|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

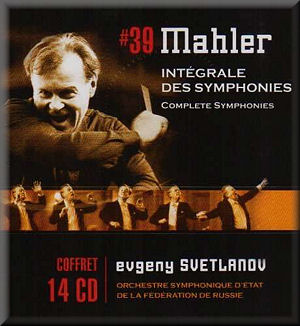

Gustav MAHLER

(1860-1911)

The Symphonies

CD 1: Symphony No. 1 (1884-96) [56:55]

CD 2-3: Symphony No. 2 “Resurrection” (1888-94) [87:49]

CD 4-5: Symphony No. 3 (1895-6) [96:45]

CD 6: Symphony No. 4 (1899-1901) [60:33]

CD 7: Symphony No. 5 (1901-2) [72:57]

CD 8-9: Symphony No. 6 (1903-05) [79:53]

CD 10-11 Symphony No. 7 (1908) [85:19]; Symphony No.10 Adagio (1910)

[31:46]

CD 12-13 Symphony No. 8 (1909) [83:33]

CD 14 Symphony No. 9 (1909) I-II [75:48]

Natalia Gerassimova (soprano) (Symphonies 2, 3, 4, 8), Galina Borissova (mezzo)

(Symphony 8), Olga Alexandrova (mezzo) (Symphony 2, 8), Alexei Martynov (tenor)

(Symphony 8), Dimitri Trapeznikov (baritone) (Symphony 8), Anatoly

Safiulin (bass) (Symphony 8), Galina Boiko (soprano) (Symphony 8),

Ludmila Golub (Organ) (Symphony 8)

Natalia Gerassimova (soprano) (Symphonies 2, 3, 4, 8), Galina Borissova (mezzo)

(Symphony 8), Olga Alexandrova (mezzo) (Symphony 2, 8), Alexei Martynov (tenor)

(Symphony 8), Dimitri Trapeznikov (baritone) (Symphony 8), Anatoly

Safiulin (bass) (Symphony 8), Galina Boiko (soprano) (Symphony 8),

Ludmila Golub (Organ) (Symphony 8)

Russian TV Academic Choir (Symphony 2); Ostankino Television Russian

Academic Choir, Moscow Boys’ Cappella (Symphony 3); Moscow Choral

Academy Children’s Choir, Moscow Choral Academy Mixed Choir (Symphony

8).

Russian State Symphony Orchestra/Evgeny Svetlanov

rec. 1992-1996, Large Hall, Moscow Conservatory

full listing at end of review

WARNER CLASSICS AND JAZZ 2564 68886-2 [14 CDs:

733:07]

WARNER CLASSICS AND JAZZ 2564 68886-2 [14 CDs:

733:07]

|

|

|

Re-released in a single box as part of the Warner ‘Official

Collection’ for the recorded output of Evgeny Svetlanov, most

of these Mahler symphonies first appeared on Chant du Monde.

As you might expect, these Russian recordings have a different

feel to the numerous alternatives on the market, and a good

deal of water has passed under the bridge since the 1990s. Even

just the past ten years has seen a marked improvement in orchestras

beyond the ‘big name’ organisations who have already been under

the microscope of the microphone for the last fifty years or

so. While there are powerful moments and a great sense of promise

with many of Svetlanov’s recordings there are always aspects

which remind one that this is not a crack team quite as steeped

in the Viennese Mahler tradition as one might hope. Interest

is generated in an orchestra and an approach which has its own

individual character, something which has to a great extent

already been leached out of most if not all national orchestras

today. As a representative of resistance against orchestral

androgyny, Svetlanov’s Mahler is a potent statement indeed,

and his fans will be glad to see this cycle made available in

a single set. There are unfortunately too many factors militating

against however, to put this set anywhere near recommendation

as a library first choice.

The Symphony No.1 is pretty decent, though the initial high

harmonic from the strings does have a few squeaks revealing

players a little less comfortable than others with their flageolet.

There is a nice sense of atmosphere in this opening however,

and I like the vulnerable feel to the horns as they enter at

about 2 minutes in and the hunting call later on at 11:05 –

not quite deciding on whether to play with or without vibrato.

The pastoral feel of the rest of this first movement is cautious

rather than really jaunty, with a few little blemishes like

the flute ‘kick’ at 6:53. The second movement is more Kräftig

than bewegt, being perhaps a little on the leaden side, but

still a fair performance. The brass balance is a recurring issue

in these recordings, with the trumpets cutting through with

unnecessary fierceness. Woodwind intonation is another bugbear

at moments throughout this cycle, and the tricky opening of

the funereal third movement has a rather droopy bassoon solo,

making the course steered by timps and bass all the more fragile.

