|

|

|

alternatively

CD: AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Download: Classicsonline

|

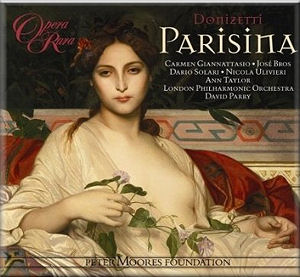

Gaetano DONIZETTI (1797-1848)

Parisina - Tragic melodrama in three acts (1833)

Azzo, Duke of Ferrara - Dario Solari (baritone); Parisina, his wife

- Carmen Giannattasio (soprano); Ugo, who is discovered to be her

stepson - José Bros (tenor); Ernesto, Azzo’s minister

- Nicola Ulivieri (bass); Imelda, Parisina’s lady in waiting

- Ann Taylor (mezzo)

Azzo, Duke of Ferrara - Dario Solari (baritone); Parisina, his wife

- Carmen Giannattasio (soprano); Ugo, who is discovered to be her

stepson - José Bros (tenor); Ernesto, Azzo’s minister

- Nicola Ulivieri (bass); Imelda, Parisina’s lady in waiting

- Ann Taylor (mezzo)

Geoffrey Mitchell Choir, London Philharmonic Orchestra/David Parry

rec. Henry Wood Hall, London, December 2008

OPERA RARA ORC40 [3 CDs: 77.27 + 62.04 + 33.47]

OPERA RARA ORC40 [3 CDs: 77.27 + 62.04 + 33.47]

|

|

|

The year 1833 was even more hectic than usual for Donizetti.

2 January saw the premiere of Il furioso in Rome. After

this the composer hurried to Florence with the intention of

starting work on Parisina the first of two operas he

had promised the impresario Lanari. The year would also see

the premieres of his Torquato Tasso in Rome and Lucrezia

Borgia at La Scala. But Donizetti’s best intentions

with regard to starting work on Parisina were thwarted

by his librettist, Felice Romani. He had taken on too much work

and consequently was unable to deliver the promised verses by

the required date. The same was the situation facing the physically

fragile Bellini as he awaited the libretto for Beatrice di

Tenda in Venice. The outcome broke their personal friendship

and professional relationship, the composer referring to the

librettist as The God of Sloth. That was a bit harsh.

Romani’s problem was over-commitment. Like the composers

of the day it was necessary to work at pace and take on any

offered contracts to keep body and soul in reasonably good shape.

Whilst Parisina was premiered in Florence on 17 March

1833, Beatrice was premiered in Venice the previous day!

Donizetti’s Parisina is based on Byron’s

poem of same name, the story having some similarities with Verdi’s

Don Carlos. It concerns the thwarted love of the young

Parisina and the youthful Ugo. Despite that ardent love she

becomes the second wife of Azzo, Duke of Ferrara, as the reward

for the latter’s rescuing her father’s territories

from the Ghibellines. Despite this match the two maintain their

love. Azzo, whose first marriage was deeply unhappy, is suspicious

of Parisina and watches her closely as she glows with pleasure

at Ugo’s success in the tournament celebrating the marriage.

Azzo tells his minister Ernesto, who brought up Ugo, to banish

him from the castle. The order is not fulfilled and Azzo later

finds Ugo in the presence of Parisina.

Ever more suspicious of Parisina, Azzo watches her as she sleeps

and hears her murmuring Ugo’s name. In fury he tells what

he has heard and forces her to confess. She pleads for death,

which he spurns. Meanwhile Ugo returns to the palace in the

hope of seeing Parisina and is rebuked by Ernesto before armed

guards arrest him. Parisina and Ugo are brought before Azzo

in chains. Parisina pleads that they are in love only in thought

not deed. As they are led away Ernesto tells Azzo that if he

has Ugo executed he would be committing the horrendous crime

of killing his own son, revealing he is the child of Azzo’s

repudiated first wife.

In the short final act Parisina learns, from the chorus lament

for the dead, that Ugo has been executed. In a dramatic double

aria and cabaletta she dies in paroxysms of grief.

