|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

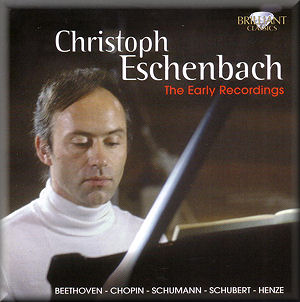

Christoph Eschenbach: The Early

Recordings

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37 (1801) [38:14]

Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat major, Op. 73, “Emperor” (1809) [40.07]

Piano Sonata No. 29 in B flat major, Op. 106, “Hammerklavier” (1818)

[49:54]

Frédéric CHOPIN (1810-1849)

Preludes, Op. 28 (1839) [40:55]

Prelude in C sharp minor, Op. 45 (1841) [6:10]

Prelude in A flat major, Op. posth (1834) [0:39]

Robert SCHUMANN

(1810-1856)

Kinderszenen, Op. 15 (1838) [19:43]

Franz SCHUBERT

(1797-1828)

Piano Sonata in A major, D959 (1828) [40:04]

Piano Sonata in B flat major, D960 (1828) [43:15]

Hans Werner HENZE

(b. 1926)

Piano Concerto No. 2 (1967) [49:18]

Christoph Eschenbach (piano)

Christoph Eschenbach (piano)

London Symphony Orchestra/Hans Werner Henze (Beethoven, Op. 37;

Henze); Boston Symphony Orchestra/Seiji Ozawa (Beethoven, Op. 73)

rec. December 1971, Fairfield Hall, Croydon (Beethoven, Op. 37);

October 1973, Symphony Hall, Boston (Beethoven, Op. 73); June 1970,

Bavaria Studio, Munich (Beethoven, Op. 106); October 1971, Tonstudio,

Berlin (Chopin); May 1966, Beethovensaal, Hanover (Schumann); April

1973, Studio Lankwitz, Berlin (Schubert, D959); April 1974, Jesus-Christus

Kirche, Berlin (Schubert D960); April 1970, Wembley Town Hall (Henze)

BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9189 [6 CDs: 78:21 + 49:54 +

67:27 + 40:04 + 43:15 + 49:18]

BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9189 [6 CDs: 78:21 + 49:54 +

67:27 + 40:04 + 43:15 + 49:18]

|

|

|

Christoph Eschenbach is currently Music Director of the National

Symphony Orchestra in Washington, having held similar posts

in such places as Houston, Philadelphia and Paris. Since the

early 1970s his career has centred around conducting, and this

modestly priced collection is a timely reminder that he originally

made his reputation as a pianist.

Record companies sometimes make things easy for us. The booklet

notes by Ates Orga accompanying this box sometimes quote from

original reviews, giving us an idea what to think even before

we hear the performance. Trevor Harvey, for example, writing

in the Gramophone in 1972, heard “penetrating insight and brilliance”

in Eschenbach’s performance of Beethoven’s C minor concerto,

but found the conductor’s contribution – Hans Werner Henze,

no less – “often sluggish”. Getting on for forty years later,

I can only agree with the first judgement as much as I disagree

with the second. I was fascinated to hear what kind of a showing

Henze would make as a conductor in such a work. The very opening

is smooth and soft-grained, and the orchestral sound is more

early Romantic than anything Classical. But to my ears the playing

and the pacing of the music is full of character, and when the

orchestra is given a purely subsidiary role the conductor and

soloist are as one. This is a lyrical view of the concerto,

less severe than many readings. A certain over-emphasis when

accents are marked in, both from the soloist and the orchestra,

is the only point which disturbed me, and this is emphasised

by a close recording. Otherwise I found this a most satisfying

performance.

I’m not usually an admirer of Ozawa, especially in the Viennese

classics, so I had some misgivings before hearing the performance

of the “Emperor Concerto”. I was wrong. The orchestral contribution

is quite superb, unanimous, very subtle in accompanying passages.

Just listen how the Boston players tuck in to the first movement

tutti. Ozawa even manages to make something significant out

of the inner strings scrubbing figures! Eschenbach is magnificent,

strongly assertive where necessary, and, like his orchestra,

highly sensitive in the moments when he accompanies orchestral

solos. The second movement is very slow and tender, but otherwise

the tempi do not draw attention to themselves. My only negative

reaction rather confirmed my feelings about the C minor concerto,

a certain harshness of tone, a hammering quality in louder passages

such as the thundering octaves at several points in the first

movement. The recording is superbly full, rich and detailed,

but there are at least two clumsy edits, one example at 5:26

in the first movement so grievous that one wonders how it was

allowed to pass.

I think the maxim “Life’s too short” will prove sadly true in

respect of my ever making my own analysis of the fugal finale

of the “Hammerklavier” Sonata. No, I’ll just have to be satisfied

by the sense of awe this work always provokes in me, first at

the composer’s extraordinary vision and second at the audacity

of any pianist attempting to play it. Eschenbach’s performance

is a very satisfying one, and since the opening demonstrates

the two main drawbacks I found with the performance it makes

sense to dispose of them straight away. First, he is quite free

with the pulse here, and whilst the this opening is certainly

very commanding, a real call to attention, the various liberties

the pianist takes with pulse and metre do not always sound completely

natural or convincing. And then there is the player’s tone.

