|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

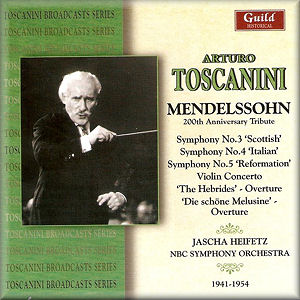

Felix MENDELSSOHN

(1809-1847)

Symphony No.3 in A minor, Op.56 Scottish (1842) [32:42]

Symphony No.5 in D, Op.107 Reformation (c.1840) [26:51]

A Midsummer Nights Dream, Op.21 (1829) and Op.61 (1843) -

I. Overture. Allegro di molto [11:43]: II. Song and Fairy Chorus

Ye Spotted Snake [3:46] ¹

Overture - The Hebrides, Op.26 (1832) [9:19]

Overture - Die schöne Melusine, Op.32 (1833 rev 1835)

[8:50]

String Quintet No.2 in B flat, Op.87 - III. Adagio e lento (1845)

[7:54]

Violin Concerto in E minor, Op.64 (1844) [23:39] ²

Symphony No.4 in A major, Op.90 Italian (1833) [25:54]

Edna Philips (soprano) ¹

Edna Philips (soprano) ¹

Jascha Heifetz (violin) ²

NBC Symphony Orchestra/Arturo Toscanini

rec. 1941-54.

GUILD GHCD2358-59 [75:55 + 76:18]

GUILD GHCD2358-59 [75:55 + 76:18]

|

|

|

Though there is nothing new for the Toscanini broadcast collector

in this commemorative twofer, it does handily enshrine pretty

nearly all the conductor’s extant Mendelssohn performances.

Missing is the Octet performance and the 1945 broadcast of the

wind version of the same work’s Scherzo - a rare outing

for that work from anyone at the time.

Under the rubric of the 200th Anniversary of the

composer’s birth this Guild offering is tightly packed,

well transferred, briefly, and usually cogently annotated by

Robert Matthew-Walker, who seems to claim we are hearing the

1938 broadcast of the Italian symphony whereas we are

actually presented with the 1954 broadcast. Maybe he was misinformed,

because the track details are unambiguous on the subject.

As for the Scottish, this was his solitary performance

of it with the NBC, with whom he performs all the broadcasts

here. Malleably intense, harmonic scrutiny tends to win out

over genuine lyricism and there are moments of inflated orchestral

thrust. The second moment is hardly Vivace non troppo

as marked, though it is characteristically exciting, whilst

the slow movement is borne lightly, deftly and relatively quickly.

The NBC flies by the seat of its collective pants in the finale

where articulation comes under pressure. After the disappointment

of the Scottish, the Reformation comes as balm

though it too is not without its idiosyncrasies. The opening

is finely controlled and Toscanini’s control of rubati

is acute. The rhythmic bases of the music are equally well judged,

though it’s certainly not a conventional approach. He

is unusually expansive in the last movement, and this sense

of stately pacing actually brings an increase in tension and

an anticipation of the great chorale that is unleashed at the

optimum moment with no little glory and solemnity. Is this Toscanini’s

best single Mendelssohn performance? I tend to think so. The

Midsummer Night’s Dream music is rather too taut,

and is not really his kind of thing. It’s enjoyable to

hear the brief Ye Spotted Snakes with soprano Edna Philips

piping away.

Piping away is certainly not something that could ever be said

of Jascha Heifetz. He and Toscanini never recorded the concerto

commercially, thank God. The Vilnius wunderkind’s commercial

outings in the work were pretty mediocre (Beecham, Munch) and

his live meeting with Toscanini’s musical son, Cantelli,

was an outright disaster. Breathless swank is the name of the

game for this Toscanini meeting. He relaxes for the slow movement,

it’s true, where one hears Toscanini moaning in sympathy,

but Heifetz makes much of the passagework elsewhere sound like

Rode. The hooded finger position intensifications only make

it the more awful. Toscanini is no better. Fortunately we can

listen to the Italian Symphony in a performance that

doesn’t push the bounds of the music too far. There’s

highly impressive control of localised detail but never at the

expense of the architectural whole. Note the stalking lower

strings in the slow movement and the cumulative fervour of the

finale. The Hebrides is strongly argued with a good atmospheric

quotient, but not at all rigid. And Die schöne Melusine,

whilst quite brisk, is not overstated, its bass line remaining

strongly defined. A most unusual example of inflation comes

in the shape if the slow movement of the String Quintet No.2

in B flat, which allows for rich cantilena.

This is a handy twofer, well transferred. The performances are

predominantly good.

Jonathan Woolf

see also review by John

Sheppard

|

|