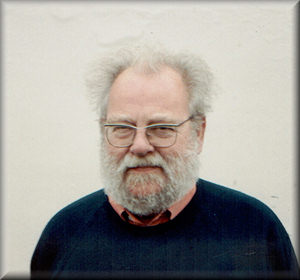

The Life and Works of Geoffrey

Winters.

Introduction.

In

his recently published memoirs Geoffrey Winters recalls that

a few years after his studies at the Royal Academy of Music

in the 1940s he met Sir Arthur Bliss at a Composers’ Guild luncheon.

He says of this meeting,

In

his recently published memoirs Geoffrey Winters recalls that

a few years after his studies at the Royal Academy of Music

in the 1940s he met Sir Arthur Bliss at a Composers’ Guild luncheon.

He says of this meeting,

‘I mentioned that he had been instrumental

in my becoming a composer. He replied, Did I want to thank him,

or sue him! ‘ (1)

To the young aspiring composer, Bliss’s levity

might have been distinctly off-putting. In retrospect, perhaps

it also serves to remind one of the exigencies of the compositional

process and the subsequent difficulties contemporary composers

may often experience in getting their works repeatedly performed

and widely recognised.

The celebration of Geoffrey Winters’ birthday

in October 2008 was a timely reminder of the need for a reappraisal

of his compositional output. Such a landmark event provides

an ideal opportunity to reflect and offer an overview of a lifetime’s

work which has been both prolific and profound. The development

of Winters’ work over the last six decades has undoubtedly established

him as a composer of considerable significance. Yet, his name

and reputation may be more familiar to music educationalists

and teachers, rather than to the concert-going public.2

It cannot have escaped those who attended the

world premiere of Winters’ Variations for Two Pianos Op.

19, performed by Claire and Antoinette Cann in the West Road

Concert Hall, Cambridge on 2 October 2008, that here is music

that is challenging, finely crafted and immensely rewarding.

With such an enthusiastic and rapturous reception the composer

received on this occasion, one feels that here is music that

should - and does - have an enduring appeal. The fact that the

work was composed nearly fifty years ago does however raise

questions as to why Winters’ work in general has not received

more exposure and prominence. Perhaps his propensity for too

readily assigning his music to the drawer when a performer or

publisher had rejected it, showed a lack of confidence in his

own work. This also showed in his reluctance to use the phone.

He used to refer to his wife, until she died three years ago,

as his ‘telephone secretary’. He is a little better now.

Winters’ main body of work encompasses instrumental,

chamber music, vocal and choral music through to large-scale

orchestral works such as his Violin Concerto Op. 51 and Symphonies

Opp. 23 and 55. From the gravitas of the opening movement of

the Concerto to the witty humour of the second movement of the

Second Symphony, the listener is treated to a range of music

of breath-taking contrast, ingenuity and expressivity. Smaller-scale

works such as the viola sonatas, works for recorders or solo

instrumental pieces, such as Domenico’s Music Box for

Harpsichord Op. 64, are no less impressive and make an important

contribution to the 20th century repertoire for these

instruments. One must also pay tribute to the extensive range

of works composed and published especially for children such

as The Year Op. 26 or Thames Journey Op. 31, both

written for junior voices and ensemble. Originating from the

late 1960s, these and other works for children were very successful

indeed.

Early Years

Winters was born in Chingford on 17 October 1928

and was the youngest of three boys. His father was a monumental

sculptor and this undoubtedly has influenced Winters’ life-long

interest and proficiency in calligraphy. Apart from his being

briefly apprenticed to his father at the age of 17 to gain a

skill in letter cutting and stone sculpture, he was brought

up to revere Eric Gill, Epstein, Morris and the calligrapher,

Edward Johnson. Indeed this influence is manifest when examining

any of Winters’ manuscripts, revealing a precision, attention

to detail and aesthetic awareness that is quite unique. Although

his mother was, by all accounts, a very capable pianist and

would sing ballads and music hall songs, Winters’ early musical

education at school was variable. Piano lessons commenced at

the age of nine, but progress was interrupted because of the

wartime evacuation. However, he did take an active interest

in composition. His first piece, which he still has in his possession,

was a funeral march, ‘...much inspired by my first piano

book of Mrs Curwen’s. What a strange thing to have in a book

for beginners?'(3)

In 1939 Winters passed his scholarship for Chingford

County High School, but on 3 September was evacuated to a billet

near Rochford. Over the next three years he moved to no less

than six billets countrywide and recounts that it was initially

one of ‘.... the unhappier periods in my life.’(3a) In

1940 he eventually ended up in the Forest of Dean and attended

the Parish Hall near Coleford for his school lessons. The French

teacher, Miss Boagey, made a lasting impression on him. It was

here that he heard her practising the Grieg Sonata in E minor,

Op. 7. As he says,‘I fell in love with the piece, which had

a lasting influence on me.’(4)

It was in his final billet that Winters found

happiness and contentment. Referring to his hosts as Uncle Les

and Auntie May he recalls, ‘Auntie May had been a piano teacher,

but when she married, Uncle Les (very autocratically),had forbidden

her to teach, or it seemed, to have anything to do with music.

