|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

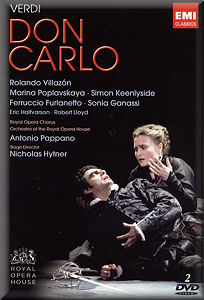

Giuseppe VERDI (1813-1901)

Don Carlo Opera in Five Acts (sung in Italian) (1886, Modena version)

Philip, King of Spain - Ferruccio Furlanetto (bass); Don Carlo, Infante of Spain - Rolando Villazón (tenor); Rodrigo, Marquis of Posa - Simon Keenlyside (baritone); The Grand Inquisitor - Eric Halfvarson (bass); Elisabeth de Valois, Philip's Queen - Marina Poplavskaya (soprano); Princess Eboli, Elisabeth's lady-in-waiting - Sonia Ganassi (mezzo); Tebaldo, Elisabeth's page - Pumeza Matshikiza (soprano); The Count of Lerma - Nikola Matišic (tenor); An Old Monk - Robert Lloyd (bass); A Voice from Heaven - Anita Watson (soprano) Philip, King of Spain - Ferruccio Furlanetto (bass); Don Carlo, Infante of Spain - Rolando Villazón (tenor); Rodrigo, Marquis of Posa - Simon Keenlyside (baritone); The Grand Inquisitor - Eric Halfvarson (bass); Elisabeth de Valois, Philip's Queen - Marina Poplavskaya (soprano); Princess Eboli, Elisabeth's lady-in-waiting - Sonia Ganassi (mezzo); Tebaldo, Elisabeth's page - Pumeza Matshikiza (soprano); The Count of Lerma - Nikola Matišic (tenor); An Old Monk - Robert Lloyd (bass); A Voice from Heaven - Anita Watson (soprano)

Orchestra and Chorus of The Royal Opera House/Antonio Pappano

rec. live, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London 14, 17 June, 3 July 2008

Directed by Nicholas Hytner. Costume and Set Design by Bob Crowley

A co-production with the Metropolitan Opera, New York and Norwegian National Opera

Video presentation 4:3 PAL

Sound in Stereo

Region free; NTSC Colour; Filmed in HD 50i 16:9 widescreen; For playback on all NTSC and PAL systems worldwide

Sound formats, LPCM Stereo. DTS 5.1 surround

Booklet essay and synopsis in English, French, German

Subtitles in Italian (sung language), English, German, French and Spanish

EMI CLASSICS 6316099 [2 DVDs: 126:00 + 85:00]

EMI CLASSICS 6316099 [2 DVDs: 126:00 + 85:00]

|

|

|

After the staging in 1859 of Un Ballo in Maschera, his twenty-third opera, Verdi often talked about hanging up his compositional pen. However, if the money was right and the situation appealed, he was open to offers.

An impatient man he did not take kindly to the endemic bureaucracy at the Paris Opéra and, after the production of Les Vêpres Siciliennes, at the theatre in 1855, he swore never to compose for it again. But he and his wife liked Paris where they had lived for a time prior to their marriage, well away from the scrutiny of Italy. The two returned there when Verdi agreed to re-write his Macbeth of 1847, to a French libretto, for Paris’s Théâtre Lyrique and when only asked to insert a ballet. Following the death of Meyerbeer in 1864, and with an International Exhibition scheduled for 1867, the Paris Opéra were desperate for a five act extravaganza complete with ballet, to mark the occasion. After promises about rehearsal and singers from the Opéra management Verdi relented, and after much consideration settled on Schiller’s Don Carlos, Infant von Spanien of 1787 as the subject of his Grand Opera.

