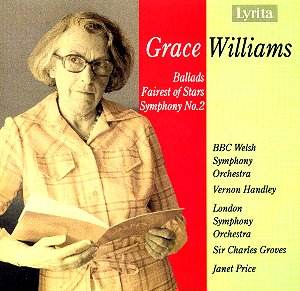

The Welsh composer

Grace Williams has been unfairly neglected

by concert promoters and record producers

alike. A pupil of both Vaughan Williams

and Egon Wellesz - and very nearly assistant

to Britten, declining his invitation

- she returned to her native town of

Barry, near Cardiff, after the Second

World War. It was there that she spent

the rest of her life, composing mainly

by commission from the National Eisteddfod

and Llandaff and Swansea festivals.

It is perhaps by placing herself out

of the British metropolitan musical

mainstream that Williams’ work has so

often been sidelined. On the strength

of the music on this disc - from BBC

and EMI originals - it is time for serious

reappraisal.

The earliest of the

three works, the Second Symphony

(1956, rev.1975), is also the most ambitious.

The first movement, Allegro marciale,

immediately proclaims debts to other

symphonic composers. The persistent

side-drum, trumpet fanfares and unison

wind accompanied by pizzi-staccato strings

are highly characteristic of Shostakovich’s

symphonic output. Likewise the violent,

militaristic quality harks back to Vaughan

Williams’ Sixth Symphony, whilst

the macabre waltz-like sections (replete

with swooning solo violin) recall the

shadowy world of Mahler’s Seventh.

Yet if the elements are suggestive of

others, the binding together of the

different strands are Williams’ achievement.

After the opening, she soon reveals

a romantic streak all of her own, without

ever being sentimental. The rhythmic

tension that the composer generates

grips like a vice, subtly changing from

4/4 to 6/8 and frequently adopting cross-rhythms.

The development section is tautly constructed,

throwing principal ideas together into

a complex but always lucid texture.

Indeed, the trumpet fanfares from the

opening permeate not only this section

but the movement in its entirety.

The Andante sostenuto

that follows is rather more gentle,

but no less bleak in its outlook. The

stark opening has a plaintive oboe melody

set against drone strings. Constant

fluctuations between major and minor

reflect the chromatic melody lines which

rarely open out but instead tug one

way or the other. Most of the melodic

movement is built upon simple stepwise

ascent or descent. The movement is immensely

compelling all the same and the orchestration

clearly helps-a prominent timpani rhythm

and quiet tam-tam are menacingly present

throughout. Williams provides some respite

in the conclusion to this movement,

coming to rest firmly in the major.

The ensuing Allegro

scherzando, however, returns to

the violently grim nature of the first

movement. Scurrying rhythmic motives

and frequent metric shifts generate

a huge amount of excitement. A fleeting,

slower central section is still incredibly

dark, with ominous slitherings in the

clarinets and biting trumpet interjections.

The rhythmic vitality

of the third movement is offset by the

Largo that follows. The opening

of this movement sees Williams in obvious

late Romantic guise; in both sonority

and harmony this is reminiscent of the

Adagio of Mahler’s (then) incomplete

Tenth Symphony. The simultaneous

sounding of major and minor chords reflects

the struggle of tonalities that has

permeated the whole symphony. Later,

the side drum and trumpet motives from

the first movement return, leading to

waves of climactic - though still troubled

- lyricism, before a sudden, quick ending.

Ballads (1968)

is unmistakeably the work of the same

composer yet, freed from the conventions

of symphonic forms, Williams seemed

less inclined to display her influences.

Three of the four movements take a single

melody and repeat it within different

orchestral and textural contexts. The

melodies often take on an improvisational

quality and the accompaniments show

the same sense of imagination as in

the Symphony. This is an essentially

dramatic work, designed to reflect different

aspects of Welsh culture and history.

Whether or not it succeeds on such a

level is unclear; nevertheless, it is

still highly compelling.

Both of these works

are exceptionally well played by the

(then) BBC Welsh Symphony Orchestra

under that tireless advocate of obscure

British orchestral music, Vernon Handley.

The sound is acceptable, though the

Llandaff studio acoustic is rather dry

and airless, resulting in some congestion.

‘Big’ works such as these should ideally

sound more expansive.

No such concerns apply

to the 1973 (EMI) recording of Fairest

of Stars. The sound here is as opulent

and expansive as one could wish. Indeed,

the work itself - composed specially

for the recording - is an even finer

piece than the Symphony. A setting of

lines from Milton’s Paradise Lost,

this is a rhapsodic, ecstatic work that

is totally distinctive from those of

other composers. The soaring, melismatic

vocal line is extremely well delivered

by Janet Price. Her rapid, flickering

vibrato only adds to the sense of wonder

and barely contained excitement, and

she is sensitively partnered by Groves.

This is a work that demands to be heard

and, given its highly idiomatic vocal

writing, one that certainly deserves

to be performed more often.

This disc is certainly

an ear-opener. If the idiom appeals

then much satisfaction will be gained

from exploring this fascinating repertoire.

As the only available recordings, they

would be a first choice even if the

performances were poor. Fortunately

the disc is both very well performed

and more than adequately recorded.

Owen E. Walton

see also review

by Colin Clarke