There is a good deal of ‘soul’ further on in this movement however.

Mahler might not have had Cossacks as a mental picture for this

piece, but they certainly sprang into my mind at times. The

trumpet entry at 9.30 has to be heard to be believed, with such

marvellously soggy vibrato to make one suspect the trumpets

are taking the mickey. All the score says at this point is etwas

hervortretend – or ‘with a little more emphasis’, not go completely

mad with some kind of bizarre satire. The final movement suits

everyone down to the ground here, with plenty of opportunity

for rip-roaring bombast and plenty of soupy sentiment.

Mahler’s Symphony No.2 is a piece for which I have something

of a soft spot. I can go along with Svetlanov’s tempi for the

first three movements, and there are numerous powerful and beautiful

moments to enjoy, the perspective of the orchestra now more

distant and the effects of the acoustic in the Moscow Conservatory

Large Hall more pronounced. Where this symphony starts to wobble

a little is at the very point it should start to lift one to

the heavens. Olga Alexandrovna’s initial entry in the ‘Urlicht’

movement is a bit flat, and there are quite a few notes where

a bit of a lift upwards would have helped. It all just about

holds together, but not with any great feel of security, up

until a rather gnarly bar at 4:34, where variance of opinion

in intonation between the two harps is spotlit. I do love the

sonorities of the chorale 7:19 into the final movement, and

the power of the build up and climaxes further along are really

terrifying. The Russian bass at the bottom of that choir really

draws the ear as it enters at 21:11, and if you can stand wide

vibrato that crucial soprano solo is nicely taken. The final

section is however unfortunately almost entirely taken over

by wobbly vibrato, to the extent that it is hard to hear which

notes the soloists are singing at times. I’m sure the dark colour

of that choir isn’t quite what Mahler would have had in mind,

but its colour does make this performance distinctively Russian

– at the very least it’s quite a few degrees more interesting

than anything Gilbert Kaplan managed to achieve, even with the

Vienna Philharmonic at his disposal. You’ll be glad to hear

the organ is present at the final climax, but no-one can, or

indeed dares to top that lead trumpet. It’s all a bit edge-of-the-seat,

but in the end the pluses outweigh the minuses, even though

the hairs might rise at the back of your neck for reasons other

than normal.

The soft spot I have for the second symphony is replaced by

something of a blind spot for the daunting mound of music which

is the Symphony No.3. Svetlanov’s is an impressive recording,

not without a few relatively minor blemishes, but I enjoyed

the first three movements immensely. I was expecting to be challenged

once again by the fruity vibrato of the alto in ‘O Mensch! Gib

acht!’, but was instead pleasantly surprised by some nicely

accompanied and sensitive singing. The Russian quality of the

vocal elements, choral and solo, are more emphasised in “Bimm,

bamm”, but this is more an aspect of character rather than a

criticism. The opening of the final movement is done with moving

expression, and with only some minor brass intonation issues

the penultimate tuttis and final climax are rich and powerfully

effective. This is a recording which has made me re-consider

my views on Mahler’s Symphony No.3, and for this my gratitude

goes to Svetlanov and his Russian players.

The Symphony No.4 is lighter in character, though Svetlanov’s

tempo in the first movement lends itself more to Tchaikovskian

expression rather than that pastoral jauntiness which it can

have. This is nicely played however, and the transparent textures

of the second movement are also managed well, a few moments

of dodgy intonation aside. There is a nice sense of romantic

sweep to the movement as it takes off around 6:30 in, and the

violin slides are shamelessly juicy. The Ruhevoll third movement

is marked as ‘poco adagio’, but Svetlanov takes it as a real

adagio, sustaining to good effect and arguably lingering a little

too long in places, though his timing is the same almost to

the second as Bernstein’s 1987 Concertgebouw recording on DG.

Collective string discipline is an issue at places, the slides

at 5:30 being a case in point. Natalia Gerassimova’s solo in

the final movement is rather close and not comfortably natural

in the balance. With the entire orchestra almost obscured behind

her voice it’s hard to warm to this part of the recording, although

the performance is able enough.

