|

|

|

alternatively

CD: Crotchet

|

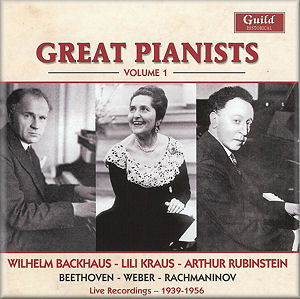

Great Pianists – Volume 1

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Piano Concerto No. 4 in G, Op. 58 (1805/6) [32:52] ¹

Carl Maria von WEBER (1786-1826)

Konzertstück (1821) [16:14] ²

Sergei RACHMANINOV (1873 - 1943)

Variations on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43 (1934) [21:53] ³

Wilhelm Backhaus (piano); New York Philharmonic Orchestra/Guido

Cantelli, rec. live 1956 ¹ Lili Kraus (piano); Concertgebouw Orchestra/Pierre

Monteux, rec. live 1939 ²

Wilhelm Backhaus (piano); New York Philharmonic Orchestra/Guido

Cantelli, rec. live 1956 ¹ Lili Kraus (piano); Concertgebouw Orchestra/Pierre

Monteux, rec. live 1939 ²

Artur Rubinstein (piano); New York Philharmonic Orchestra/Victor

De Sabata, rec. live c.1953 ³

GUILD GHCD 2349 [71:02]

GUILD GHCD 2349 [71:02]

|

|

|

There’s no especial logic at work, no alchemical organising principle that conjoins these three performances, other than the fact that the series rubric says it all. As an umbrella title I think ‘Great Pianists’ says it nicely, though I can imagine that pianophiles, second only to Vocal Art Specialists, surely, in their feline acerbity will have something to say about it. Let’s not worry too much about them. Let’s worry about the music.

We don’t lack for examples of Backhaus’s Beethoven on disc but we should be cavalier in the extreme were we to turn away from the meeting between this discographic pioneer and the incendiary Cantelli. The meeting between the two seems to have been one of agreeing minds if this performance is representative. That’s to say it’s not at all the kind of disastrous meeting that Cantelli had with Heifetz – their live Mendelssohn concerto is something of a fiasco – and the one he apparently had with Solomon. The ensemble is watertight, the direction sympathetic without being over-courtly, and the recorded balance very reasonable indeed. Backhaus is on excellent form. He is technically and interpretatively from the top drawer here – leonine, masculine, purposeful, expressive, powerfully persuasive, tonally subtle, and with a magnificent first movement cadenza. This is the kind of playing that has one listening anew. His control in the slow movement is eloquence itself, his projection has oases of interior introspection; the whole is the product of long experience and unimpeachable authority. Once into the finale the thematic play of left and right hands proves arresting - he always has interesting phrasal things to say – and the vitality and drama prove irresistible. This is a marvellous performance from a pianist then, and now, too often taken for granted.

The same can never be said of Rubinstein, whose stewardship of his own repertoire was of so long a duration, and whose esteem only grew over the decades. He essays the Rachmaninov Paganini variations, a work he recorded commercially. He again proves himself a lissom, no-holds-barred interpreter of this particular muse. He finds a somewhat unlikely ally in De Sabata. Rubinstein certainly breathes Grendel-like fire into the variations but it is all a bit hectic, as it was often to be in his forays into Rachmaninov’s music. The occasionally daemonic moments are exciting but a little too calculated to appeal to the bejewelled stalls and gallery. There is certainly magisterial power here, for sure, but not quite the concomitant repose and grace under fire.

The pre-War live performance of Weber’s Konzertstück is in the safest of hands in Lili Kraus, and she is partnered by the impregnable Monteux at the head of the Concertgebouw forces. The sound is good for 1939 and the frequency response impressive. Kraus plays with all her expected imperturbable dynamism.

So, whatever criterion one adopts for this triptych of live performances one thing is for sure; boredom is not on the agenda. There is one indisputably great performance – that of Backhaus. There’s an exciting pre-War survival of a glittery showpiece, and a contentious example of Rubinstein operating at white heat.

Jonathan Woolf

|

|