This was the start of my career in music, for although she didn’t

practice, she had many standard classics. I was not very advanced

from my pre-war lessons, but I battled away with such works

as The Pathetic Sonata of Beethoven.....’(5)

Returning to Chingford in the summer of 1942,

Winters resumed his piano studies and excelled at theory. Taking

his school certificate in nine subjects he gained Matriculation

exemption. With ensuing A level studies Winters became passionate

about architecture. His musical tastes and experiences broadened

to Bliss, John Ireland, Vaughan Williams as well as Beethoven,

Mozart and Schubert.

Student Days and National Service.

Towards the end of the war, whilst attending

a Wigmore Hall concert, Winters introduced himself to John Ireland.

Ireland agreed to give Winters several tutorials as part of

his preparation for the Royal Academy of Music in 1945. Ireland

also wrote a letter to the Academy suggesting that Winters should

be taught by Alan Bush, a former pupil of his.

Also at this time, a chance meeting with the

Academy professor Frederic Jackson resulted in Winters giving

up sixth form and having piano tuition from Frederica Hartnoll

for the summer term. Winters acknowledges that in these three

or four months he improved his piano playing more than at any

other time in his life.

A successful audition at the Academy resulted

in Winters initially being tutored by Felix Swinstead for piano

and Priaulx Rainier for composition. At this particular time

both Frederic Jackson and Alan Bush were in the forces. The

adventurous attitude of Rainier broadened Winters’ musical horizons

in a variety of ways and he recalls being encouraged to attend

a Bartók quartet series at the Wigmore Hall. This experience

resulted in Bartók remaining a seminal influence on his style,

particularly in later years.

In his first spell at the Academy he also read

Hindemith’s ‘The Craft of Composition‘ and this was a formative

influence on his early compositional development. Winters very

much felt at this time that such an approach might be a solution

to him being a tonal composer, whilst allowing him to explore

and expand his chordal and harmonic repertoire.

Perhaps the central influence on Winters was

the systematic teaching of Alan Bush. Winters acknowledges that

this had a considerable effect on his craft and technique. Bush

encouraged close study of Bach Chorales and was insistent that

his students handled contrapuntal elements capably.

Emphasis on compositional structure was central

to Bush’s teaching, as was the expounding of the thematic system.

He was particularly keen on the derivation and development of

a work’s material from the opening thematic motif; something

which preoccupies Winters in a number of his works and most

notably in his Second Symphony.

Whilst at the Academy, Winters met Christine

Ive and their friendship blossomed into a proposal of marriage

shortly after Easter 1947. It was at this stage that Winters

composed 24 Preludes for Piano, dedicated to his future wife

and a setting of The Ancient Mariner for narrator, chorus

and small orchestra. That Summer, Christine successfully took

the LRAM in performance and Winters the intermediate B.Mus.

Call up into the army resulted in their marriage taking place

during a spell of compassionate leave. After National Service,

now with a young family, Winters resumed studies at the Academy

in 1949. At this juncture Winters started to give his works

opus numbers: A Wind Quartet, Op. 1 played at the Academy, the

Yorkshire Suite, Op. 2, all but in name a symphony and

the Toccata, Op. 3 for piano. These early works reveal Winters’

fluent and self-assured compositional technique in three very

different mediums.

With the Wind Quartet there is adventurous melodic

and harmonic invention containing many of Winters’ hallmarks:

a rising minor 3rd motif permeating much of the development

of material in the second movement, extensive textural contrasts

with bold unison writing and contrapuntal interplay between

the parts and extensive use of rhythmic devices such as syncopation.

The three movement Yorkshire Suite is

a substantial work with a distinctly programmatic theme. Winters’

close affinity with the Yorkshire Ridings gave him the inspiration

for the piece. Broadcast and recorded by the BBC Northern Orchestra

under George Hurst, the first movement, East Riding is

an evocative and atmospheric piece, in part reminding one of

the more pastoral influences of Vaughan Williams and early Tippett.