The word “clangy” is hardly a pretty one, but it quite satisfactorily

describes the sound of the piano in louder passages here, and

since I have already alluded to it in my comments on the concertos

I can only assume that Eschenbach – whom I have never heard

live – employs a massively percussive technique in louder passages

which may please some but which disturbs me. That said, this

first movement is full of drama. I found the tiny – in comparison

– scherzo just right, the tempo skilfully judged and the off-beat

rhythms perfectly executed to deceive the ear. The heart of

the sonata is the extraordinary slow movement, and I can think

of no higher praise than to say that Eschenbach’s intense, rapt

performance, at one of the slowest tempi I have heard, held

my attention throughout. This is almost unique in my experience

in this movement which I always find a personal challenge as

a listener. Textures are beautifully clear, notably in the passages

for crossed hands. The finale generates enormous cumulative

power and excitement and is perfectly satisfying on its own

terms, though I am once again intermittently troubled by the

sound.

I’m less convinced by Eschenbach’s Chopin. Sheer power is less

in order here, of course, but even so there are moments – such

as the rapid repeated notes and octaves in the fifteenth prelude

– where the sound is less than lovely. Otherwise there is bravura

and splendidly clear virtuosity in plenty. The following prelude,

for example, in B flat minor, is technically brilliant at a

breathtaking speed. But the last prelude of all points up what

is missing. It is again brilliantly played, but the score is

marked appassionato, whereas this reading seems distant, cold

and certainly not passionate. And where is the poetry that one

associates with the Chopin playing artists such as Rubinstein

or, more recently, Ingrid Fliter. The Chopin is preferable,

though, to the Schumann, which will bring pleasure to few, I

fear. These pieces are on the whole hard driven and communicate

very little notion of childhood, either real or remembered.

The fifth piece, “Glückes genug”, contains no dynamic mark higher

than piano, though you’d never realise it from this performance.

In the following “Wichtige Begebenheit” Eschenbach surely goes

too far in his reading of the accents, and the well-known “Träumerei”,

a most touching piece when given simply and at face value, is

excessively romantic and dragged out. In general, the gentle

pieces are too overtly expressive and the more turbulent ones

too forced and violent. To all that must be added the two seconds

of silence – all ambient noise suppressed – between each piece,

effectively killing what little atmosphere the pianist has been

able to create.

The two Schubert sonatas will, I think, provoke mixed reactions

from listeners. If you like Schubert straight, classical, with

the bare bones of the score presented, as it were, without commentary,

then you might well enjoy these performances. But if – like

me – you think Schubert can stand a bit of interpretation, that

the romantic side of his nature should come out, you might find

them a bit wanting. And then I come back to the thorny question

of the sound the pianist was making at this stage of his career.

Other pianists manage to make the opening of the A major sonata

arresting enough without quite such harsh accents and percussive

sound. Greater flexibility of pulse, too, is needed to express

the essential Schubertian grace. Eschenbach’s playing is most

beautiful in the beguiling second subject group of this first

movement, but as soon as the accent changes to something more

demonstrative, so does the instrumental colour. The development

section of this same movement features a series of repeated

chords in the accompaniment. When these chords pass into the

right hand they are unpleasantly hammered out, and when the

opening music returns the effect is one of anger rather than

something majestic. The closing bars, however, are beautifully

done. In short, a too-literal approach to anything above forte,

plus a rather rigid attitude to pulse, make for Schubert rather

short on charm.

I was much more taken by the B flat Sonata. The very opening

is as close to Olympian calm as can be imagined, very beautiful

indeed. When this wonderful theme is repeated, forte, I feared

the worst, as the hammering tone reappeared. But gladly the

work allows for far less of that forced, hectoring quality;

on the contrary, it requires the pianist to play with sweetness

and delicacy. The first movement is unsurpassed for caressing

tenderness. The second movement is very slow indeed, a challenge

to performer and listener alike. The scherzo and trio are insouciant,

just as they should be, and the finale – with the exception

of two fortissimo outbursts – chatters along in a satisfyingly

congenial way. The emotional world the work inhabits is well

evoked too. The first and last movements are equivocal. Those

low, left hand trills in the first movement, what do they mean?

And the sudden silences in both movements? The octave which

opens the finale and which is used to such curious and disturbing

effect in the passage before the final coda? Eschenbach places

these events before us in a masterly way, creating just the

right balance of classical restraint and overt Romantic expressiveness.

Schubert gives no answers, and Eschenbach simply acts as his

most eloquent advocate.

The odd-man-out of this collection is the Second Concerto by

Hans Werner Henze. In three movements played without a break,

the work lasts for almost fifty minutes, roughly the same length

as another second piano concerto, that by Brahms. It was composed

for Eschenbach. It is in no sense a traditional piano concerto.

Although many passages must be phenomenally taxing to play,

there is no virtuoso display for its own sake, and no sense

of struggle for dominance between the soloist and the orchestra.

For much of the time, especially in the first movement, the

piano barely asserts itself as an important solo element. This

first movement is predominantly slow, made up of fragments of

melody and with much figuration in the solo part. The thunderous

final bars seem unjustified by what has gone before, and lead

directly into a scherzo which is grim indeed, though undeniably

exciting for much of the time. There are slower passages and

others which have a cadenza-like feel about them. The finale

is in several sections, the first of which, according to Eschenbach,

features “a new style of piano writing” exploiting the pianist’s

ability to spin out long legato lines over long periods of time.

I can’t hear this myself, I confess. There are a couple more

ear-splitting moments, including the final crescendo, but the

work as a whole leaves a sombre impression, even a certain greyness,

and I can’t help wondering how many times Eschenbach, or any

other pianist, has been able to programme it since it was first

given in 1968.

William Hedley

|

|

|