|

|

|

alternatively

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

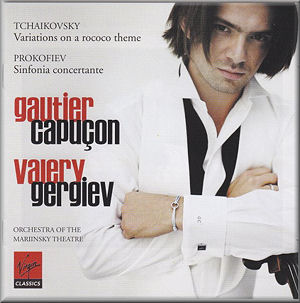

Sergei PROKOFIEV (1891-1953)

Sinfonia Concertante (Symphony-Concerto) for

cello and orchestra in E minor, Op. 125 (1951/52) [41:40]

Pyotr Ilyich TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893)

Variations on a Rococo Theme, for cello and orchestra in

A major, Op. 33 (1876) [19:26]

Gautier Capuçon (cello)

Gautier Capuçon (cello)

Orchestra of the Mariinsky Theatre/Valery Gergiev

rec. live, 24 December 2008, Concert Hall of the Mariinsky Theatre,

St Petersburg, Russia. DDD

VIRGIN CLASSICS 50999 694486 0 7 [61:19]

VIRGIN CLASSICS 50999 694486 0 7 [61:19]

|

|

alternatively

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

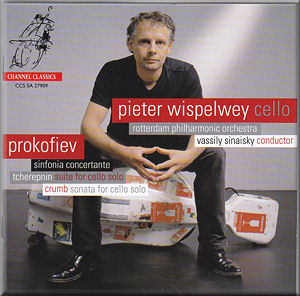

Sergei PROKOFIEV (1891-1953)

Sinfonia Concertante (Symphony-Concerto) for

cello and orchestra in E minor, Op. 125 (1951/52) [40:04]

Alexander TCHEREPNIN (1899-1977)

Suite for cello solo, Op. 76 (1946) [6:55]

George CRUMB (b. 1929)

Sonata for solo cello (1955) [11:09]

Pieter Wispelwey (cello)

Pieter Wispelwey (cello)

Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra/Vassily Sinaisky

rec. live, November 2007, De Doelen, Rotterdam, Holland (Prokofiev);

December 2008, Doopsgezinde kerk, Deventer, Holland (Tcherepnin,

Crumb). DDD

CHANNEL CLASSICS

CHANNEL CLASSICS  CCS

SA 27909 [59:45] CCS

SA 27909 [59:45]

|

|

|

These are interesting and most rewarding releases featuring Prokofiev’s

substantial Symphony-Concerto - a masterwork that deserves

to be far wider known. The Virgin Classics release contains both

Prokofiev and Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations; works separated

by over seventy years. The extremely popular Rococo Variations

is frequently performed probably at the expense of the Sinfonia

Concertante, a score that suffers from a comparative

and unwarranted neglect in concert programmes. The virtuoso demands

on the soloist in the Prokofiev, especially in the central

movement, make this one of the most challenging scores in the

cello repertoire.

The blend of French cellist Gautier Capuçon, the Mariinsky Theatre

Orchestra and their maverick Russian-born conductor Valery Gergiev

is a heady and exciting prospect. Capuçon has quickly built himself

a reputation for communicating significant passion in the late-Romantic

repertoire. Whilst the amazingly hard-working Maestro Gergiev

is also renowned for interpretations of real dramatic intensity.

Capuçon plays either a Matteo Goffriler cello from 1701 or a Joseph

Contreras from 1746. I’m not sure which he was using for this

live 2008 Christmas Eve recording at the Mariinsky but I was struck

by the instrument’s rich, mellow and velvety timbre.

Pieter Wispelwey in his Channel Classics release plays his usual

1760 Giovanni Battista Guadagnini cello and is supported in the

Prokofiev by Sinaisky and the Rotterdam Philharmonic. Wispelwey’s

couplings are for solo cello. I have been eagerly anticipating

this release since I saw the disc back in September 2009 displayed

in the music department of the famous department store Ludwig

Beck in the Marienplatz, Munich.

The Prokofiev work has a convoluted history and started out as

a cello concerto. Encouraged by cellist Gregor Piatigorsky Prokofiev

made sketches for his Cello Concerto No. 1 in E major,

Op. 58 as early as 1933. The score was introduced in 1938 at Moscow

by another cellist Lev Berezovsky and the USSR State Symphony

Orchestra under Alexander Melik-Pashayev. Poorly received, Prokofiev

felt the score needed alteration and he set about extensive rewriting.

At Boston in 1940 Piatigorsky gave the American première of the

score in its revised form. Some years later in 1947 Prokofiev

attended another performance of the neglected concerto given by

cellist Mstislav Rostropovich at the Moscow Conservatoire. Rostropovich’s

playing sparked Prokofiev’s fresh interest in the score and with

assistance from the great cellist in 1950-52 he undertook yet

more revisions. At the 1952 introduction of what was briefly known

as his Cello Concerto No. 2 Rostropovich was the soloist

under Sviatoslav Richter. Renowned pianist Richter was making

his rather unlikely conducting debut with the Moscow Youth Orchestra;

seemingly his only public attempt at conducting. Prokofiev made

additional revisions recasting the score as his Sinfonia Concertante

for cello and orchestra in E minor, Op. 125. Incidentally

the score is sometimes known as the Symphony-Concerto.

It was after Prokofiev’s death that the Sinfonia Concertante

was given its première in 1954 by Rostropovich with the Danish

Radio Orchestra at concert at Copenhagen.

The opening movement of the Sinfonia Concertante the Andante

contains predominantly dusky tones of a nocturnal character.

I loved the thoughtful and ultra-moody playing from Capuçon. I

noticed on the Channel Classics performance that Sinaisky underlines

the martial character of the movement splendidly. His soloist

Wispelwey remains poised and in total control throughout without

wringing out as much emotion as Capuçon.

