|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

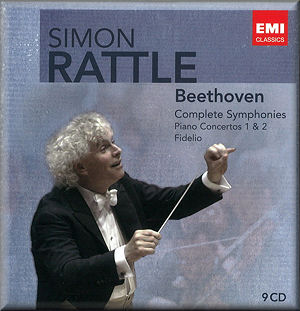

Ludwig van

BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Symphony No. 1 [25:31]

Symphony No. 2 [32:08]

Symphony No. 3 [49:46]

Symphony No. 4 [33:52]

Symphony No. 5 [31:57]

Symphony No. 5 [31:46] *

Symphony No. 6 [44:41]

Symphony No. 7 [39:59]

Symphony No. 8 [25:56]

Symphony No. 9 [69:57]

Piano Concerto No. 1 (cadenzas by Beethoven) [37:14]

Piano Concerto No. 1 (cadenzas by Glenn Gould) [34:45]

Piano Concerto No. 2 [28:48]

Fidelio (1814) [110:00]

Lars Vogt (piano)

Lars Vogt (piano)

Barbara Bonney (soprano), Birgit Remmert (alto), Kurt Streit (tenor),

Thomas Hampson (baritone)

Leonore (mezzo) – Angela Denoke; Florestan (tenor) – Jon Villars;

Don Pizarro (baritone) – Alan Held; Rocco (bass) – Laszlo Polgar;

Marzelline (soprano) – Juliane Banse; Jaquino (tenor) – Rainer Trost;

Don Fernando (bass-baritone) – Thomas Quasthoff;

Arnold Schoenberg Choir; Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (Fidelio)

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (symphonies)

City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (concertos)/ Sir Simon Rattle

City of Birmingham Symphony Chorus/Simon Halsey

rec. live, Musikverein, Vienna, December 2000, *Musikverein, Vienna,

April-May 2002, Butterworth Hall, University of Warwick, October

1995 (concertos) Philharmonie, Berlin, April 2003 (Fidelio)

EMI CLASSICS 4575732 [9 CDs: 10:00:00]

EMI CLASSICS 4575732 [9 CDs: 10:00:00]

|

|

|

This is the latest and, they tell us, the last of EMI’s Simon

Rattle Edition, gathering together the conductor’s complete

forays into certain composers and repertoire. As with any such

project the sets hitherto released have contained both treasures

and duds. Even though not everything here is perfect, this set

sends the series out on a high with his complete Vienna recording

of the Beethoven symphonies.

Not everyone has been convinced by Rattle’s 2002 Beethoven set,

but I admit that I was sold on it from the start. Repackaged

here at bargain price, even if the documentation is minimal,

it makes an outstanding bargain and a fantastic purchase. The

keynote of the set is energy: pulsating, crackling, electrifying

energy. Rattle’s white-hot vision injects these scores with

a level of vigour that I have seldom heard elsewhere on disc.

In particular he relishes the punch and excitement of Beethoven’s

rhythms. Unsurprisingly this approach works best in the Seventh

where the relentlessness of the beat bounds off the page. The

Scherzo, in particular, is unstoppable, while the first movement

is expansive and majestic in its control. Ineluctable, unarguable

logic characterises the unfolding of the Allegretto, secure

in pacing and awesome in its scale, though next to all this

the opening of the finale comes across as surprisingly slow.

This approach also works brilliantly in the early works, particularly

the Second which here comes across as a work of fully

mature genius. The first movement positively crackles, recreating

for me the infectious excitement of discovering these works

– of hearing them for the first time. Similarly, the finale

positively leaps out of the speakers, while the Larghetto

is beautifully judged and gorgeously played. The First

too is full of bustling energy and the Andante is taken

at a fair lick, though this isn’t something Rattle does in all

slow movements. In fact his attitude to period practice on the

whole is fairly à la carte. The VPO’s playing is often

brisk and transparent in the manner of smaller period bands,

but there is no hint of the hair shirts that some period practitioners

bring to this music: Rattle is happy to broaden out and revel

in the beauty of the sound at key moments. On the other hand

the playing is not just homogenous post-Romantic soup; there

are plenty of moments that make you sit up and take notice as

a particular element is highlighted by a touch such as vibrato-less

strings, braying brass or occasional sforzandi. It is

the selectiveness of these touches that makes them effective,

meaning that for most middle-of-the-road listeners they will

find this something to enjoy rather than to distract. As for

the quality of the instrumental playing, with an orchestra of

this stature it is outstanding. I could pick out occasional

moments that stand out for their extra-special quality – the

solo winds in the slow movement of the Fourth, for example

– but there would be too many to make this a useful exercise.

Discovering them for yourself is one of the great joys of this

set.

What about those craggy masterpieces in the middle of the cycle?