Don Carlos was to be Verdi’s longest opera. It became evident during rehearsals that it would be too long even for Paris with a scheduled finishing time that would not allow the audience to catch their last trains home. Much music was ditched and not re-discovered until the 1970s since when some has been re-inserted into several productions recorded on CD and DVD. The premiere of the original French language five-act form of Don Carlos at the Paris Opéra on 11 March 1867 was only modestly received. This was quickly translated into Italian and given as Don Carlo in Bologna in September 1867, and then in Rome and the remainder of the Italian peninsula where the audience response was little better than in Paris. Both the Italian public and the theatre managements found the opera too long and were slow to take it to their hearts; it was not long before the act three ballet, and then act one, the Fontainebleau act, were dropped. After another failure in Naples, Verdi made his own first alterations to the score for a revival under his own supervision. These changes involved the Philip-Posa duet in act 2, which is the only part of any of his revisions of the opera that the composer did not set to a French text; it is significantly more dramatic than the original Paris version (DVD 1 CHs 22-24). Still the fortunes of the opera disappointed the composer and he began seriously to consider shortening the work. With other demands on his time Verdi did not begin serious work on this until 1882, concluding his revision as a four act opera the following year with the premiere at La Scala having to wait until 1884. This new shorter four-act revision involved much re-wording to explain the sequence of events and to maintain narrative coherence. Verdi’s own reworking also involved the removal of all of act one, except for Don Carlo’s aria that was inserted into the new opening scene. He also removed the ballet, the Inquisitors’ chorus in act five and various other detailed changes. The premiere of this new four-act Don Carlo has become known as the 1884 version. It was a great success at La Scala and featured the tenor Tamagno, who created the title role in Otello three years later, as Don Carlo.

After the 1884 performances of the four-act Don Carlo, a friend asked Verdi whether he regretted the loss of so much music from the original score. He had already told his friend that the new version had more concision, more muscle and added that, those who complained about the loss of so much beautiful music from the first act quite possibly did not notice its existence before. But others were less sure and performances were given in Modena in 1886, claimed to be with Verdi’s permission, which reintroduced the original act one into the 1884 revision. It was in this five-act form, albeit with various minor cuts, that Don Carlo was launched to the post Second World War operatic public in a production by Visconti and conducted by Giulini at London’s Covent Garden on 12 May 1958 (see review). This present production can be seen as standing in direct lineage with those seminal performances, but with the minor cuts opened to give a true representation of the final version that Verdi himself knew and which has come to be known as the 1886 Modena Version.

This staging by National Theatre director Nicholas Hytner, in costumes and sets by Bob Crowly, marked the tenor Rolando Villazón’s return to the house in the title role. This was after he had been forced to to take a rest from singing with evident threats to his vocal well-being. Certainly, his vocal timbre is distinctly more baritonal than a few years earlier when he concentrated more on the bel canto repertoire such as L’Elisir d’Amore (see review) and less demanding Verdi (see review). Just occasionally there are signs of vocal effort, particularly when he addresses himself totally to the evolving drama, which he frequently does with full body committed acting. He allies these occasions to many varieties of facial expression as he conveys the agonies of the role and Don Carlo’s complex psyche to the full. This is evident from act one when Don Carlo goes from love to despair as he is left alone, bereft, on the stage and his bride to be goes off to marry his father in the interests of political stability between France and Spain (DVD 1 CHs 2-8). Likewise his portrayal of the broken spirit of Don Carlo as his friend Rodrigo, to the poignant reprise of the melody of their friendship duet, demands his sword after Carlo had threatened the King and when no other noble would do so (Disc 1 CH.36). It is pleasing to hear Villazón with something left of his mezza voce and a willingness to use it. His ardent singing in the act five meeting between Don Carlo and Elisabeth (DVD 2 CHs.16-18), and impassioned singing in the earlier prison scene with Rodrigo (DVD 2 CHs. 9-13) may have their flaws, but these are more than compensated for by the virtues of tonal expression and elegance of phrase as well as excellent characterisation. More vocal problems for the singer since this performance have, regrettably, left grave doubts as to his future on the operatic stage.

