|

|

|

alternatively

CD: AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Download: Classicsonline

|

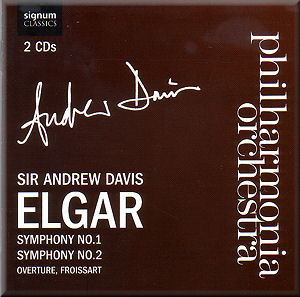

Edward ELGAR (1857-1934)

CD 1

Overture, Froissart, Op. 19 (1890) [15:01]

Symphony No. 1 in A flat major, Op. 55 (1908) [52:51]

CD 2

Symphony No. 2 in E flat major, Op. 63 (1911) [57:23]

Philharmonia Orchestra/Andrew Davis

Philharmonia Orchestra/Andrew Davis

rec. Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, 12 April 2007 (Symphony No. 1,

Froissart) and 20 May 2007 (Symphony No. 2)

SIGNUM CLASSICS SIGCD179 [67:57 + 57:23]

SIGNUM CLASSICS SIGCD179 [67:57 + 57:23]

|

|

|

Andrew Davis previously recorded the two Elgar

symphonies with the BBC Symphony Orchestra in 1991 and 1992. Originally

released on the Teldec label in superb sound, the performances

were widely praised. Those readings are currently available on

Apex for around a fiver each in English money. Now along comes

this two-disc set, recorded live in concert, and released by Signum

as part of their association with the Philharmonia Orchestra.

(I reviewed some months ago a very fine Elgar/Davis disc in the

same series featuring the “Enigma” Variations.) The cost

comes to about half as much again as the Apex discs. So the question

for admirers of Elgar and Andrew Davis is which are the ones to

choose?

The first thing to note is that in terms of overall conception,

as a glance at the timings of each movement suggests, the readings,

separated by sixteen years, are remarkably consistent. Beware,

however, the printed timings of the first disc, which shave nearly

fourteen minutes off the total. The A flat major symphony gets

off to a fine start with a noble slow introduction, resplendent

in sound when the theme is repeated by the full orchestra. The

Allegro is powerful and is characterised, as are all these

performances, by Davis’s familiar mastery of Elgarian style. The

scherzo goes very well and only very few allowances need be made

for the pressures of live performance in those fiendishly scurrying

string parts. The slow movement is delivered with a most moving

restraint, and the finale is brilliantly dispatched, its closing

pages – which rarely fail – extremely exciting. So far so good,

but I was left with a nagging feeling that this performance was

less involving than it should have been. I think Davis might have

pushed harder at the main climax of the first movement and there

are several points in the performance where he seems unwilling

to give the orchestra their head. The woodwind phrasing in the

famous passage in the scherzo – “Play it like something you hear

down by the river”, said Elgar – seems self-conscious and the

conductor’s decision to relax the tempo here leads to a bit of

slightly mannered braking when the theme returns a second time.

These performers don’t quite convince us that the musical material

of much of the finale – lots of sequences – is up to much, and

this at a very fast tempo indeed. And then there is the problem

of the sound, very analytical and close, making it difficult for

the performers to cast the requisite spell in the magical passage

with solo violin in the first movement, and particularly in the

slow movement, which begins several notches above pianissimo

and seems too loud almost throughout. None of these doubts arise

from Davis’s earlier recording where, curiously, given its studio

provenance, the music making seems hotter and more spontaneous.

Sadly, these feelings are confirmed by the performance of the

later work. This has one of the most terrific openings in all

music, and let me say that no listener would think otherwise when

listening to this performance. But with Davis in 1992, at a near-identical

tempo, the playing is even tauter, the brass crescendos more dramatic,

the sensational horn arpeggios in the seventh and eighth bars

more clearly articulated and impetuous. In short, everything that

launches this remarkable symphony on an unsuspecting public is

more vivid and exciting. At other points in this first movement,

where one hopes for mystery one finds calm, and where excitement

should begin to mount – the lead up to the end of the movement,

for example – the music can seem placid. A refusal to linger in

the sublime slow movement might be seen as a virtue, especially

when placed beside some of the more over-affectionate readings

available, but there is more drama in the music than is to be

found here. These two movements are surely amongst the finest

music Elgar ever composed, which cannot really be said for the

two remaining ones. There’s a fair amount of padding in the scherzo,

but the climax of the movement and the lead into it are astonishing.

Elgar himself once addressed an orchestra thus: “… my music represents

a man in high fever … Percussion … I want you gradually to drown

the rest of the orchestra.” What are we to make of this? Did he

mean it literally? In this performance it is the brass and the

percussion which drown the rest of the orchestra, and the result

relentless and unpleasant. The closing pages of the finale are

wonderful, of course, and Elgar’s way with the return of the music

from the opening of the work is masterly and most moving, but

it seems tacked on, so weak and inconsequential is much of the

music which precedes it. Davis manages no better than other conductors

in convincing us otherwise, though, for this listener at least,

one conductor did. Again, the earlier performance is more successful

at all these points.

The first disc is completed by a fine performance of the early

concert overture, Froissart.

These performances were recorded in the Queen Elizabeth Hall,

and though it is many years since I attended a concert there,

I can’t help thinking that it must be far from ideal for a full

symphony orchestra. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why all

concerned seem less engaged with the music than one would expect,

especially in concert. In any event I think it must certainly

explain the sound. The presentation is fine, and includes a highly

readable and informative booklet essay signed M. Ross.

For those seeking recordings of Elgar’s symphonies the choice

is very wide. Barbirolli was a very subjective conductor, and

his readings, which I adore, will not please everybody. Of similar

vintage, several recorded performances by Boult are available,

his mastery of large-scale structures unsurpassed. Solti profited

from studying the composer’s own recorded performances before

setting down his wonderfully exciting readings with the London

Philharmonic Orchestra. Two fascinating and typically idiosyncratic

performances from Sinopoli are well worth investigating, and I

recently made acquaintance with Charles Mackerras’s performances,

a remarkable bargain on Eloquence, and surely amongst the finest

of all. Only one conductor has convinced me in the finale of the

Second Symphony, however, though I am at a lost to explain how

he does it. This is Edward Downes, with the BBC Philharmonic,

on Naxos, and the rest of the performance is very fine indeed

too. And then there are Andrew Davis’s earlier performances, outstanding,

generously coupled, and though I say this with some regret, wanting

to encourage the enterprise of this Signum series, preferable

in most respects to these new performances.

William Hedley

|

|