|

|

|

Availability

CD/Download: Pristine Classical

|

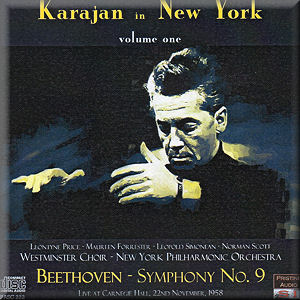

Karajan in New York - Vol.1

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770 –

1827)

Symphony No.9 in D minor, op.125 (1824) [22:08]

Leontyne Price (soprano), Maureen Forrester (alto), Leopold Simoneau

(tenor), Norman Scott (bass), Westminster Choir (director: Warren

Martin), New York Philharmonic Orchestra/Herbert von Karajan

Leontyne Price (soprano), Maureen Forrester (alto), Leopold Simoneau

(tenor), Norman Scott (bass), Westminster Choir (director: Warren

Martin), New York Philharmonic Orchestra/Herbert von Karajan

rec. 22 November 1958, Carnegie Hall, New York, NY, ADD

PRISTINE AUDIO PASC 222 [66:35]

PRISTINE AUDIO PASC 222 [66:35]

|

Availability

CD/Download: Pristine Classical

|

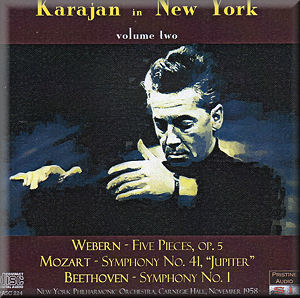

Karajan in New York - Vol.2

Anton

von WEBERN (1883 – 1945)

Fünf Sätze, op.5 (1909) [10:02]

Wolfgang

Amadeus MOZART (1757 – 1781)

Symphony No.41 in C, Jupiter, K551 (1788) [27:50]

Ludwig

van BEETHOVEN (1770 – 1827)

Symphony No.1 in C, op.21 (1800) [22:08]

New York Philharmonic Orchestra/Herbert von Karajan

New York Philharmonic Orchestra/Herbert von Karajan

rec. 15 November 1958 (Mozart and Webern) and 22 November 1958 (Beethoven),

Carnegie Hall, New York, NY, ADD

PRISTINE AUDIO PASC 224 [63:05]

PRISTINE AUDIO PASC 224 [63:05]

|

| |

Karajan meets Murder Incorporated! What a meeting of minds

and sensibilities! Hardly had Leonard Bernstein taken the helm

in New York than along comes this European fellow to conduct

it in Viennese classics – to be honest, the Webern hadn’t yet

become a classic, this was only 13 years after his death and

he was still a seen as a “difficult” composer. Karajan is totally

at home in this repertoire, but he fails to bring to his performances

an old world charm.

As can be expected these are, what we now see as, old fashioned.

Mozart suffers the most with an orchestra which is far too big,

compared to what we are now used to – although it must be said

that the Webern Movements - Pristine calls the work Five

Pieces, which would be Fünf Stücke, but the correct

title is Fünf Sätze, Five Movements - gain in

strength and weight for the use of a large string body. Throughout

there is the heavy hand of “authority”. The tempi are well chosen,

even if the finale is brisk, and there’s never a dull moment,

but Mozart deserves more than this kind of treatment. One wonders

if the inclusion of Ein Heldenleben, in the second half

of this concert, prompted the use of such forces?

The Beethoven performances were given a week later, and what

a change there is in the size of the orchestra and the interpretations

for this concert! The 1st Symphony

has well chosen tempi, and there’s more of a classical feel

to the performance, but it’s still heavy-handed at times and

too strict, with little give and take.

The Ninth is a very fine affair. Karajan has the New Yorkers

breathless, as he launches a first movement of great power,

with a fine Allegro which is a little maestoso;

just what Beethoven ordered. There’s little time for rest here

and whilst Karajan ensures that he has a firm hand on the proceedings,

there’s still an element of real fantasy to the interpretation.

He had me wondering what was going to happen next! The scherzo

is another matter. Although the tempo is well chosen, Karajan

ignores both repeats in the first half, which is odd considering

the composer so obviously wanted the sections to be heard twice;

he wrote twelve first time bars at the end of the second section,

but you cannot play these without playing the first repeat.

It’s all to do with symmetry. In this performance the first

movement plays for 15:07 and the scherzo for 10:40, whereas

if Karajan observed the repeats it would have played for 13:46,

balancing the allegro perfectly, which is what Beethoven

intended. There is another, slight, problem. Once Karajan has

chosen his tempo he’s away but he keeps having to, almost imperceptibly,

slow down to allow for clear woodwind articulation. You will

feel this, and, because he does it often, you will begin to

wonder where the momentum has gone. That said, this is a thrilling

exposition of the scherzo and so good that it makes one

weep at the two miscalculations listed here. The slow movement

is a trifle hard-driven, Karajan refusing to let go and simply

allow the music to play. He builds the climax well, but it is

just a part of the whole, rather than the achievement of musical

discussion. Then we come to the finale, which, for me, is a

real problem. I have two niggles. First of all, Beethoven was

not a vocal composer so his “big tune” works marvellously when

played by the orchestra, but sounds cumbersome when sung. Second,

the tune itself; it isn’t strong enough to carry the kind of

symphonic argument Beethoven is desperate to achieve. As a symphonic

finale it is a failure, for it contains no musical apotheosis,

and after three magnificent movements if any Symphony needed

a really satisfactory musical conclusion, this is the work.

Here, the singers are good – the women are much better than

the men – but never do I feel the sense of exaltation which

is supposed to infuse the music.

Having said all that, these are exciting performances and see

Karajan weaving a little of his magic with an orchestra which

is known for not taking any prisoners; hence its nickname. The

sound is very good, but there is little bloom on the upper string

sound, and quite clear. These two disks are not for general

listening but there is much to enjoy and admire and I am glad

to have them in my collection, even if they couldn’t be my first

choice in any of the works, except, perhaps, the Webern. Well

done, Pristine Audio for giving us the chance to hear a couple

of Karajan’s very rare American appearances.

Bob Briggs

|

|