Parisina was the first opera Donizetti wrote for the

impresario Lanari’s touring company at his Florentine

headquarters. The singers for the primo were to be an

important influence on his writing. The eponymous role was to

involve a soprano reputed to be a tragic singing actress without

an extended top to her vocal range. The tenor scheduled for

Ugo was in some ways the opposite and reputed to be the first

tenor to sing high C from the chest. Rossini likened the sound

to that of the squawk of a capon about to have its throat

cut! In view of the original soprano’s skills I was

somewhat surprised at Opera Rara’s original choice of

Patricia Ciofi in the title role. In the event she withdrew

and was replaced by the warmer vibrant tones of Carmen Giannattasio;

the role seems to me to fit her like a glove. Certainly hers

is the outstanding performance among the quartet of leading

soloists in this issue. She has the capacity to convey pathos,

love, fear and desperation in her vocal expression. These skills

are evident in the first act as Parisina, whilst glad for her

father worries about her own destiny (CD1 tr.11). This can also

be heard in the following duet with Ugo (trs 13-14) and above

all in the short act three tragic conclusion when, after hearing

of Ugo’s fate at the hands of his father, she dies (CD3

trs.3-6). Yes, some consonants could be better, but her performance

in this recording is of good standard and even if not matching

Caballé on the pirate recording, is a significant achievement.

As Ugo, José Bros’s rather white tone does not

bring the part to life in the same manner as his partner. He

has to strain somewhat with the highest notes as the drama unfolds

in his duet with his guardian Ernesto (CD2 tr.11). Nevertheless

his plangent voice is welcome at other points. The role of Azzo,

the baddy of the story, falls to the young Uruguayan baritone

Dario Solari. His recent Germont in La Traviata for Welsh

National Opera did not impress me. He failed to spark any electricity

in Germont’s act two confrontation with Violetta and likewise

in the second scene when he enters Flora’s party and berates

his son for demeaning Violetta by throwing his gambling table

winnings at her. I suggested, in my review,

that this was may be lack of tonal weight and that perhaps,

as yet, Donizetti was more likely to be his metier. His singing

is certainly smooth, well tuned and easy on the ear, but he

fails to lift the dramatic temperature and sound the real villain.

In act two this is exactly what is required as Azzo first listens

to Parisina breathing his name in her sleep and then forces

her to admit her love for Ugo (CD2 trs.4-6). His singing needs

more tonal bite. In the bass role of Ernesto, who has quite

a lot to sing but no aria, Nicola Ulivieri is more successful

in his vocal expression whilst also maintaining tonal beauty.

In what little she gets to sing Ann Taylor as Parisina’s

companion deserves note.

Musically, Parisina has little of the easy-on-the-ear

melodic invention of Lucia di Lamermoor, composed two

years later. It has, however, more dramatic cohesion and thrust

than found in Lucrezia Borgia (see review)

or Rosmondo d’Inghilterra (see review)

that came between those works. It is more akin to Maria Stuarda

(see review)

from that period. More than anything, I am taken with the similarities

between Parisina and Caterina Cornaro, the last

of Donizetti’s works staged in his lifetime. There are

similarities in dramatic emphasis over sung ornamentation, the

involvement, dramatically and musically of the chorus, allied

to the maturity of style in the orchestral writing.

In this performance both are well realised in the contribution

of the Geoffrey Mitchell Choir and owe much to David Parry’s

passionate conducting (see a review

of a concert performance of Parisina by these forces).

With Opera Rara already having recorded Linda di Chamonix

and with two-thirds of Caterina Cornaro being composed

immediately after, it may be no vain hope that Cornaro

is in their minds for a future project. Certainly, devoted Donizettians,

who are increasingly well served by recordings of Italian Festival

performances, such as those mentioned above, as well as Opera

Rara, would welcome a studio recording uninterrupted by applause

and in good sound.

Parisina was a success at its premiere and quickly spread

through Italy and Europe. It was the first Donizetti opera performed

in America. It survived in Italy until the 1890s the title role

attracting the great divas of each generation. It was performed

in London and Paris in 1838 with the great so-called Puritani

quartet of Giulia Grisi in the title role, the tenor

Rubini whose stratospheric range accounts for the infamous high

F in the last act of Bellini's I Puritani, along with

the formidable Tamburini and Lablache. The cast in this issue

might not match that quartet, but no other has done so since.

The whole is, however, a very welcome addition to the Donizetti

discography.

The issue comes in Opera Rara’s incomparable presentation

including a complete libretto and English translation together

with an introductory article, performance history and synopsis

by the eminent Donizetti scholar, Jeremy Commons. It lacks only

artist profiles for perfection.

Robert J Farr

See also Colin

Clarke's review of the live performance

|

|