to hear the music let alone hear

you playing them.

TL: Recordings are extremely important to me. I plan and

hope to continue making recordings. But at the end of the day

I really think there needs to be a reason to record something

and it goes back to what I was saying earlier abut the right circumstances;

the right team, the right record company, the right repertoire

all have to come together. I don’t believe in making a recording

because somebody says “I’ve got a free date here, we could put

that together pretty quickly”. That is so far from my ethos and

so that was probably why I had a little bit of a gap as far as

concerto recordings were concerned. There are too many recordings

out there now; if I’m going to make my version its got to be the

best version that I can make. Which is why I feel so happy about

the Elgar Concerto. Not only do I feel that I was absolutely at

the top of my game but everybody else was too. I’m sure that that

makes itself felt – I hope it does. I feel that there is so much

spontaneity, so much excitement, so much commitment on this recording

and that’s what I want – its absolutely imperative to me

NB: In the recording environment the demands seems to be

not for the danger, risk or spontaneity of live performance but

instead a kind of superhuman perfection.

TL: Yes, and that is a huge danger in making a recording.

Obviously you don’t want to have mistakes glaring out at you but

you can go completely the other way and get so ridiculously worried

abut every single note. Whereas in fact it is the sweep of the

music, the performance itself that will make people come along.

Which is one of the reasons I always liked to work in large takes.

To play complete movements of the piece and to really get that

sense of performance before starting the nit-picking. Of course

when you hear your first edit when everything is put together

I think it is incredibly important to let yourself be carried

away by the music. After that you can listen again to see if there

is anything that jumps out as not being what I wanted. On the

Elgar recording I had extraordinarily few comments. On a piece

that lasts fifty minutes I had ten comments to make. You hear

sometimes of artists who come back with five hundred ‘corrections’

– sometimes of just one tiny note. I will say my Elgar is

not

completely perfect but I think it can’t be better than it

is. Because if there is one note that might have just been a tiny

bit sharp or a tiny bit flat I’m prepared to let that go in the

vast sweep of the atmosphere that I believe I was able to create

alongside Andrew Davis and the orchestra. For me its much more

about ‘is the shape of that phrase exactly what I hoped to create’

and I can really put my hand on my heart and say that on this

recording the shape of the phrases, the colour of my sound, the

atmosphere and the sweep of the piece is exactly what I wanted.

NB: Which violin did you use on the recording? [Tasmin

plays a 1757

Guadagnini violin and

has, on loan from the

Royal

Academy of Music, the 1708 "Regent"

Stradivarius]

TL: The Guadagnini. It’s the Strad I often use in performance

because the nature of concertos in big venues is that that suits

the Strad which has the awesome carrying power my Guadagnini doesn’t

have. What the Guadagnini does have is a superb ability to shine

in recordings because it has so many colours available and a really

velvet sound that comes over superbly on disc. Most of the concerto

recordings have used the Guadagnini although I used the Strad

on the Moszkowski/

Karlowicz disc. On the ‘Naked Violin’

and ‘Partners in Time’ recordings you have the opportunity to

experience both

NB: Obviously the – awful phrase – ‘Unique Selling Point’

of your Elgar is the Marie Hall Cadenza. How genuinely valid do

feel this is?

TL: I think that its completely valid in terms of an historical

document . I probably wouldn’t think of replacing the actual cadenza

with that version of it but what I think it does provide people

with is the opportunity first of all to hear how effectively Elgar

brought the harp into a piece that hasn’t got a harp. I don’t

think it suddenly sounds like another world at all. From the point

of view of just adding an extra colour to the atmosphere that’s

created by the thrummed strings I do think its interesting to

hear it. I really love the way it becomes a more glowingly romantic

version of the cadenza.

NB: Doesn’t the harp sentimentalise the gentle reflective

nostalgia of the original?

TL: It does sentimentalise it and I agree that that’s why

I don’t think it would be appropriate to replace the existing

cadenza in a normal performance. But I do like it, I really do.

I love the different colour and its interesting to hear it that

way in exactly the same way it was interesting to hear the Sibelius

Violin Concerto in its original form. I wouldn’t dream of playing

the Sibelius that way but to hear the original you can understand

why it was that he then decided to revise but it is fascinating

to hear what he thought was ‘right’ at that time. I think there

will be plenty of people who will be enthralled to hear how Elgar

solved what was a very real problem in the early days of recording.

