|

|

|

alternatively

CD: AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Download: Classicsonline

|

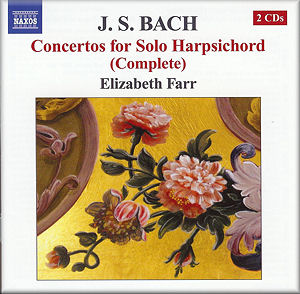

Johann Sebastian BACH (1685–1750)

Concertos for Solo Harpsichord

CD 1

Concerto in D major, BWV 972 (after Antonio Vivaldi, RV230) [8:10]

Concerto in G major, BWV 973 (after Antonio Vivaldi, RV299) [7:58]

Concerto in g minor, BWV 975 (after Antonio Vivaldi, RV316) [8:56]

Concerto in C major, BWV 976 (after Antonio Vivaldi, RV265) [10:53]

Concerto in F major, BWV 978 (after Antonio Vivaldi, RV310) [7:31]

Concerto in G major, BWV 980 (after Antonio Vivaldi, RV381) [9:53]

Concerto in C major, BWV 977 (after an unknown composer) [7:19]

Concerto in g minor, BWV 983 (after an unknown composer) [8:58]

Concerto in G major, BWV 986 (after an unknown composer) [6:20]

CD 2

Concerto in b minor, BWV 979 (after Giuseppe Torelli) [12:13]

Concerto in d minor, BWV 974 (after Alessandro Marcello) [8:44]

Concerto in c minor, BWV 981 (after Benedetto Marcello, Op. 1, No.

2) [8:55]

Concerto in B flat major, BWV 982 (after Johann Ernst, Op. 1, No.

1) [8:42]

Concerto in C major, BWV 984 (after Johann Ernst) [8:27]

Concerto in d minor, BWV 987 (after Johann Ernst, Op. 1, No. 4)

[7:05]

Concerto in g minor, BWV 985 (after G. Philipp Telemann, TWV51:

g21) [7:28]

Prelude and Fugue in a minor, BWV 894 [12:08]

Elizabeth Farr (harpsichord)

Elizabeth Farr (harpsichord)

rec. Ploger Hall, Manchester, Michigan, USA, August 2008. DDD.

NAXOS 8.572006-07 [76:26 + 74:09]

NAXOS 8.572006-07 [76:26 + 74:09]

|

|

|

The works recorded here must not be confused with the more

popular and more frequently recorded pieces which are also

often known

as Bach’s solo harpsichord concertos, those for keyboard and

orchestra, BWV1052-9.

During his Weimar period, around 1713-14, Bach made 21 or 22

keyboard transcriptions of concertos by Italian and German composers.

The five or six for two keyboards and pedals (for the organ

or pedal harpsichord), BWV592-6 and the possibly spurious 597,

are comparatively well known and have been recorded a number

of times, including by Wolfgang Rübsam, the producer of the

current recording, for Naxos (8.550936).

What Bach did was, in a sense counter-intuitive; when Locatelli

made orchestral concertos out of Corelli’s sonatas, he added

extra colouring to the originals. Bach stripped his originals

of some of that colour, more so in the harpsichord arrangements

than in the organ concertos, though the versatility of Elizabeth

Farr’s instrument and of her playing restores a degree of the

colour.

The reasons why he made these transcriptions remain a matter

for speculation. Obviously, they were useful exercises for the

young composer, and Farr considers the implications of this

in her notes, but she also surmises that they may have had an

even more practical purpose in satisfying the requirements of

Prince Johann Ernst, himself an accomplished composer whose

music features among both the organ and harpsichord concertos,

and who was studying with the Weimar organist. This is not a

new theory – it is offered by Malcolm Boyd in his 1983 Master

Musicians book on Bach as the most likely reason for these compositions

– but it makes sense and it places the music on much the same

footing as the Well-tempered Clavier. If there is room

for recordings of that, why not have one of these concertos,

too?

Whether the sixteen harpsichord concertos are as worthy of a

modern recording as those intended for the more versatile organ,

when we have at our disposal recordings of the orchestral originals

in most cases, is a moot question. Given the limitations of

the harpsichord, would this 2-CD set turn out to be a 150-minute

yawn? In fact, Elizabeth Farr has to resort to a modicum of

trickery to prevent the boredom from setting in; though the

instrument which she employs is a modern reproduction by Keith

Hill of a Rütgers instrument, it possesses a 16’ stop. This

seems an odd decision when she made her earlier recording of

music by Peter Philips on an authentic instrument from only

slightly later than the music, an instrument restored by the

selfsame Keith Hill. (8.557864 – see review).