With the incorporation of the chimes of Beverley Minster, it

clearly demonstrates Winters’ adept and confident handling of

orchestral forces. Imaginative instrumentation is explored to

great effect throughout the whole work. Textural and structural

elements are skilfully handled, whilst the virtuosic and vibrant

orchestral passage work of the final movement merits repeated

listening.

From its opening bars, the Toccata for

Piano is a kaleidoscope of three note arpeggi in ever-changing

keys: C major, Eb major, F major, Db major, but nevertheless

remains strongly tonal. The exploration and ambiguous quality

of the harmonic material of the flowing opening passage is contrasted

with the more disjunctive and texturally transparent material

of the middle section. The rapidity and delicacy explored in

the writing, so impressively realised in an early recorded performance

by the composer’s wife, returns in the final pages. This is

made all the more surprising by the coda, which briefly returns

to the material of the middle section before finding a resolution

on three descending Cs. (6)

Winter’s gained his teacher’s LRAM in 1950 and

had joined the Graduate of the Royal Schools of Music course

at the Academy with a view to being able to teach in schools.

Although composing rather less at this time, he won a light

music prize with An English Jig Op. 6a and later a duet

version Op. 6b played by his wife and Margaret Kitchen as part

of an Alan Bush programme.

Gaining the GRSM in July 1952, Winters commenced

teaching music in Larkswood School, Chingford and was a strong

advocate of singing and the Tonic Sol Fa method. (7)

At this time Winters embarked on composing a

Thames Symphony, but all that came of it was a single

movement which became A River Pastoral (Intermezzo)

Op. 7.First performed by the Halle Orchestra under Maurice Handford

in a public rehearsal, A River Pastoral was subsequently

broadcast by the Berlin Radio Orchestra conducted by Alan Bush.

It remains one of Winters’ favourite works. The richly orchestrated,

elegiac and lyrical sound canvas is instantly memorable for

its opening rising motif, predominantly constructed around intervals

of a 4th, which become integral to the whole movement.

With this piece, and the romantic Viola Sonata, Op. 8 (one of

number of works written for the instrument and which won the

Harry Danks Prize), the powerful and at times bitonal Essay

for Orchestra, Op. 9 (also given a public performance by

the Hallé) and the somewhat more dissonant First String Quartet,

Op. 10 (which won The Clements Memorial Prize). Winters’ compositional

method and style briefly started to move towards a totally new

and unexpected direction.

Winters immersed himself in the 12-tone system

and this resulted in some serial compositions, most notably

the Three Inventions for Horn and Tuba, Op. 11, the Piano

Sonata Op. 12 and the Three Pieces for Clarinet and Piano

Op. 13. However, by his own admission Winters felt that the

esoteric, perhaps cerebral nature of the musical language and

style would not endear itself to the general public. After a

break in creative work, he became less preoccupied with serial

music and composed a Miniature Suite for Recorders Op.

17 and the Concertino for Piano, Horn and Strings Op. 18. Both

these works proved to be far more popular and accessible.

With the Variations for Two Pianos,

Op. 19 that followed, here was a work that embraced a more neo-classical

approach. Using as its main theme Friedrich Kuhlau’s Allegro

burlesco from the Sonatina in A minor, Op. 88, No. 3, the

seven variations that follow explore dissonance, structural

symmetry, textural clarity, extensive use and development of

the theme’s opening 3-note motif (Variation 1) and octave passages

(Variation 6) reminiscent of Prokofiev. Here Winters’ musical

language is decidedly more dissonant but within a tonal landscape.

Such other works as his Sonatina for Flute and Piano, Op. 28

and the Sonatina for Piano Op. 29, also have a neo-classical

influence. Winters also acknowledges the considerable influences

of Prokofiev and Shostakovich on his own musical language. It

is certainly the case that Winters’ knowledge and regard for

the past is in no way inhibiting and has provided a rich stimulus

for his creative imagination.

Middle Period Works

Spanning a 16 year span in the middle period of Winters’ composing

output, the Symphony No. 1, Op. 23 and the Symphony No. 2 Op.

