|

|

|

alternatively

CD: Crotchet AmazonUK AmazonUS

Download: Classicsonline

|

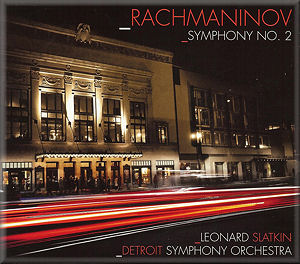

Sergei RACHMANINOV (1873-1943)

Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27 (1908) [54:05]

Vocalise, Op. 34, No. 14 (1915) [6:38]

Detroit Symphony Orchestra/Leonard Slatkin

Detroit Symphony Orchestra/Leonard Slatkin

rec. Orchestra Hall, Detroit, USA, 24–27 September 2009

NAXOS 8.572458 [60:43]

NAXOS 8.572458 [60:43]

|

|

|

A successful performance of almost any major Rachmaninov work

will leave the listener thinking that the music is better than

it really is. In the case of the E minor Symphony, the performers

must somehow disguise the episodic nature of each of the movements,

the work being, in effect, a series of glorious moments connected

by frequently rather contrived transitions. Something has to

be done, too, about those passages where the level of inspiration

falls below the line - the middle section of the finale, for

example. The success of the whole work rests on melody. It is

full of big tunes, ardent and surging, but these are constructed

for the most part using stepwise motion, with rising sequences

employed to increase tension. If we are not to think this artificial,

a no-holds-barred attitude has to be adopted.

Leonard Slatkin’s way with these big tunes, almost always played

by the violins or massed strings, is to keep cool and bring

out the counter-melodies. The trouble is that these counter-melodies,

played by the horns or other members of the wind band, are often

little more than undistinguished figuration designed to enrich

the harmony and texture. The second theme of the first movement

gets this treatment. It is also given very slowly, both in relation

to the main tempo of the movement and to the composer’s metronome

mark. In fact Slatkin, like many conductors, is quite cavalier

about the composer’s markings throughout the performance. How

revealing it would be, just once, to hear a Rachmaninov performance

wherein every crescendo or tempo change began exactly at the

point indicated by the composer! There are a few odd balances

in the development section of this same movement, and that after

a slow introduction which is grim and menacing where dark melancholy

is what we usually expect. Rachmaninov marked the exposition

to be repeated, but Slatkin ignores this; there can be no argument,

in the early twentieth century, that this was merely a convention.

Perhaps he was worried about the audience’s attention span,

because – and there is no indication anywhere of this – this

is a live recording. The audience is in fact commendably quiet

until the inevitable final cheers.

The second movement is taken very fast, to the point of sounding

rushed and breathless, especially the middle section with its

short brass band interlude. The principal clarinettist plays

the long solo in the slow movement beautifully, but many will

wish the instrument had been more prominent in the overall texture.

Subsidiary parts are again brought out when this theme returns

towards the end of the movement. The finale is brilliantly played,

but there is little feeling that the final pages represent the

culmination of any kind of symphonic journey, and not much excitement

is generated.

Listening to this performance, one doesn’t get the feeling that

the conductor is totally convinced by the work, still less that

he loves it. Gennadi Rozhdestvensky though, conducting the London

Symphony Orchestra in 1988 (reissued

on the super-budget label Regis) plays the work for all

it is worth, perhaps for more than it is worth. He leaves one

convinced that it is a masterpiece. He caresses and cajoles,

and his control of phrasing, pulse and texture is immensely

subtle. He consistently finds the right tempo – taking significantly

more time in all four movements than Slatkin – and the music

always has time to breathe, even in the faster passages.

Another fine performance is, perhaps surprisingly, that by James

Loughran and the Hallé Orchestra from 1973, available in EMI’s

Classics for Pleasure series (5755652). The Free Trade Hall

recording is inferior to that for either Rozhdestvensky or Slatkin,

with considerably less orchestral detail, and you don’t get

the exposition repeat. But the conductor’s view of the piece

is totally convincing and the orchestra play like heroes. Much

as I admire both these performances, the finest on my shelves,

and perhaps the finest I have ever heard, is neither of these,

but one recorded in 1994 and issued free with the BBC Music

Magazine (BBC MM127, 1994, Vol. III No. 3). The BBC Philharmonic

is conducted by the late Edward Downes. It is a reading of extraordinary

conviction and stature, and should certainly be made more widely

available.

The orchestral playing on Slatkin’s Detroit performance is brilliant

throughout, but there is a sheen to the sound which is far removed

from anything Russian. The reading is cool and efficient, missing

out on much of the tenderness, melancholy and excitement which

other interpreters have found in the work. Many finer performances

are available – one shouldn’t forget Previn’s

reading on EMI – but for my money few are as fine as Rozhdestvensky’s.

You won’t get any extra music – though Slatkin’s performance

of the lovely Vocalise is hardly going to make any real

difference – but you will want to stand and cheer at the end,

probably even more loudly than the Detroit audience does.

William Hedley

|

|