It is a pragmatic approach but there is one bit where I think

he gets rather carried away and enjoys having his harp there;

there is quite a ‘declaration’ from me and although it is quite

unnecessary to have anything else at that point he decides to

emphasise my declaration with a harp chord.

NB: How important or significant to

Elgar or listeners

and performers is a comprehension of the dedication of the concerto

“herein lies enshrined the soul of *****”

TL: It helps but is not absolutely essential. If somebody

understands music they just understand it without necessarily

knowing what it is that has caused the feeling. When I first heard

the Elgar performed live when I was about 19 or 20 I was a poor

student. So I didn’t have a programme so I did not know anything

at all about the extraordinary placing of the cadenza or the idea

of the soul enshrined. But I absolutely knew that there was a

journey there, a spiritual searching and I had an innate understanding

of the work without knowing exactly why it was written as it was.

NB: When playing this piece do you have a non-musical narrative

that you are following?

TL: It’s a curious thing; when I was first preparing the

Delius Concerto I did have a kind of narrative going on. I do

that less and less now but instead I think more and more now in

terms of colours and characters. So, I can often find an adjective

that will describe what I am aiming to do with one particular

passage of a work. So whether it is ‘restless’ or ‘turbulent’

or ‘peaceful’, ‘joyous’ I can very often sum it up like that but

I won’t create a storyline.

NB: So who do you think the ***** are?

TL: I think it must be Alice Stewart-Wortley. He was so

blocked trying to write this piece and it was her urging him on.

He writes things in letters “this is

your concerto”, “the

windflower theme is coming on well”. We know that the soul is

a feminine one. Elgar was so fond of his enigmas. Perhaps he was

a good businessman too and he knew it would keep everyone talking

a hundred later – and it has!

NB: Do British audiences have the opportunity to hear you

playing the Elgar live in the near future?

TL: Yes, but I’m not allowed to say! All of my concerts

are listed on my website [http://www.tasminlittle.org.uk/pages/02_pages/02_set_concerts]

and as soon as I can the information will be there.

NB: Are there any plans for any more recordings?

TL: I have just recorded something else for Chandos that

is rather wonderful and major and there are plans for more next

year but at the moment the details of exactly what will have to

stay hush-hush. It is scheduled for a 2011 release with a very

similar creative team to the Elgar.

NB: If I was able to wave a magic wand and make any project

possible what would you like to do?

TL: Oh my goodness

, that’s very hard because

the nice thing is there’s always lots more to do so pinning myself

down to one is tricky. I’d love to play the Brahms in the Carnegie

Hall with Simon Rattle and either the New York Phil or the Berlin

Phil. I have played in the Carnegie Hall with Simon and it was

an absolute highlight – I played the Ligeti and I have done the

Brahms with Simon and that was another highlight of my career

so to put the Brahms in the Carnegie Hall with Simon would be

wonderful.

NB: Is there a particular piece that you feel cries out

for rehabilitation that you feel promoters won’t risk programming?

TL: There’s quite a few actually, I still think that even

the Walton concerto doesn’t get quite the attention that it should.

The Karlowicz which I recorded is a superb piece and definitely

should be played more often. I’ve just been playing the Howard

Ferguson 2

nd Sonata which is absolutely divine.

NB: I saw on your website that you named Ida Haendel as

one of your violin heroes – why?

TL: first of all because she was someone who was playing

all sorts of repertoire – a lot of it British – when no-one else

was. Ida Haendel was playing the Britten Violin Concerto when

no-one else did. She also played the Elgar, Walton and Delius.

I love the fact that she was an incredibly strong woman. So as

a strong passionate characterful woman violinist she was a great

role model for me and someone I aspired to being like. And I loved

her ability to hold a long musical line. For example nobody plays

the second movement of the Sibelius concerto like Ida Haendel

– this is the recording [Haendel/Berglund/Bournemouth SO] that

turned me onto the Sibelius. No-one else had managed to make it

work for me emotionally before her – and this was when I was very

young.

NB: One last question

- of your back catalogue what

recording are you proudest of?

TL: That’s a very good question. When

you make a

recording it’s a snap-shot in time of how you were then and so

quite often when I listen – which I don’t with terrible regularity

– to recordings I have made I often feel oh gosh yes wasn’t I

young then but I would play it very differently now. I think my

Sibelius concerto is still very good indeed as is my Bruch Scottish

Fantasy and all the Delius Sonatas which I think is a record I

think I will always listen to and be very proud of.

Nick Barnard