55 establish a significant development and maturity in musical

form and language. What becomes increasingly evident over this

period is Winters’ eclectic and intellectual rigour. Here there

is a move away from the early influences to a more individual

and original musical language. This is quite apparent in the

harmonic and rhythmic contrast in the First Symphony which received

its first performances in London in 1973, including a performance

at the Royal Festival Hall by the then New Philharmonia Orchestra

under Owain Arwel Hughes. The success of this work lies in his

use of bold and colourful orchestral timbre and textural ingenuity,

a rich and varied harmonic palette and an organic growth within

the context of a taut and concise symphonic structure. Despite

Alan Bush’s comment that perhaps the work was not rhetorical

enough - its total duration is 16 minutes -Winters notes that

he was particularly interested in brevity at that time. The

Daily Telegraph critic wrote, ‘..the adagio’s spare and yet

thoughtfully written lines show what Mr Winters can do. For

a slow movement to reveal unsuspected weightiness is bit like

Shostakovich and so was this symphony’s finale with the brass

provocatively repeated A major chords pitted against a soaring

C minor/major melody......the work left no doubt that here is

a composer.’(8)

The Second Symphony, first performed by the Guildhall

School of Music Graduate Orchestra in 1978, is a more extensive

and expansive work with imaginative scoring particularly for

the percussion section in the jocular and jazzy second movement.

With the opening of the 1st movement being introduced

with a long sustained B emerging from the lower strings and

passed around to the rest of the string section, the sense and

feeling of timelessness conjures up a sound-world not that dissimilar

to the opening bars of Mahler’s 1st Symphony. As

Winters goes on to mention in the programme notes, the timeless

B... ‘.... collects on an A when the oboe joins in and in

a leisurely fashion this pair of notes is discussed and trilled

until the horns introduce the note C followed almost immediately

by Eb on the xylophone and piano. After a brief cello cadenza

C sharp is solemnly played by the brass. From these five notes

the remainder of the work derives its main melodic material.’(9)

The 2nd movement, introduced on five

approximate pitches for percussion instruments, also explores

additive rhythms and more unusual timbres such as key tapping

on woodwind instruments. The sombre opening of the slow third

movement contains hushed string cluster chords, subsequent use

of aleatoric techniques and incorporates most effective writing

for solo cello and violas. With the final movement there is

a reworking and recapitulation of earlier material particularly

in the final thrilling Piu Mosso section.

Set within the context of the 20thcentury

British symphonic tradition, that includes Vaughan Williams,

Walton, Tippett, Arnold and Rubbra to name but a few, Winters’

works make an important contribution to the genre. Along with

the Violin Concerto, they represent the pinnacle of his orchestral

output.

Over this period in time Winters taught music

in a secondary school and later as a college lecturer up until

his retirement in the late 1970s. Preoccupation with teaching

in a secondary school resulted in him composing very little

at this time. However, from 1967 came a series of works for

children which were readily published. On moving to Gipsy Hill

College as a lecturer he became prolific again and most notably

composed Reflections for Recorder Op. 45 and Conversations

for Recorder Consort, Op. 46.

Later Works

After the Second Symphony, Winters’ composed

an astonishing variety of works spanning 14 years. Now living

in Suffolk as a freelance composer he received numerous commissions,

including, Caprice: Brass Fair for brass band,

Op. 63, performed at the Brass Band Championships in 1983 and

Studies from a Rainbow for piano, Op. 70, performed in

Cambridge, the Purcell Room and most successfully in the States.

One of the outstanding works of this period is

Winters’ Meeting Point song-cycle, Op. 59, first performed

in the Wigmore Hall in 1978. The cycle of five songs, which

in a sense is autobiographical, sets the poems by Marlowe, Robert

Graves and Louis MacNiece in a contemplative and sentient manner.

With this and such later works as the exquisite Tributaries

for solo harp, Op. 79, the light-hearted Mutations for

two trumpets (1988) and Summer Songs for chorus, Op.

90, Winters continued to explore new directions in adventurous

and versatile ways. As with his compositional output as a whole,

one cannot deny that here is music that is more than deserving

of a wider exposure and recognition in the concert hall, through

radio broadcast and recording. Although many early recordings

exist of Winters’ works and a number of scores are still available

from the composer or his publishers, a reappraisal of much of

his repertoire is now long overdue. The upsurge of interest

in lesser known 20th century British composers, by

such enterprising recording companies as Naxos (and indeed from

other independent recording companies) in recent years, sets

a strong precedent for the work of Geoffrey Winters now to be

considered.

Notes.

1. Geoffrey Winters Memoirs: A Life of Loves, Lavenham Press 2008

2. Winters wrote many very successful music books for use in primary

and secondary schools over 25 years, published by Longmans Books.

Many of these books became integral to class music teaching and

essential coursework texts for teachers at a time when the National

Curriculum did not exist. Such titles as 'Sounds and Music, Books

1-3' aimed at 11-14 year olds and 'Listen, Compose, Perform',

the first coursework book for the new GCSE Music examination in

the mid-1980s, gave teachers and pupils a structured and progressive

approach that paved the way for a more coherent music curriculum.

