The story of the Louisville

Orchestra in the 1950s and 1960s and its contribution to

the recording of less well-known music, to say nothing

of its record of commissioning new music, is a remarkable

one. The man behind it all was Charles P. Farnsley, who

was both Mayor of the city and also the president of the

orchestraís board. It was he who, in 1947, persuaded his

colleagues and the orchestraís music director, Robert Whitney

(1904-1986), that the orchestra should embark on a programme

of commissioning new works and performing a new piece at

every single concert. Even more daringly, this proposal

was adopted at a time when the orchestra was facing a major

financial crisis. Beginning with William Schumanís Judith,

premiŤred in 1950, the commissioning programme really got

going in earnest in 1954 and by 1959 the orchestra had

commissioned and performed no less than 116 new works from

101 composers, many of them American, of course. The recording

project, which went hand in hand with the concert programme,

lasted for much longer and eventually some 400 works had

been set down. Most of these were first recordings Ė and

in many cases they remain the only recordings the works

have received. Itís excellent news that under the aegis

of Santa Fe Music Group some of these Louisville recordings

are now to enjoy a new Ė some would say overdue - lease

of life on CD.

The Louisville story

is summarised in the fascinating liner note accompanying

this CD. More detail about the history of the Louisville

Orchestra, including this project, is to be found in the

book, Orpheus in the New World. The symphony orchestra

as an American cultural institution Ė its past, present

and future (New York, 1973) by Philip Hart, the biographer

of Fritz Reiner (pp. 192-211)*. As Hart points out, many

of the Louisville works were by conservative composers

and all too many of them have remained largely unperformed

since their original Louisville performances. Nonetheless,

this should not detract from the significance of the orchestraís

achievement, nor for oneís admiration for the vision of

Farnley and of Whitney, who occupied the orchestraís podium

between 1937 and 1967.

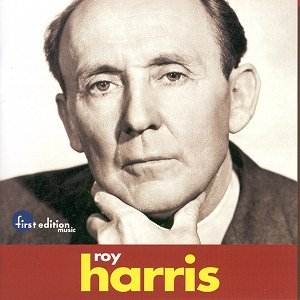

One of the major American

composers to benefit from the Louisville enterprise was

Roy Harris and of the three works featured on this CD one, Kentucky

Spring, was commissioned by the orchestra and premiŤred

by them. Both Kentucky Spring and the Violin Concerto

were also recorded by the orchestra for the first time.

So far as Iím aware none of the works featured here are

currently in the catalogue so their availability here is

doubly welcome.

The Fifth Symphony has

had other recordings. William Steinberg set it down with

the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, in a recording that

was not, I think, widely available commercially and there

was also a live performance by Kubelik and the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra available only from the CSO but that,

too, is long out of print. So for the moment this Robert

Whitney performance is the only one available. The work

was composed in 1942-3 (the documentation, confusingly,

gives both dates) and was revised in 1945, two years after

the premiŤre by Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony. Itís

a strong and rhetorical work and, to be brutally honest,

I think thereís more in the score than Whitney and his

players find. Their performance sounds rhythmically rather

foursquare and itís in this performance most of all that

one is reminded that, for all its endeavours the Louisville

Orchestra had its technical limitations. There are several

instances where the string attack is less than unanimous

and intonation is sometimes a bit suspect in the brass.

The recording doesnít help them, either, for the sound

is somewhat strident and confined, with little ambience

around the players. As it happened, around the time I was

listening to this disc I was also evaluating a CD of performances

recorded mainly in the 1950s in New York by Stokowski and

I have to say that the sound achieved by Stokiís engineers

was infinitely more flattering than the results we hear

on this 1965 recording.

But this performance

of Harrisís Fifth has much to commend it. The playing displays

lots of spirit and commitment, especially in the powerful

slow movement. I understand that Naxos has just announced

a complete cycle of Harrisís symphonies, which is great

news. No doubt when their recording of the Fifth appears

it will be in much better sound and the orchestral playing

will probably reflect the general advances in technique

that have taken place over the last four decades. However,

this Louisville recording will still deserve its place

of honour in the annals of Harris recordings.

The Violin Concerto is

also a substantial score. Composed in 1949, its first performance

was scheduled for that year and was to have been given

by the Cleveland Orchestra. Unfortunately, during rehearsals

all sorts of textual problems with the orchestral parts

came to light and the performance was cancelled. The score

then languished unplayed until 1984 when it was finally

heard for the first time. Then, as on this recording, the

soloist was Gregory Fulkerson, who gives a splendid account

of the solo part.

Itís a single movement

work though cast in four sections, each one of which is

helpfully tracked separately on the CD. The first section

is predominantly lyrical, in moderate tempo, and the solo

violin sings almost continually. The second section, which

is the longest, is more vigorous. Dancing rhythms predominate

but even here long lines are not completely banished. The

third section reverts to a slow speed; indeed this is a

heartfelt adagio, following which the final section is

almost a continuous accompanied cadenza. In this last section

there are some interesting episodes when the whole violin

section plays unison passages that almost sound like cadenzas.

Itís a fine work. It may not be in the same league as Samuel

Barberís Violin Concerto but itís well worth hearing and

scarcely deserves the neglect it has endured. The recorded

balance places the soloist very prominently in the aural

picture but both the recording and the performance give

a very good impression of the piece. Since another recording

must be considered a remote possibility Harris enthusiasts

should not hesitate.

The remaining work

is in much lighter vein. Kentucky Spring is

very much an outdoor piece. Itís a large scherzo, containing

a substantial lyrical central section. I found it to be

an engaging affair and Whitney and his players clearly

relish it. I canít resist quoting the composerís own summary

of the piece. ď[It] might be said to be a mixture of the

composerís memories and faith that he will again feel warm

sun in a blue sky and see a red bird in a green tree, to

say nothing of partaking of Kentuckyís most famous product.Ē

One canít overlook

completely the limitations in both the recorded sound and

in some of the orchestral playing on this CD. However,

it is still a very valuable and enjoyable release and Iím

extremely glad that these pioneering recordings are once

again available. I enjoyed this disc and I commend it warmly.

John Quinn

*

The book by Philip Hart, mentioned above is, sadly, long

out of print. It is a fascinating and detailed book, well

worth investigation by anyone interested in the subject.

It may be possible to acquire a second hand copy, as I

did a few years ago, from www.alibris.com

see also review

by Rob Barnett

BUY NOW

AmazonUK AmazonUS