Ever popular, and with that bite which makes Mahler stand out

from the crowd when it comes to turn of the century romanticism,

the Symphony No.5 drags a little at the opening with Svetlanov,

though once again his timing agrees with Bernstein’s Vienna

Philharmonic version on DG. The music should indeed have a weighty

funereal feel, and Svetlanov very much gives us that heaviness

of tread – the long journey rather than any feeling of imminent

arrival. Where the tempo picks up at 6:20 the first trumpet

unfortunately takes over again, blisteringly distracting us

from the rest of the orchestra and providing it with the extra

colour of a New Orleans jazz band. The second movement Stürmisch

bewegt is given plenty of vehemence as indicated in the score,

and the playing is strikingly energetic and stormy for the penultimate

passages. I quite like the character of the Scherzo, which takes

the nicht zu schnell marking seriously and is generally more

concentrated than convivial. The orchestra makes a fine sound

here, held together by a strong horn section. The famous Adagietto

is played with satisfyingly full and warm expression, though

the strings can be a touch ragged between notes when exposed.

I’ve heard that vigorous counterpoint a few minutes into the

fourth movement done a little more cleanly, but it will do.

The main body of the movement is effective enough, the brass

cutting through triumphantly and the vast swings of contrast

and texture take with deftness and even some wit at times.

The Symphony No.6 returns us to that drier balance we had with

the first symphony, and the opening is rather stodgy and earthbound.

This is the first of the symphonies Svetlanov recorded, and

Nina Svetlanova’s booklet notes indicate he was ‘virtually the

first Russian conductor to perform Mahler’s symphonies in the

West’. There are those who have pointed out that the Russians

still had a great deal to learn about conducting Mahler at the

time, but aside from being a bit opaque and disconnected in

terms of recording quality this first movement could have been

worse. The second movement Scherzo takes off at a terrific pace,

pretty much ignoring the ‘pesante’ marking. The orchestra copes

well enough, but is sounds too much hacked-though at critical

points to be really effective. The Andante moderato is OK, but

a bit too rough around the edges to stand as a contender. Around

6:40 is a section which sums this up, with a cheesy and unsubtle

triangle, and cowbells which sound more like a child’s toy than

the real thing. The Finale has some impressive drum thwacks

and other good moments, but little irritation such as the suspect

brass intonation in those outbursts in the third minute remove

what is left of the gloss on this recording. Someone coughs

at 2:50 and 4:00 as well, which is a surprise, as we’re not

told that this is a live recording. The applause at the end

clinches it. There is plenty of drama here, but not enough magic

to contrast with the rest, so while this 6 would have made for

a good concert it remains low in the pecking order for this

set as a whole.

The vast Symphony No.7 fares better as a recording, though is

a trifle distant and generalised. The opening Adagio is a rather

lumbering and baggage-laden affair, but we are picked up by

a bracing Allegro con fuoco which has positive aspects. Intonation

in exposed regions is a problem yet again in this movement,

with a ‘low’ high note in the brass at 12:42, given the lie

by an in-tune trumpet entry on the same note at 14:57. I can

but imagine the dirty looks exchanged. Ragged strings and a

loss of direction follows this, and I’m can’t say I was filled

with confidence for the rest of this musical journey. The 1ste

Nachtmusik is I’m afraid rather formless, Svetlanov’s grip on

the fragile textures and material of the music more like a roaming

rehearsal run-through than the definitive result of intense

preparation. The Scherzo is a little firmer, though I’m intrigued

as to who though the elephantine tuba entries at 1:25 where

a good idea. There is a deal of wit in the detailed orchestration

to this movement, though the somewhat vague recording quality

misses a certain amount of this. The 2nd Nachtmusik

passes without any great traumas, though makes little impression

one way or another. The final Rondo blazes impressively and

with a massive drum sound, and the movement is fine enough in

its own rough-hewn way, though the bells at 10:52 and 16:30

seem more to announce the arrival of a train than represent

any grand celebratory gesture. Disc 11 is further filled with

the Adagio which was to have been the first movement to the

incomplete Symphony No.10. This is a fine performance about

which I have few complaints, though it is a fair bit slower

than most and does drag on somewhat, and some daft violinist

anticipates at the big chord at 23:35 like a musical sneeze.

If the Symphony No.3 was a bit of a blind spot for me, Mahler’s

Symphony No.8 is a bridge I’ve rarely crossed with equanimity.

Whether you hear it as a sublime and magnificent creation or

a grossly overblown statement of unmanageably melodramatic proportions

and intent, this performance and recording is here to convince

one of emphatically its validity and worth. I have to admit

Svetlanov is quite in his element with these huge works, and

the ‘Russian’ line which also takes us into the grander and

more sprawling symphonic works of someone like Shostakovich

can be heard like a sort of pre-echo in elements of the ‘Symphony

of a Thousand’. Yes, the singing isn’t universally beautiful,

but the choral moments are genuinely powerful and the orchestra

rises to the challenge most of the time. The soloists are as

usual liberal with the kind of vibrato which normally puts me

off my hot chocolate of an evening, but here seems to suit the

music and the proportions and scale of the performance entirely.