Marina Poplavskaya, Don Carlo’s intended bride, who becomes his Queen and, by title, his mother, is a revelation to me. Her angular features are somewhat too pronounced in the excessive camera close-ups during the act five aria Tu che le vanità (DVD 2 CH. 15). However, she certainly matches Mirella Freni in the DVD recording from New York in her beauty of vocal expression, characterisation and smooth legato, all allied to committed acting. She is as good as the several distinguished sopranos on the audio recordings mentioned. I am more equivocal about Sonia Ganassi as Princess Eboli; the woman who Don Carlo could marry and yet spurns as he yearns for his lost love. Ganassi navigates the Moorish Song Nei giardin del bello with rather too much care (DVD 1 CH 14) whilst her plea to Elisabeth in act 4, as she confesses her adultery with the King in Pietà! Pietà! Perdon and vocal bite in O don fatale, o don crudel are altogether better (DVD 2 CHs 7-8). In between her acting persona did not grip me.

The acted portrayals of the lower-voiced males are wholly commendable. Most notable, as singer and actor, is Simon Keenlyside as Rodrigo. He sings Valentin in the Faust from Covent Garden issued parallel to this (EMI DVD 50999 6 31611 9, to be reviewed). In the intervening three years between the performances his voice has grown and darkened. If Keenlyside lacks a little in ideal Italianate squilla his musicality, acted commitment and vocal expression more than compensate. He is a superb foil to the King in the dramatic act 2 duet that Verdi re-wrote (DVD 1 CHs 22-24) with Philip’s chilling concluding warning Ti guarda dal Grande Inquisitor and Rodrigo’s single word response, Sire, as he is left to ponder the actions of a feared despotic King who treats him as an equal, not a subject, and trusts him with access to his wife (DVD 1 CHs 22-24). Ferruccio Furlanetto recorded the role of Philip for Karajan at Salzburg in 1986 in a performance of the 1884 four-act version (see review). It was relatively early in his career and his interpretation lacked some depth. In recent years King Philip has become something of a signature role for him. He certainly brings plenty of expression and basso cantante solidity to his act four soliloquy Ella giammai m’amò! if not ideal steadiness (DVD 2 CHs 1-2). His singing does not erase memories of Christoff in either the first studio recording of the four-act version (see review) or in the seminal performance at Covent Garden in May 1958 (see review). Likewise he is no match for Solti’s Ghiaurov on Decca’s 1965 audio recording (Decca 421 114), and rather late in his career on DVD at the Metropolitan Opera, New York. This resplendently dressed production, with Domingo in the eponymous role, includes some of the re-discovered music (DG 00440 073 4085). On this occasion the dramatic meeting between two basses with the entry of Eric Halfvarson’s Grand Inquisitor brings out the best in the two singers, who manage to make the confrontation chillingly telling without it descending into a vocal slanging match (DVD 2 CH 3). Robert Lloyd, himself having sung Philip in one of the many revivals of the Visconti production, is a sonorous monk; Verdi never quite knew if he was the ghost of Charles the IV, father of Philip, who appears at the gate of the Monastery of St Juste in act two (CHs 9-10) to save Carlos from the Inquisition at the conclusion of the opera (DVD 2 CH.18).

Musically the whole is brought to fruition with the pacing of Antonio Pappano and the contribution of the Covent Garden forces. Nicholas Hytner’s production has inspired moments of detail, such as in act two when the king leaves, telling Rodrigo to beware the Grand Inquisitor and refuses to let the kneeling soldier kiss his hand as would be protocol, rather having him stand as an equal. The flip side is when Philip contemplates picking up a knife to stab the Grand Inquisitor as their meeting gets steamy (DVD 2 CH.3). The costumes are in period whilst the sets are largely representational. There is much use of curtains and sidewalls with square window type spaces as if to represent the inward-looking nature of this closed court, predominantly black costumed. The gaol episode and death of Rodrigo (CHs 9-13) lack atmosphere whilst the auto da fé scene is a mishmash of lost opportunities, lacking focus, dramatic cohesion and bite, all of which it could so easily have had. The scene is not helped by the insertion of rabble-rousing spoken words by a priest, words that Verdi certainly never saw (DVD 1 CH.32). The sacrificial Brabantais look ridiculous in their costume and hats (DVD 1 CHs 31-36). One could say that Visconti did it all so much better … but time moves on!

The picture in HD is superb whilst the camera-work is often too fussy. The sound is excellent and whilst the essay in the booklet is informative the lack of Chapter listings and timings is regrettable.

Robert J. Farr

|

|