|

|

|

Availability

CD or Download:

Pristine Audio

|

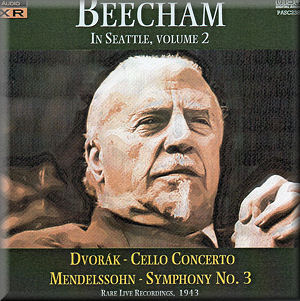

Beecham in Seattle - Volume 2

Antonín DVORÁK

(1841 – 1904)

Cello Concerto in B minor, op.104 (1895) [42:04]

Felix MENDELSSOHN

(1809–1949) Symphony No.3 in A minor, Scottish,

op.56 (1842) [35:17]

Mischel Cherniavsky (cello)

Mischel Cherniavsky (cello)

Seattle Symphony Orchestra/Sir Thomas Beecham

rec. 11 (Mendelssohn) and 18 October 1943 (Dvorák), Music Hall Theatre,

Seattle WA, ADD

PRISTINE AUDIO PASC 238 [77:21]

PRISTINE AUDIO PASC 238 [77:21]

|

|

|

I welcome any historical re–issue for they shed light on performance

techniques and attitudes, as well as giving those of us who

never heard the performers in the flesh a chance to experience

artists we have only ever read about and heard in the recording

studio. Live music-making is such a different experience to

making records that the work that Pristine Audio has done –

bringing to our attention so many performances of historical

importance – can only be praised for it is invaluable to anyone

interested in the art of performance and interpretation.

Another aspect of the live performance is when you get two artists

who may not see eye to eye on how to perform a work. There is

also the chance to hear pieces which the performers seldom gave,

and never recorded commercially. And here we come to the Dvorák

Cello Concerto on this disk. This is an odd performance

indeed. I suspect that Beecham is having a good time but I cannot

believe that he was happy with this performance. The opening

tutti begins in a very exciting and forthright manner,

but the beautiful second theme is ruined by a very lazy horn

soloist, not to mention the application of the brakes to the

established tempo. Things pick up again in the lead to the entry

of the soloist but although Cherniavsky shows great strength

in his opening phrases he lacks real impetus, pulling the tempo

back, then racing off until he reaches a section he can’t possibly

manage at the tempo he has chosen so on go the brakes again.

Ensemble is occasionally poor, intonation leaves a bit to be

desired and bar 175 gains an extra beat! The recording ends

14 bars from the end of the movement. The other movements are

better but the music is pulled about far too much, and Cherniavsky’s

portamento becomes tiring to the ear. This really is

for study only because I cannot imagine anyone, not even the

most ardent Beecham fan – and I am one of them – wanting to

spend too much time with this performance.

The Mendelssohn Symphony is a totally different matter

– it’s hard to believe that this is the same orchestra, let

alone the same orchestra only a week earlier! There is a virility

to this performance, a momentum which is missing from the Concerto.

Perhaps Beecham felt constrained by the soloist. The first movement

is admirably forthright, and Beecham adopts a cracking tempo.

Unfortunately, at 12:02 there is a section of the music missing.

The scherzo also has a good tempo and the music races along

in high spirits. But at 2:15 there’s a section missing. The

slow movement is full of atmosphere and Beecham refuses to linger

and look at the scenery for there is more to come. The finale

is very enjoyable, perhaps slightly too fast but there’s bags

of excitement and drama. What is missing, and it’s one of the

many things which mar the Concerto, is an almost total

lack of rubato, and when Beecham employs it it’s so subtle as

to be almost unnoticeable. Nothing here is exaggerated or over-played.

One couldn’t claim that, at the time of these performances,

the Seattle Symphony was a particularly good orchestra: ensemble

and intonation is suspect, and parts of the performance are

very rough and ready. But, when left to his own devices, Beecham

gets a good result from them, and the Mendelssohn Symphony

makes one lament that he never made a commercial recording of

this work.

Whilst I cannot warm to the performance of the Dvorak Concerto,

the Mendelssohn is a must-have. The sound is very good, the

acetates used being Beecham’s own, and although there is some

stridency in climaxes it’s not so much as to annoy or spoil

your enjoyment.

Bob Briggs

|

|