Of these the men are most extreme. If set a solfège test to

write down which notes the tenor Alexei Martynov was singing

in the 15th minute of Part II, or those of baritone

Dmitri Trapeznikov immediately following, then I would fail

miserably. Each movement is on a separate disc and with no further

access points, which may be considered an inconvenience.

To my mind, the Symphony No.9 is Mahler’s masterpiece, and any

recording has to be pretty hot to contend with the myriad competition

available these days. Svetlanov’s recording has a funny quality

which gives parts of the orchestra a strangely boxy sound and

has rather an unnatural stereo picture. If this doesn’t disqualify

it immediately it certainly makes it harder to evaluate in terms

of artistic quality, especially for a headphone user like myself.

There is not a great deal wrong or right with the first movement.

The notes are all there, but it is full of weird moments and

while I can’t say it held my attention particularly closely

it does hold a kind of ‘horror’ fascination. A funny imbalance

between left and right channel doesn’t help, and on a variety

of systems I couldn’t quite reconcile the volume in the left

channel with that of the right. The whole thing has a pioneering

1950s ‘adventures in stereo’ feel about it, and the really clunky

moments like those in the tenth minute of the first movement

are certainly not helped by the recording balance. The third

movement is taken at a fiery pace which the orchestra can only

just keep up with, so that’s pretty much a no-go area. The final

Adagio has redeeming qualities and I love those expressive horn

solos at 2:40 and 6:45. On the strength of this I think we should

start a ‘campaign to bring back vibrato in French horns’. Impassioned

strings and some moments of fine playing bring thus cycle to

a respectable and at times noble close, but the phasey nature

of the recording was turning my brain a funny colour by the

end. This issue is perhaps not such a problem on speakers, but

there shouldn’t be any limitations in this regard so no genuine

Brownie points for this Mahler 9.

To conclude, this cycle of Mahler symphonies was never likely

to be an all-round champion, but did promise a different view

on the pieces which, to a certain extent, it does. Part of the

problem is price, which seems rather high for a re-issue at

well over 50 GBP at the time of writing. You can have Haitink

and the Concertgebouw on Philips or Rafael Kubelik on DG for

about the same price, half a dozen excellent alternatives which

undercut these, and Sir Simon Rattle on EMI for less than half.

Admittedly my main comparative reference, that with Leonard

Bernstein on DG, is also rather pricey, but does include all

the orchestral songs and a remarkable standard of orchestral

musicianship, even though you may not agree with everything

Bernstein does with Mahler’s music. Evgeny Svetlanov was always

an impressive conductor, and there are many impressive moments

in this cycle. Unfortunately it has been left behind in every

regard by one or other of the more recent alternatives, and

also has to stand up to challenges from classic versions at

lower price, so I certainly can’t recommend it as a first choice.

Patchy intonation issues and some substandard playing and ensemble,

a few cases of odd recording balance and wobbly singing all

tell against, which is a shame since at its best this is a cycle

which does have quite a lot to offer. I doff my hat to Svetlanov

for winning me over to Mahler’s Symphony No.3, and, with regret,

move on.

Dominy Clements

Full listing

Gustav MAHLER (1860-1911)

The Symphonies

CD 1

Symphony No. 1 (1884-96) [56:55]

CD 2

Symphony No. 2 “Resurrection” (1888-94): I-III [45:57]

CD 3

Symphony No. 2 “Resurrection” (1888-94): IV-V [41:52]

CD 4

Symphony No. 3 (1895-6): I-II [43:39]

CD 5

Symphony No. 3 (1895-6): III-VI [53:16]

CD 6

Symphony No. 4 (1899-1901) [60:33]

CD 7

Symphony No. 5 (1901-2) [72:57]

CD 8

Symphony No. 6 (1903-05): I-II [35:11]

CD 9

Symphony No. 6 (1903-05): III-IV [44:42]

CD 10

Symphony No. 7 (1908): I-IV [67:27]

CD 11

Symphony No. 7 (1908): V [17:52]

Symphony No.10: Adagio (1910) [31:46]

CD 12

Symphony No.8 (1909): I [24:13]

CD 13

Symphony No.8 (1909): II [59:20]

CD 14

Symphony No. 9 (1909) I-II [75:48]

|

|

|