The link between

J.S. Bach’s sonatas and partitas

and Belgian violinist and composer

Eugéne Ysaÿe’s op. 27

is a strong feature of these works.

Direct quotations, such as the reference

to Bach’s second sonata in the Sonata

No.2 are the clearest pointers,

but the symbolism and formal relationships

pointed out and illustrated in Henning

Kraggrud’s own comprehensive booklet

notes leach through just about every

aspect of these works. The Bach

informs and strengthens the individual

qualities of each sonata, while

in no way turning any of them into

lame pastiche. Each of Ysaÿe's

solo sonatas is dedicated to a younger

violinist, those among the outstanding

players of their day. Not only do

they bear dedications to Szigeti,

Thibaud, Enescu, Kreisler, Crickboom

and Quiroga, they also contain numerous

more or less hidden messages for

these interpreters.

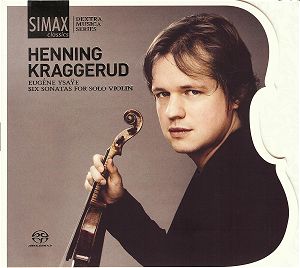

Henning Kraggerud’s

playing is sturdy and robust, and

where in live performances I have

heard some players over-romanticising

the more gentle movements, the Amabile

in the Sonata No.1 or

the Malinconia in the Sonata

No.2 for instance, Kraggerud

allows the music to speak directly,

giving it plenty of tenderness but

never slackening in intensity or

rhythmic direction. His technical

assurance is second to none, and

the most demanding passages are

breathtaking. I won’t say he makes

them sound easy – the sheer physical

requirements come over like hard-won

battles. Kraggerud always wins however,

giving enough detailed care to allow

the music to shine through, and

showing enough bravura to make the

most important dramatic moments

sound as if the world’s axis is

turning around the hairs of his

bow. The effects and colours in

Les Furies from the Sonata

No.2 crackle and spark with

all the sense of danger you get

from an overhead power cable. Kraggerud

brings out the ‘character’ nature

of the pieces as much as possible,

but it takes an educated ear to

spot many of the clues. Some of

the more apparent of these are to

be found in the ‘Kreisler’-orientated

Sonata No.4, in which his

technical style and bravado appear

interwoven through numerous fantastic

moments. The white-heat of

inspiration which saw Ysaÿe

create these works in a short period

during his 66th year

is reflected in Kraggerud’s performance

with utter conviction from beginning

to end.

This SACD hybrid

recording is truly excellent. In

stereo there is a little of what

sounds like channel-hopping now

and again, but when full surround

mode is used you have more of a

3D sense of the violinist moving

around. This must always be a bit

of a nightmare for sound engineers,

especially when editing, but the

production on this disc is superlatively

good. The violin played by Kraggerud

is a 1744 Guarneri, made in the

last year of the master’s life,

and showing the maker having to

resort to local materials. The back

for instance is made from beechwood

as opposed to the more exotic and

commonly used imported maple. The

loan of the instrument and recording

was funded by Dextra Musica, a series

of such recordings of which this

is a part. There are some lovely

close-up photos of the violin throughout

the well designed disc gatefold

and booklet for this release.

There are a number

of recordings of these remarkable

works around now, and the high technical

demands of the music mean there

are very few if any that one could

call weak. Of the complete sets,

Thomas Zehetmair on ECM has to be

one of the top considerations. Then

there is Leonidas Kavakos on Bis

and Frank Peter Zimmermann on EMI

– also both strong contenders in

the market. These performances all

seem to engender a strong following

in those with whom they have come

into contact, and there is no right

or wrong in this. Henning Kraggerud’s

excellent performances with their

value-added SACD recording can be

considered alongside all comers

as one of the very best at the highest

level.

Dominy Clements