3. Geoffrey Winters Memoirs: A Life of Loves, Lavenham Press 2008

3a Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. The recording of the Toccata was originally made onto aluminium

disc at 78rpm in 1952 and subsequently transferred to CD recently.

7. 'I was a strong advocate of singing and in addition sight singing.

I employed the rather unfashionable Curwen Tonic Sol Fa method

along with its associated hand signs. I always related it to staff

notation........ Later when recorders were introduced and then

Orferry (emphasis on ostinati and tuned percussion),I widened

my approach, but never gave up the voice as the main expressive

element of music, given to, almost, everyone.'

Geoffrey Winters Memoirs; A Life of Loves, Lavenham Press 2008

8. Sleeve note to CD private recording of Symphony No 1.

9. Sleeve note to CD private recording of Symphony No 2.

SELECTIVE WORK LIST

ORCHESTRAL

A Yorkshire Suite Op. 2 (1949)

A River Pastoral Op. 7 (1954)

Symphony No. 1 Op. 23 (1961)

Pageant for Orchestra Op. 37 (1969)

Action, Reaction, Interaction Op. 38 (1969)

Celebration for Orchestra Op. 50 (!974)

Concerto for Violin Op. 51 (1974)

The Mind of Man for chorus and orchestra. Op. 52 (1975)

Symphony No. 2 Op. 55 (1977)

Elegy for a Countryside for Horn (viola) and strings Op.

75 (1982)

The Forest: Tomorrow? Op. 84 (1986)

CHAMBER

Wind Quartet Op. 1 (1949)

String Quartet No. 1 Op. 10 (1956)

String Quartet No. 2 Op. 21 (1960)

Aspects for flute, clarinet,

horn and harp. Op.

24 (1961)

Conversations for Recorder Consort. Op. 46 (1971)

Contrasts on a Theme of Liszt for wind quintet. Op. 54

(1976)

Five Epigrams for String Quartet. Op. 62 (1978)

Again the Grass Grows Green for flute, double bass

and piano. Op. 78 (1983)

Serenade for flute, violin, harpsichord and cello. Op.

82 (1986)

Mutations for two trumpets. (1988)

INSTRUMENTAL.

Preludes for Piano. (1947)

Sonata No. 1 for Viola and Piano. Op. 8 (1955)

Three Pieces for Clarinet and Piano. Op. 13 (1957)

Variations for two pianos. Op. 19 (1960)

Sonatina for flute and piano. Op. 28 (1965)

Sonatina for Piano. Op. 29 (1966)

Reflections for Recorder. Op. 45 (1971)

Sonata No. 2 for Viola and Piano. Op. 57 (1978)

Domenico’s Music Box for Harpsichord. Op. 64 (1980)

Studies from a Rainbow for Piano. Op. 71 (1981)

Tributaries for solo harp. Op. 79 (1983)

Sky Dance for solo flute. Op. 88 (1988)

VOCAL

Two Joyce Songs for high voice. Op. 33 (1966)

Three Herricks songs for voice and guitar. Op. 41 (1970)

Phoebus Arise for soprano and ensemble. Op. 56 (1978)

Meeting Point song cycle. Op. 59 (1978)

Summer Songs for chorus and piano. Op. 90 (1990)

BRASS BAND.

Caprice: Brass Fair. Op. 63 (1978)

A Walkabout Waltz. Op. 72 (1981)

MUSIC FOR YOUNG PEOPLE.

Suite of numbers for recorders and glockenspiels. Op. 25

(1961)

The Year for junior voices and ensemble. Op. 26 (1962)

Sing It and Ring It for junior voices and ensemble. Op.

30 (1967)

Thames Journey for junior voices and ensemble. Op. 31 (1967)

Chanticleer for junior voices and ensemble. Op. 34 (1968)

A Cowboy Suite for junior ensemble. Op. 39 (1969)

Moonshine, a smugglers tale. Op. 61 (1978)

- Indicates, manuscripts,

sketches and correspondence lodged at British Library.

Contact point/address for scores and performing materials:

Geoffrey Winters,

4, The Causeway,

Boxford,

Sudbury,

Suffolk CO10 5JR.

TEL: 01787 211261

Article written by:

Martin Entwistle,

The Old Barn,

Crafthole,

Cornwall PL11 3BQ.

Tel: 01503 230707.

martinentwistle@hotmail.com