|

|

|

alternatively

CD: AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

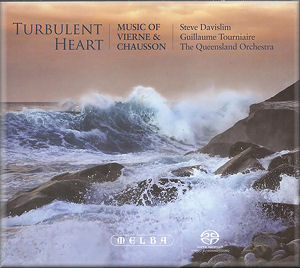

Turbulent Heart

Louis VIERNE (1870-1937)

Les Djinns, Op. 35 (1914) [10:43]

Eros, Op.37 (1916) [12:22]

Ballade du désepéré, Op.61 (1929) [16:49]

Psyché, Op. 33 (1914) [8:38]

Ernest CHAUSSON (1855-1899)

Poème de l’amour et de la mer, Op. 19 (1893) [27:37] (La

fleur des eaux [11:15]; Interlude [2:33]; La mort

de l’amour [13:49])

Steve Davislim (tenor)

Steve Davislim (tenor)

Queensland Orchestra/Guillaume Tourniaire

rec. Studio 420, Brisbane, Australia, 12-13, 15-16, 18 September

2008

Text included

MELBA RECORDINGS MR301123 [76:32]

MELBA RECORDINGS MR301123 [76:32]

|

|

|

This disc contains a number of examples of a particularly French

form: the vocal symphonic poem. Such works can range from a

straightforward scena to a true symphonic poem with sung "accompaniment”

to an integrated work which elucidates the text both vocally

and instrumentally. The Vierne pieces are among the least known

works in his oeuvre, an output many are only now learning extends

beyond the church organ loft. The Chausson is an old favorite,

although in this recording it has a slight twist. Since the

Vierne works are practically unknown, we will devote

most of our attention to them.

Both Psyché and Les Djinns were written in 1914,

although in reverse order. This year also saw the composition

of his famous Pièces en style libre Op.31. Les Djinns

is more or less an orchestral symphonic poem, with the singer

as narrator. Vierne uses the form of Hugo’s poem to build up

the terror of the deadly spirits flying through the air and

then somewhat lessens the ever-present main theme to prepare

for the soloist’s invocation to the prophet for protection.

This is a wonderfully dramatic moment. However, the music associated

with the Djinns never totally disappears and we are left with

a slight feeling of unease at the end, not of triumph or relief.

In Psyché we again have a poem by Hugo, but this work

is slightly more conventional in form, consisting of a poet

posing various questions to a butterfly. The interest lies in

the way the composer varies the main woodwind theme in numerous

ways to keep the music interesting, given the format of the

poem. In this he excels himself both orchestrally and harmonically,

leading to a final invocation that is quite impressive.

Two years can make quite a difference and the years between

1914 and 1916 produced big changes for Vierne, both personally

and professionally. In the latter year his brother and several

of his students were killed in the War and he began to show

signs of the glaucoma that would eventually render him completely

blind. Nevertheless, his work Eros, to a poem by Anna

de Noailles, is about the sunny Mediterranean, though not only

the pleasant aspects. It ends with what can be seen as a plea

for death as escape from life. Musically, it is a true synthesis

of voice and orchestra as a means of expression. Once again,

it is based on a single, atmospheric theme, here even more masterfully

developed than in the previous works. It proceeds from a rather

eerie beginning to a triumphant finale that can only be described

as amazing. Finally it reminds us that triumph can lead to the

grave.

Vierne’s benefactress and muse in the twenties was a lady named

Madeline Richepin. In 1929 he found out that she was to marry

a famous doctor and this put him in a state of extreme upset.

The composer thereupon wrote the Ballade du désepéré

(Ballad of a despairing man) in response, numbering it “Op.61

(and last)”. Eventually there was an Op.62, the Organ Mass

for the Dead, his last work. The Ballade is much

more severe than its three predecessors and is based on several

themes. It is despairing throughout, but also possessed of great

drama and shows a more supple use of the solo voice. The poem

describes the incessant knocking at the door by Death and the

main character's acceptance, indeed, happiness, once he realizes

that Death has arrived. There is a beautiful cello solo at the

end as the situation is resolved, before a return of the opening

material.

The Chausson Poème de l’amour et de la mer is usually

sung by a soprano, but the original score specifies a tenor

and that is the version here. Unlike the Vierne works, the Chausson

consists of two vocal scenas or poems linked by an orchestral

interlude. But the musical construction turns the parts into

a complete symphonic poem. The first section, La fleur des

eaux (The flower of the waters) is a description of the

beloved in terms of lilacs, elaborating on the first of the

work’s two main themes. The second theme enters, worried and

agitated, describing the parting from the beloved in terms of

the imagery of the sea and waves of agony. The Interlude

continues the second theme, but even more mournfully. The

second movement proper, La mort de l’amour (The Death

of Love) starts with a variant of the second theme and goes

through funereal waves of despair before leading to a section

where the soloist is accompanied by a single cello. Finally

there are reminiscences of the first theme, before the soloist

and cellist state that the time of lilacs is over.

There are many recordings of the Chausson available. A couple

of the classics are those with Dame Janet Baker [see

review] and Jessye Norman. More recently there have been

Linda Finnie and Jean-Francois La Pointe [see

review]. Steve Davislim shows sufficient intensity and poetic

control so as not to suffer by comparison with these others.

In addition, he must handle an extremely wide range of emotions

in the various works on this disk. He does so with distinction,

from the ecstasy of parts of the Chausson to the depths of Vierne’s

Ballade du désepéré. His readings of the poetry are very

clear and he never loses sight of the main musical structure

of each piece. The Queensland Orchestra plays with real devotion;

perhaps as well as I have ever heard them. Part of this is due,

I am sure, to the leadership of Tourniaire, who achieves an

idiomatic French sound throughout and further demonstrates the

ability he has shown in his recording of Saint-Saëns’ Hélène

[see

review]. The SACD is clear, without being overly sharp,

as some such recordings are. One must make especial mention

of the very erudite notes by Jacques Schamkerten and of the

lavishness of the overall presentation.

William Kreindler

see also review by Dominy

Clements

|

|