|

|

|

CD: AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

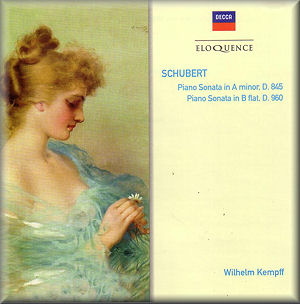

Franz SCHUBERT (1797-1827)

Piano Sonata No. 16 in A minor, D. 845 (1825) [34:41]

Piano Sonata No. 21 in B flat major, D. 960 (1828) [35.56]

Wilhelm Kempff (piano)

Wilhelm Kempff (piano)

rec. Decca Studios, West Hampstead, London, November 1950 (D. 960)

and March 1953 (D. 845)

DECCA ELOQUENCE 476 9913 [70:45]

DECCA ELOQUENCE 476 9913 [70:45]

|

|

|

The Eloquence catalogue is an extraordinarily

rich collection of archive material, and fortunate indeed is the

person responsible for compiling it. I want that job! I reviewed

recently a disc of Arthur Grumiaux playing the Berg Violin Concerto,

and that is only one example chosen from countless indispensable

discs available at an almost laughably low price. And if not all

the issues are of such importance – how could they be? – each

one has some serious claim on the collector. Here we have Wilhelm

Kempff playing two Schubert piano sonatas in recordings originally

issued on Decca. The A minor Sonata has apparently been issued

on CD before, but this is the first appearance on CD of the B

flat major. Neither performance should be confused with the pianist’s

later recordings, a complete cycle recorded by Deutsche Grammophon.

The sound is inevitably showing its age, particularly in louder

passages where there is some distortion, harshness and congestion.

The playing completely eschews any suggestion of sensationalism.

It is sober, considered, weighty and serious. The pianist seems

to lay the music before the listener in an almost dispassionate

way, inviting us to make of it what we will. I feel this particularly

in the first movement of the A minor sonata, where the often sparse

textures, uncompromising as they are, are allowed, as it were,

to speak for themselves. Indeed, there is very little that can

be termed interventionist in these performances. Yes, he makes

a slight accelerando in the final bars of this same movement,

but that is little more than a nod in the direction of surface

drama, and the development section is almost classical in its

emotional restraint. It is more fruitful for the listener to seek

out the subtle differences in phrasing and dynamics in the repeats

of the variations in the slow movement than it is to search for

drama in the scherzo. The lilting, lulling trio is most affectingly

done, however. The extended two-part writing in the finale is

again presented to the listener unadorned, and here one might

wish for something more impetuous, more passionate, though Kempff

royally does the honours in the very final bars.

The sublime opening of the D. 960 sonata is wonderfully poised

in Kempff’s hands, which makes it all the more of a pity that

the sound is so poor here. This is due, I imagine, to deterioration

of the master tape, and it settles down after only a few bars.

All the same, there is a fair amount of background noise and print-through

from the original tapes, and fortissimo passages, particularly

the two in the finale, make for less than comfortable listening.

Kempff is quite free with pulse in the first movement, markedly

more romantic in his approach here than he was in the earlier

sonata. This is a view with which I concur in this most songlike

of sonata movements. He does not observe the exposition repeat,

which for some will be a relief – the movement is already a very

long one – but for others will be a serious drawback, bearing

in mind that this means omitting nine bars of music that Schubert

composed expressly for the purpose, and which features, incidentally,

one of the low, left-hand trills that occur throughout the movement.

The slow movement is beautifully played in Kempff’s now familiar,

rather straightforward – though far from anonymous – manner. The

scherzo, too, is similarly clear-cut, and here as elsewhere one

admires the pianist’s skill in bringing out melodic lines while

never allowing the often repetitive accompanying figuration to

sink into insignificance. Kempff launches the finale at a tempo

as rapid as one is likely to hear it nowadays, and the effect

is robust rather than playful, a perfectly valid view given the

triumphant close, though the final crescendo can hardly

be said to begin piano as the score demands.

Admirers of Wilhelm Kempff, who died only in 1991 at the age of

ninety-five, will want this issue, particularly for the otherwise

unavailable performance of the D. 960 Sonata. Schubert lovers,

too, will welcome the serenity and wisdom of Kempff’s Schubertian

vision. The pianist made a more beautiful sound than one gathers

from this disc, and those for whom this is an important consideration

will prefer to seek out one of the many more recent performances.

The historic nature of these performances makes comparative listening

irrelevant, and the quality of the readings is in any event beyond

serious criticism.

The attractiveness of this issue is enhanced, as is customary,

by a friendly, readable and informative booklet note by Jed Distler.

William Hedley

|

|