|

|

|

alternatively

CD: AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Download: Classicsonline

|

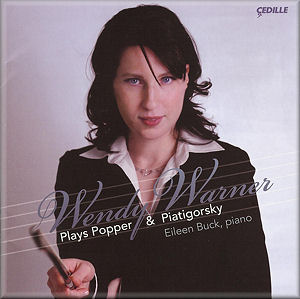

Wendy Warner Plays Popper and Piatigorsky

David POPPER (1843-1913)

Suite for Cello and Piano, Op. 69 [27:34]

Three Pieces, Op. 11 [12:37]

Im Walde, Op 50. [23:06]

Gregor PIATIGORSKY (1903-1976)

Variations on a Theme of Paganini [16:02]

Wendy Warner (cello); Eileen Buck (piano)

Wendy Warner (cello); Eileen Buck (piano)

rec. 27-31 August, 2007 (Popper Opp. 11 and 69), 26-27 June, 2008

(Popper Op. 50 and Piatigorsky), Fay and Daniel Levin Performance

Studio, Chicago, Illinois, USA

full price

CEDILLE RECORDS CDR 90000 111 [79:15]

CEDILLE RECORDS CDR 90000 111 [79:15]

|

|

|

David Popper did not set out to become the Liszt of the cello.

When he arrived at the Prague Conservatory at age 12, in the

year 1855, he was an aspiring violin virtuoso, but the school

had too many violin students and Popper was assigned to cello

lessons instead. “Within a few years”, the booklet-notes for

this new CD tell us, he was “regularly substituting for the

official cello professor”. In a few years more, Popper became

lead cellist of the Vienna Philharmonic. His career as a composer-performer

lasted for several highly distinguished decades.

This disc is my first introduction to Popper, who evidently

wrote four cello concertos (only one has been recorded), a requiem

for three cellos and orchestra, and a suite of forty études

which was recently recorded for Naxos by Dmitry Yablonsky. The

Suite for cello and piano, Op. 69, opens with a memorable

theme in the style of a cheerful Brahms. It is an immediately

appealing piece, with charming melodies at every turn and a

marvelously singing cello part. The best stylistic comparison

I can make is to suggest the very happy combination of Germanic

formal structure and the amiable, tune-laden cheeriness of Popper’s

contemporary and countryman Dvorák. Only in the slow-movement

ballade do clouds appear on the horizon, but the finale dispels

them with rapid, light-hearted passagework for the cello.

The early Three Pieces, Op. 11, are highlighted by a

witty humoresque and a piquant, danceable mazurka. Im Walde,

Op. 50, runs the gamut of typical romantic-era forest images,

from the rhapsodic opening to the “Dance of the Gnomes”, which

features a devilish piano part sounding rather like Schumann,

or Grieg’s “March of the Trolls”. Even amid the gnomes’ revelry,

though, Popper can’t resist inserting a lyrical central passage.

Further highlights of the suite include the soft, reverent closing

of the “Devotion”, the very Dvorákian opening tune of the round

dance, and the whistling cello harmonics which bring the same

dance to its end.

Gregor Piatigorsky is another composer-performer in the Popper

tradition, but from the next century over, and with a greater

emphasis on virtuosic effect. He wrote his Paganini Variations

(yes, they’re on That Tune) in 1946, and each variation is modeled

after the style of a colleague or friend. Some are cellists

– the first variation is Pablo Casals, and the eleventh is Gaspar

Cassadó – but the collection is a diverse one: Paul Hindemith,

Yehudi Menuhin, Nathan Milstein, Fritz Kreisler, Jascha Heifetz

and even Vladimir Horowitz inspired variations based on their

musical personalities. The Kreisler variation is light and frothy,

like one of his encores; the Milstein is a silky-smooth virtuoso

piece at near light-speed; the Horowitz is a highly dramatic

ninety-second crescendo which brings the piece to a forceful

conclusion. All of them are enjoyable, and thankfully Piatigorsky

is quite creative in the ways he chooses to vary this all-too-familiar

theme. I never tired of hearing it crop up again in a new disguise.

Wendy Warner is a superb cellist capable of meeting all of Piatigorsky’s

technical demands. She plays two instruments on this recording,

and the 1772 Gagliano used in the Suite, Op. 69 has a

particularly rich sound. But it is Warner who really shines,

attuning her playing especially well to Popper’s indulgent,

tuneful celebrations of the beauty of the cello’s sound. Listening

to this recording of the Suite, in particular, one can

understand why Pablo Casals remarked that “no other composer

wrote better for the instrument” than David Popper. Neither

Popper nor Warner is capable of making the cello sound ugly.

Eileen Buck deserves credit for her piano accompaniment, too,

although she really only becomes an equal partner in the music

during the Popper “Gnome Dance” and some of the Piatigorsky

variations. She certainly knows when to let the cello do the

work and when to take up the argument with equal force. I wish

I could say the same for the engineers; the piano is rather

backwards in the mix, although this is just taking a cue from

the balance the composers themselves put into place.

One can imagine these performances being bettered some day –

say, with more wit in the fourth movement of Im Walde

or in the humoresque – but the odds are slim, especially because

there are almost no other recordings of this repertoire to speak

of. In my imagination I relish the possibility that Wendy Warner

and Eileen Buck will go on to record several more recitals of

music by these composers. David Popper’s Pieces Opp. 54, 55,

and 64 await, as do his four concertos. More, please!

Brian Reinhart

see also review by Jonathan

Woolf

|

|