Be satisfied that in Rattle’s hands they are not merely safe;

they are towering. He gives us an Eroica of stature and

power. The playing carries tremendous weight and scale: this

is clearly a symphony orchestra we are listening to.

It also feels very live with its minor fluctuations of tempi

and the sense of a conductor straining at the tiller to keep

the great ship on course. There is an almighty sense of build

to the funeral march while the scherzo romps along with titanic

energy. The finale unfolds with logic and argument and the tempo

broadens out majestically (and surprisingly) for a coda which

marks a fitting culmination of not just the movement but of

the entire work. The Fifth is vibrant and dramatic, the

first movement incisive and visceral, while the finale blazes

with a white-hot sheen. As a bonus we are also given Rattle’s

earlier (2000) account of this symphony with the same orchestra.

It’s interesting to compare the two, but the 2002 account is

easily finer: it’s more dramatic, more live and has a better

recording to help it on its way. Only in the transition to the

finale and the emergence into sunlight at the start of the last

movement does it start to rival the later set.

Only in the Pastoral does Rattle’s preference for the

dramatic develop into a problem, the first two movements sounding

taut and even a little strained in places. Things improve after

this: the peasant wedding fairly frolics along and, after a

terrifying storm, the shepherds’ hymn is broad and expansive.

The Eighth, too, is relatively light on its feet with

a satisfyingly big sound to its first and third movements and

plenty of tongue-in-cheek humour to the second and fourth.

Rattle’s Ninth is evidently the climax of his cycle,

not just chronologically but emotionally. Everything here seems

calculated to produce an impact of shattering grandeur, from

the first, stunning emergence of the opening movement’s main

theme through to the headlong dash for the finishing line of

the finale. Not everyone will love it: some will find his selective

pauses irritating and others will quibble with his tempi and

use of stresses, but I was fully convinced. The Scherzo bounds

along with titanic power and, after this, the expansive tempo

of the Adagio sounds daring and inventive. The finale

comes with its own sense of scale, but Rattle’s pacing and control

of the transitions allows it all to unfurl in a way that sounds,

to me, unarguable. He is helped by a top-notch team of singers.

His old friends from the CBSO Chorus guest star, demonstrating

that they have lost none of the power that so distinguished

his Mahler recordings, and his soloists are as starry a team

as one could imagine. Thomas Hampson sings with poetry and refinement,

not just gusto, and both ladies bring lyricism and breadth to

their music. Kurt Streit, too, sounds convincingly perky in

his “Turkish” episode.

So where does Rattle’s Beethoven set sit in the overall scheme

of things? To my mind he carries the best of the old and the

best of the new. He has a sense of structure and scale that

harks back to Furtwängler and Karajan, while his lithe sense

of movement contains the best of the period movement heard in,

say, Norrington and Gardiner. It’s probably still true that

the conductor who best encompasses both of these worlds is Harnoncourt

in his set with the Chamber Orchestra or Europe, but Rattle’s

sound is bigger and somewhat more Romantic. I recommend his

set to anyone who hasn’t planted his flag squarely in the camp

of either extreme. I certainly wasn’t disappointed.

The symphonies are undoubtedly the main reason for acquiring

this set, but the other items are of value too. The CBSO plays

with some fitting period (vibrato-less) twang for much of the

two concertos, and Lars Vogt scales back his often big-boned

playing to accompany in a style that is utterly sympathetic.

Again, though, there is no hair-shirted asceticism in either

orchestra or piano and this is still a performance of red-blooded

vigour. Vogt plays like the master we know he is, and the cadenzas

tickle the listener’s ear suggestively. As another bonus we

are given two versions of the First Concerto: it’s the same

recording but in one version we get Beethoven’s cadenzas and

in the other those of Glenn Gould. Gould’s cadenza for the first

movement is witty and almost Bachian and it works tremendously

well, but his version is too frenetic in the finale, which Rattle

already paces with frantic busyness. Still, it’s an interesting

comparison. I wonder if this was the beginning of a complete

set that never emerged? A pity, but then Rattle’s later achievement

with Brendel takes some beating.

I have already written about Rattle’s Fidelio

elsewhere in these pages. There’s really nothing to add to that,

save to say that after a gap of a couple of years Rattle’s conducting

seems less wilful and Denoke’s Leonore a little more amenable,

but this performance still can’t hold a candle to the likes

of Bernstein or Klemperer.

So if this is the last instalment in EMI’s Rattle edition then

they have gone out on a high. Rattle flowered later in Beethoven

than he did in, say, Mahler or Britten, but for me the results

are every bit as satisfying and deserve comparison with the

best. Throw in the super budget price and the decision makes

itself.

Simon Thompson

|

|

|