In his note in the booklet, Keith Hill admits that 18th-century

harpsichords with a 16’ set of strings were rare and the instrument

which he has created comes perilously close to recreating the

sound of the metal-framed monsters which we thought we had seen

the last of, as played by the likes of Rafael Puyana, pictured

on one Mercury LP sleeve seated at an instrument larger than

a modern concert grand. (See my review

of Peter Watchorn, Isolde Ahlgrimm and the Early Music Revival,

Aldershot, England: Ashgate Publishing, 2007).

Surprisingly, when I sold off that Puyana LP, I was offered

what I thought a ridiculously large sum for it, so there is

obviously still a demand for large-toned harpsichord recordings.

The new CDs should satisfy that demand – and I must admit that

Elizabeth Farr’s performances did mostly serve to still the

voice of authenticity within me.

Occasionally she goes at the music hammer-and-tongs, as in the

third movement of the b-minor concerto after Torelli, BWV979

(CD2, tr.3) and the adagio of the c-minor concerto after Marcello,

BWV981 (CD2, tr.12), but she also produces some extremely delicate

playing, as in the Adagio of the d-minor concerto after

Marcello, BWV974 (CD2, tr.8).

By comparison with Robert Woolley’s recording of the six concertos

after Vivaldi (details below), she adopts slower tempi in the

outer movements and faster tempi in the slow movements. Comparing

her version of BWV972 (CD1, trs.1-3) with Woolley’s, I have

a clear preference for the latter, made on a brighter-toned

harpsichord, a 1982 copy of a Franco-Flemish instrument.

Woolley takes a whole minute longer for the central Larghetto

– 3:48 against 2:47 – thereby giving real weight to the music

and providing a real contrast with his nimble-fingered tempi

for the opening Allegro – 2:20 against Farr’s 2:33 –

and Allegro finale – 2:19 against 2:50, all this achieved

without sounding at all hectic in the outer movements or sluggish

in the central movement. By comparison, Farr sounds too emphatic

at the opening of the first movement and elsewhere. In the Larghetto

her more versatile instrument allows her greater tone colour,

but I find her just too fast here to do justice to the music.

The second CD is completed with a performance of the Prelude

and Fugue in a minor, BWV894. Here my benchmark is another Hyperion

recording, from Angela Hewitt, who includes the work to conclude

her 2-CD set of the French Suites (CDA67121/2). As with

the Woolley recording, direct comparison with Hewitt – one of

the few pianists whose Bach I really like – is much faster in

both sections than Farr. Yet Hewitt’s Prelude sounds deliberate

rather than rushed and her fingers negotiate the fugue without

a hint of scrambling. Listen to the short samples from each,

on the Hyperion

website and Naxos’s sister website, classicsonline,

and you’ll see why I like Farr’s performance but prefer Hewitt.

Are Farr’s performances overall good enough for me to recommend

investing in the 2-CD set? In fact, she has already successfully

sold an even larger collection of keyboard music to my colleague

Kirk McElhearn, who thought that you really couldn’t go wrong

with her 3-CD set of Byrd’s keyboard music (8.570139-41 – see

review).

Glyn Pursglove also found her 2-CD recording of the music of

Elizabeth Jacquet de la Guerre convincing (8.557654/5 – see

review).

She employed four different instruments for the Byrd recording,

a lute-harpsichord, a single-manual and two two-manual harpsichords.

There might have been a case for such variety again here, though

the one instrument achieves a large degree of variety for the

very reason that caused my reservation, the use of 16’ tone

– to paraphrase TS Eliot, she achieves the right outcome for

the wrong reason.

I may have been a little too sniffy about the 16’ tone, but

I was less enthusiastic than KM or GP were about those earlier

recordings. I was, however, pleased enough with the outcome

to want to investigate her 2-CD set of Bach’s music for that

curious instrument the Lautenwerck or lute-harpsichord. As I

was writing this review my wife came into my study more often

than usual to share what she thought a wonderful sound, so I’m

out-voted.

Elizabeth Farr has the field more or less to herself in these

solo concertos. Her performances are never less than interesting

and the set is on offer at an attractive price, so it’s certainly

worth buying. The only rival of which I am aware is the recording,

referred to above, which Robert Woolley made of the six concertos

after Vivaldi for Hyperion in 1988, available only from the

Special Archive Service or as a download from Hyperion

(CDA66224, mp3 or lossless). The download is offered, in either

format, for a mere £5.99 – money well spent, perhaps in preference

to this Naxos set.

The Naxos recording is good and the documentation, by Elizabeth

Farr herself, detailed, informative and readable. There is also

a reasoned argument by Keith Hill for the specification of the

instrument which he built for her.

A recent batch of review CDs has brought Elizabeth Farr on another

Naxos 2-CD set, again using the 16’-capable Keith Hill instrument,

this time of the harpsichord music of Claude-Bénigne Balbastre

(8.572034/5). To the best of my knowledge, French instruments

never sported 16’ tone, so the result should be even more interesting

than the Bach CDs. Watch this space.

Brian Wilson

|

|