I enjoyed Prokofiev’s opening pages of the extended middle movement

marked Allegro giusto. They have a mocking and rather in-your-face

character together with wonderfully varied orchestral support.

Both Capuçon and Wispelwey exude an air of joy and carefree frolic.

Capuçon from 3:25 and Wispelwey at 3:21 convey a remarkable outpouring

of melancholy and bleakness with a conspicuous undercurrent of

tension. With Capuçon at 7:14 and Wispelwey from 7:28 the mood

changes abruptly to one of stabbing anxiety and anguish. The movement

closes in an agitated mood of gathering pace and potent energy.

The wide-ranging rhythms and dynamics of the closing movement

Andante con moto provide fascinating textures. These are

often witty, sinister and nervy; they border on the exotic. One

senses that both Capuçon and Wispelwey are incredibly at one with

this wonderful expressive music. The score’s conclusion is a riotous

torrent of an almost grotesque quality. Clearly Prokofiev’s magnificent

and rewarding music does not reveal its treasures immediately

and the listener will undoubtedly be rewarded by repeated listening.

Wispelwey is excellent with his innate capacity for securing firm

and secure control and sensitive expression fully evident. By

contrast Capuçon is the more intense performer wearing his heart

on his sleeve. Capuçon’s reading is warmly exuberant and incontestably

spontaneous; an approach that is more to my taste in this music

than that of Wispelwey. Both soloists have the benefit of glorious

orchestral accompaniment from their committed conductors.

Capuçon has the advantage of warm and crystal-clear sound. Closely

recorded, the woodwind are a touch bright but I marvelled at the

wonderful tone of Capuçon’s cello. Wispelwey has the benefit of

cool, clear and well balanced sound. I played this Channel Classics

hybrid SACD on my standard equipment.

Despite its comparative neglect in the concert hall there have

been several fine recordings of the Prokofiev. The most

notable is from Rostropovich with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

under Sir Malcolm Sargent on EMI; Raphael Wallfisch with the Royal

Scottish National Orchestra under Neeme Järvi on Chandos; Han-Na

Chang with the London Symphony Orchestra under Antonio Pappano

on EMI; Lynn Harrell with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra under

Vladimir Ashkenazy on Decca and Yo-Yo Ma with the Pittsburgh Symphony

Orchestra under Lorin Maazel on Sony. These accounts from Capuçon

and Wispelwey can rub shoulders with the finest. I believe that

the reading from Capuçon is very special and deserves considerable

praise.

Tchaikovsky wrote his Variations on a Rococo Theme in

1876 for Wilhelm Fitzenhagen, a German cellist and fellow professor

at the Moscow Conservatoire. The appealing score comprises a theme

and a set of seven variations with coda. In this live performance

Capuçon plays Wilhelm Fitzenhagen’s revised version of Tchaikovsky’s

score as published in 1878. The main theme first heard at 0:58

is beautifully underlined by Capuçon who plays throughout with

insatiable affection, vitality and control. I especially enjoyed

the second variation where the cello and orchestra undertake a

short but lively discussion. In variation three I was struck by

the impassioned tenderness of the soloist in his long and attractive

cello line. Capuçon provides an amiable and distinctly mischievous

character to variation five and in the score’s conclusion I loved

the wild, bold and infectiously spirited folk-dance. Despite the

Capuçon I still have a strong affection for the memorable 1968

Berlin account from Rostropovich and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

under Karajan. Rostropovich’s coupling from the same Berlin recording

session at the Jesus Christ Church, Dahlem is his legendary interpretation

of the Dvorák Cello Concerto. Quite rightly the disc has

achieved classic status and has been issued many times over the

years. My copy is on Deutsche Grammophon 447 413-2.

To serve as encores Pieter Wispelwey on his Channel Classics release

performs a short score for solo cello each by Alexander Tcherepnin

and George Crumb. Both works were recorded in 2008 at the Doopsgezinde

kerk in Deventer. They profit from vividly clear sound quality.

Described by Willi Reich as a “musical citizen of the world”

the St. Petersburg-born Tcherepnin spent much of his life in America,

maintaining links with Paris for fifty years. Tcherepnin clearly

admired the cello and published ten or so scores that feature

the instrument. Composed in 1946 his Sonata for solo cello

is a short four movement work lasting just under seven minutes.

The opening movement Quasi Cadenza is a yearning song mainly

demonstrating the mid-range of the instrument. Vivacious and dance-infused,

the untitled second movement contains some fascinating effects.

I was reminded of a tired-sounding barrel organ with the slow

and languorous untitled third movement. The score concludes with

a brisk and spirited Vivace. Again there are some interesting

effects. Sadly the Channel Classics notes say virtually nothing

about the Sonata which comes across as absorbing, varied

and virtuosic.

American composer, George Crumb is one of the most played of contemporary

composers. His best known work is Black Angels for electric

string quartet, completed in 1970. Crumb composed his three movement

Sonata for solo cello in 1955 during his time studying

with Boris Blacher in Berlin. Movement one marked Fantasia:

Andante espressivo e con molto rubato includes the use of

pizzicato chords. Its yearning cry evokes an almost world-weary

mood. The character becomes increasingly melancholy and bleak.

Divided into four tracks, movement two marked Tema pastorale

con variazioni, contains a decidedly chromatic theme

with three variations and a coda. The final movement Toccata:

Largo e drammatico - Allegro vivace just bursts onto the

scene with dark drama and considerable energy. Wispelwey plays

both the Tcherepnin and Crumb with an artistry that is high on

concentration and with exacting precision.

Michael Cookson

|

|