|

|

|

alternatively

CD: Crotchet

|

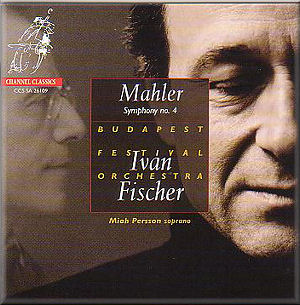

Gustav MAHLER (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 4 in G major (1892, 1899-1900; revised 1910)

I. Bedächtig, nicht eilen [16:51]

II. In gemächlicher Bewegung, ohne Hast [9:26]

III. Ruhevolle, poco adagio [21:51]

IV. Sehr behaglich [8:32]

Miah Persson (soprano)

Miah Persson (soprano)

Budapest Festival Orchestra/Iván Fischer

rec. Palace of Arts, Budapest, Hungary, September 2008

Text and translation of the last movement included

CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 26109

CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 26109  [57:00]

[57:00]

|

|

|

I have heard a large number of recordings of this symphony over

the years and was fortunate to attend one of Leonard Bernstein’s

concerts with the New York Philharmonic with Jeannette Zarou

as soprano soloist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor

in September 1967. Bernstein’s first recording with Reri

Grist was my introduction to the symphony. From that time on

this work has been one of my favorites. In addition to that

recording, I have greatly admired those of George Szell with

Judith Raskin, Jascha Horenstein with Margaret Price, and Lorin

Maazel with Kathleen Battle, among others. I refer the reader

to Tony Duggan’s MusicWeb International survey of this

symphony for his recommendations among the many alternatives.

Having listened to this new recording by Iván Fischer

several times on different systems, but unfortunately on only

two channels, I would without hesitation place it at the very

top of the list. It is that good! This is largely because it

sounds so natural. Fischer has developed his orchestra into

a world-class ensemble with rich but luminous strings and wonderful

winds. The recording balances everything with perfection and

nothing sounds in the least bit contrived, but the symphony

comes up fresh minted - an over-used phrase, but pertinent here.

Fischer convinces as a real Mahlerian, with a judicious but

very natural employment of rubato. It is interesting that while

he seems so well suited to Mahler, his recording of Brahms First

Symphony that I also reviewed for this website, falls short

for that very reason. There the rubato feels imposed, applied

from the outside, while here it is part and parcel of the work.

He obviously has a greater affinity for Mahler than for Brahms.

He is also meticulous when it comes to following the score and

observing the dynamics.

My reference recording of this symphony on CD has been until

now Lorin Maazel’s and the Vienna Philharmonic, with Kathleen

Battle singing the “Das himmlische Leben” song of

the last movement on Sony, for its combination of radiant performance

and warm, present sound. Now in direct comparison with the present

disc, I find Maazel just a bit too mannered and Battle’s

child-like voice rather affected-especially the stanza beginning

with “Kein musik ist ja nicht auf Erden.” It is

interesting that Maazel is slower in all four movements, though

barely so in the second: Maazel’s timings are: I- 18:03,

II- 9:28, III- 22:31, IV- 10:41 (see the timings for Fischer

above). The biggest difference is in the finale, which seems

very slow, though Szell took a similar tempo in his recording.

The one movement where Maazel really scores, however, is the

second movement scherzo, which he characterizes extremely

well by bringing out the darker elements in the music. Perhaps

Fischer is smoother and somewhat less characterful in comparison,

but still detailed and idiomatic. In the other movements he

is unbeatable. The playing of his Budapest orchestra is above

reproach with particularly beautiful winds, especially the oboe

and horn parts. Check out the oboe, for example, about five

minutes into the third movement. The whole movement is gorgeous,

with especial attention paid to the dynamics. Then, the finale

is best of all. Miah Persson captures the innocence of the child

without sounding childish or too sweet, just very natural and

joyful. Listening to Raskin for Szell or Price for Horenstein

here is enlightening. Both sound too mature, if not matronly,

though good in their own ways. Then there is the disaster of

Bernstein using an actual boy for his solo in his later version

with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. It might have been a good

idea in theory, but it just doesn’t work. Mahler intended

the song to be sung by a female soprano with a child-like voice.

Too bad, because otherwise Bernstein’s performance has

much to recommend it. Reri Grist was so much better in the earlier

performance, but Bernstein’s interpretation showed greater

depth in the later one.

The bottom line is that this new version of Mahler’s Fourth

is now the one to beat. I am looking forward to hearing the

recording in surround sound. In the meantime, look no further

for your Mahler 4.

Leslie Wright

|

|