|

|

|

alternatively

CD: AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

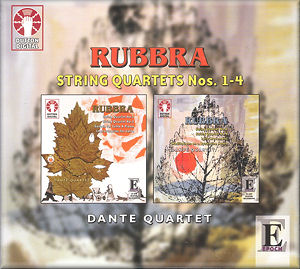

Edmund RUBBRA (1901-1986)

String Quartets

CD 1

String Quartet No. 2 (1951) [23.42]

String Quartet No. 4 (1975-77) [15.03]

Lyric Movement for String Quartet and Piano (1929, rev 1946)

[10.30]

Meditations on a Byzantine Hymn O Quande in Cruce (1962)

[10.25]

Michael Dussek (piano) with Dante Quartet:

Krysia Osostowicz & Declan Daly (violins); Judith Busbridge

(viola); Alastair Blayden (cello); *Krysia Osostowicz & Judith

Busbridge (violas)

rec. Snape Maltings, Suffolk, 14-16 May 2001

CD 2

String Quartet No. 1 (1933-34 rev 1946) [19.56]

String Quartet No. 3 (1963) [20.37]

Improvisation for unaccompanied cello (1964) [6.11]

Cello Sonata (1946) [24.25]

Michael Dussek (piano) with Dante Quartet (Krysia Osostowicz (violin);

Matthew Truscott (violin); Judith Busbridge (viola); Pierre Doumenge

(cello))

Michael Dussek (piano) with Dante Quartet (Krysia Osostowicz (violin);

Matthew Truscott (violin); Judith Busbridge (viola); Pierre Doumenge

(cello))

rec. Henry Wood Hall, London, 14-17 April 2002

Boxed Set reissue of Dutton Epoch CDLX 7114 and CDLX 7123

DUTTON EPOCH LXBOX 2010 [71.41 + 59.13]

DUTTON EPOCH LXBOX 2010 [71.41 + 59.13]

|

|

|

These two discs have now been reissued as a single slip-cased set and a very cogent collection they make too.

The heart of the above pair of discs is the complete string quartets of Edmund Rubbra. This is not the first time they have been recorded as a cycle. In the early 1990s, while Conifer were still buoyant, that company recorded the four in a slackly filled [45:28 + 38:04] two CD set 75605 51260 2. The young quartet involved was the Sterling. The Conifer has now been reanimated and made freshly available by ArchivCD. I half expect it to see it appearing Regis or Naxos.

While the First Quartet is dedicated to Vaughan Williams don't for one moment imagine that it will sound like that composer. That said, there are a few fleeting moments where it coasts close to that green and pleasant land. For the most part though this is of a piece with Rubbra’s First Symphony and then with the much later Piano Concerto. After an insistently morose lento the finale launches one of those typical ostinati over which Rubbra pitches a quick-running vital sinuous tune; this time with much in common with his own Fifth Symphony.

The Second Quartet is in four movements, the first and third being markedly longer than the other two: 8:39; 2:37; 7:31; 3:55. It was premiered in 1952 by the Grillers (whose recording has also been revived by Dutton on CDBP9792). They were the same quartet that premiered Bax's Third in the mid-1930s. The character of the two quartets (Bax’s and Rubbra’s) could hardly be more different: Bax, highly spiced, poetic and dramatic; Rubbra, Beethovenian, earnest, the abnegation of ornament. This monastic severity carries over into the ‘inscape’ of the Cavatina which is an evolution of the adagios of Beethoven's last quartets. There are some lovely things in this quartet but its character overall seems too diffuse - something that cannot be said of Rubbra’s Third.

The Third Quartet was a child (albeit a wise and knowing child) of the 1960s. Intense, grave, dense and then skittish. Overall though this is once again a work of Beethovenian introspection despite an allegro leggiero that flies Tippett-like through the Dark Night of the Soul. It ends with a modestly confident gesture.

Rubbra's last quartet, the Fourth, is dedicated to that other sombre symphonist and quartet writer, Robert Simpson. Simpson, before he fell out with the BBC, was a doughty Rubbra and Brian champion within the Corporation. It was as a result of his ‘street-fighting’ skills that Rubbra managed to secure various symphony broadcasts in the 1960s and 1970s including key broadcasts of the symphonies conducted by Groves (1 and 2) and fellow Northamptonian Malcolm Arnold (3 and 4). The Fourth was premiered by the Amici who were, in 1978, to record Bax's Third Quartet for Lewis Foreman’s Gaudeamus LP label. The Rubbra is in two concentrated movements vital with both dancing and serious material. John Pickard in his liner note reminds us that the themes and their treatment are related to the composer's wonderful Eleventh Symphony - itself a miracle of succinctly communicated drama. In the second movement of the quartet the music rises inexorably to a shiningly substantial and shudderingly heroic statement (5.32, tr.8) before settling into sempiternal silence. The following downward curvature is almost too steep. I do wonder whether that subsiding should have been more protracted. Is this at the door of Rubbra or of the Dantes? Concise expression is the order of the day in the Eleventh Symphony where form and substance are perfectly matched and resolved. Rubbra could have allowed himself more time in the quartet to trace a steady descent to silence - the sort of thing that the usually more discursive Pettersson and Hovhaness managed with a surer touch.

The six minute Improvisation is typically serious Rubbra. It prompts thoughts of the Bach suites for solo cello, of the amber-toned reflections of Bax's Rhapsodic Ballad and, with uncanny closeness, the Finzi Cello Concerto.

The Cello Sonata has that trademark occluded lyricism. It begins with all the potency of Rubbra's beetling Soliloquy (cello and orchestra); recorded by Rohan de Saram on Lyrita and by Du Pré on Cello Classics. Rather like the Improvisation this too might occasionally remind you of the Finzi Cello Concerto both in its singing lines and its Bachian contouring. The movements are laid out: slow - fast - slow.

The Lyric Movement is a single movement piece - the earliest across these two discs. It represents a path that was fully subsumed into his mature style. This is Rubbra in densely pastoral style shadowing the Howells of the Fantasy String Quartet and even more so of the 1915 Piano Quartet. The form is instantly recognisable as a Cobbett ‘phantasy’ although that name does not appear in the title.

The Byzantine Meditation was written for violist Maurice Loban, originally for solo viola. He premiered it in December 1962. Rubbra later arranged it for two violas as featured here. It is the most severe work across the two discs with little in the way of surface attraction or drama. The work owes something to the austere Holst - say in the Lyric Movement for viola and the Four Songs for voice and solo violin although, in fairness, those two works have a more open lyrical heart than this work.

Wonderful discs making conveniently available vibrant and sincerely expressed music of unaffected profundity. The music is well supported in each case by the booklet notes, by performing insight and by a closely engaged recording.

Rob Barnett

|

|