|

|

|

AVAILABILITY

Buywell.com

|

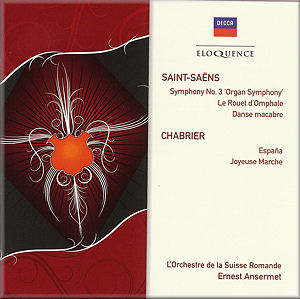

Camille SAINT-SAËNS

(1835-1921)

Symphony no.3 in C minor, op.78 (Organ Symphony) (1886) [37:17]

Le Rouet d’Omphale, op.31 (1869) [8:50]

Danse macabre op.40 (1874) [7:20]

Emmanuel CHABRIER (1841-1894)

España - rhapsody for orchestra (1883) [6:48]

Joyeuse Marche 1888) [3:59]

Pierre Segon (organ) Pierre Segon (organ)

L’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande/Ernest Ansermet

rec. Victoria Hall, Geneva, Switzerland; October 1952 (Saint-Saëns

opp. 31, 40; Chabrier); May 1962 (Saint-Saëns op.78). ADD

DECCA ELOQUENCE

480 0082 [64:43] DECCA ELOQUENCE

480 0082 [64:43]

|

|

|

Some years ago I had a most interesting conversation with a hi-fi

salesman. He told me that, whenever a customer happened to mention

that he had even a passing interest in classical music, the shop

had three pieces of music on CD ready to pop into a machine to

demonstrate its capabilities.

The first was the dramatic climax to the Festival at Baghdad

finale of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade. The

second was the opening to Richard Strauss’s Also sprach

Zarathustra which even quite knowledgeable customers usually

referred to as “the 2001 music”. And the third was

the grandiose finale to Saint-Saëns’ Third Symphony,

a piece that, so he told me, usually drew a small crowd of pop

music fans to listen as they subliminally recalled the “big

tune” from a 1977 hit record (“If I had words to

make a day for you / I'd sing a morning golden and true / I would

make this day last for all time / then fill the night deep with

moonshine...)

That story, though, makes a serious point about the many recordings

of Saint-Saëns’s blockbuster - that it has often been

marketed as a sonic experience rather than as a piece of music.

Ever since 1959 and RCA’s recording with Charles Munch and

the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the Organ symphony has been

seen as something of a sound engineer’s virility symbol.

Far from many critics questioning the musical ethics of Daniel

Barenboim’s 1970s recording in which technical boffins mixed

an orchestral contribution recorded in Chicago with Gaston Litaize’s

organ part set down weeks later and thousands of miles away in

Chartres cathedral, they generally raved about it. That recording

went on eventually to sanctification in Deutsche Grammophon’s

prestigious Originals series.

In the early 1960s Ernest Ansermet was clearly less concerned

with the fad for sonic blockbusting than with sheer, honest musicality.

Thus, while Fritz Reiner’s 1960 Chicago “Living Stereo”

version of Scheherazade was the audiophile’s choice,

those more focused purely on the music often held Ansermet’s

Suisse Romande recording from a year later to be its superior.

That contrast is exactly paralleled in the case of the Organ

Symphony. Ansermet’s version was certainly well recorded

in good, clear stereo sound - even if it was not the finest of

which Decca engineers were then capable. For that listen to the

remarkable Ataulfo Argenta/London Symphony Orchestra album España,

still sounding absolutely stunning today after 52 years. But in

no way is the Ansermet a blockbuster. Instead it can be appreciated

as well thought out, intensely musical and an account to make

one look at the symphony once again with fresh eyes; perhaps even

to take it a little more seriously than usual. Superficial excitement

is not in evidence at all: indeed, at just 37:17 Ansermet’s

careful, rather stately interpretation comes in slower than any

other recording on my shelves: Martinon from 1975 is next at 36:15;

the same conductor’s 1966 recording clocks in at 35:19;

Toscanini’s 1952 version is, perhaps surprisingly, not

the quickest at 34:45; Munch in 1959 completed his classic account

in just 34:30. The fleetest recording comes from Barenboim in

Chicago and Chartres in 1976.

This repertoire was right up Ansermet’s street and his Swiss

orchestra clearly feels quite at home too. I especially enjoyed

the witty, playful account of Danse macabre: it may just

be in mono sound but for musicality it knocks the spots off yet

another “sonic blockbuster” of that era: a Decca Phase

4 version under, I think, Stanley Black that was, forty years

ago, the first Saint-Saëns that I had ever heard. Chabrier’s

España faces stiffer competition, however, for,

confronted with the combination of a superb performance and

fabulous sound, I’d go for Argenta over Ansermet any

day.

While a perfectly worthwhile and enjoyable release - and one that

certainly adds to our appreciation of Ansermet the consummate

musician - this is not one likely to displace other recordings

of this repertoire. It may seem a sadly superficial judgement

but, in the Organ Symphony in particular, sheer sound quality

does make a difference. It means, for example, that Toscanini’s

recording is one of the few in his complete 71-CD RCA Collection

that I do not listen to for pleasure. Ansermet’s version

is clear and sharp but its comparative restraint and that missing

special “oomph” mean that we are less than likely

to hear it on the hi-fi salesman’s playlist.

Rob Maynard

|

|