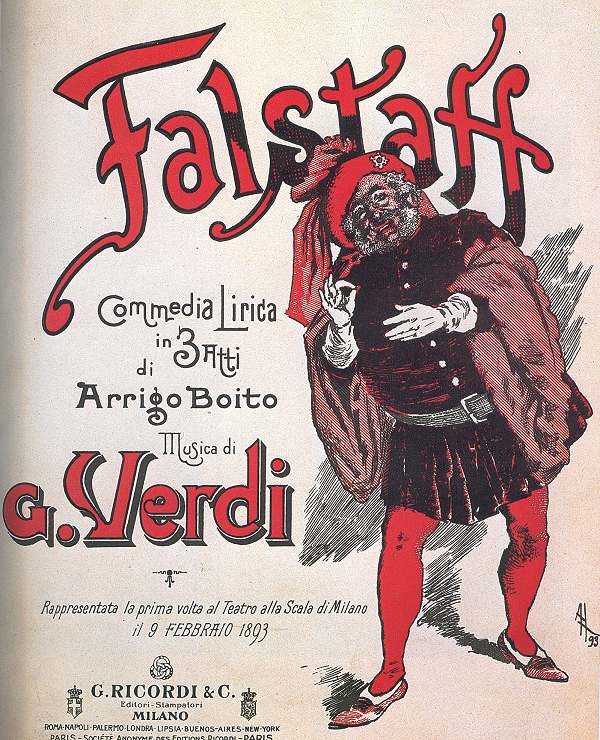

Falstaff was

the culmination of Verdi’s long career

as an opera composer. He had really

believed his compositional days were

over after Aida. Nearly a decade

later, persuaded by his publisher, he

embarked on a rewriting of Simon

Boccanegra. This involved his working

with Arrigo Boito, an accomplished librettist

and also a composer; it was an association

Verdi relished. Premiered at La Scala

in March 1881 the revised Boccanegra,

unlike the 1857 original, was a triumph.

Even at the age of 68 his inner genius

was alive and well. Ricordi and Boito

subtly pointed Verdi towards Shakespeare’s

Otello. Shakespeare was a poet

revered by Verdi. Gently, via synopsis

and Boito’s verses, Otello was

written. It was a piece with significant

orchestral complexity and marked a major

compositional movement from Verdi, even

compared to the greatness within Aida

and Don Carlos, its immediate

predecessors. As Budden (The Operas

of Verdi. Vol. 3) puts it, In

common with all great tragedies Otello

harrows but at the same time uplifts.

It was premiered, again at La Scala,

six years after the revised Boccanegra.

Verdi was then 74 years of age and really

did think he had finished operatic composition.

But he had not allowed for Boito. Three

years after the premiere of Otello

Verdi wrote to a friend What

can I tell you? I’ve wanted to write

a comic opera for forty years, and I’ve

known ‘The Merry Wives of Windsor’ for

fifty… however, the usual buts and I

don’t know if I will ever finish it…I

am enjoying myself. Boito’s vital

contribution in enabling Verdi to match

Shakespeare was in his capacity for

drawing out a taut libretto from the

plays concerned. Boito reduced Otello

by six-sevenths and in Falstaff

reduces the 23 characters in The

Merry Wives of Windsor to just ten

in the opera. The composer wrote Falstaff

for his own enjoyment whilst his

mind must, inevitably, have gone back

from time to time to his only other

comic opera, Il Giorno di Regno,

and its abject failure at its premiere

at La Scala in 1840. With Falstaff,

the outcome was all that Verdi could

have hoped. His ‘little enjoyment’ as

he called it was a triumph at its premiere

at La Scala on 9 February 1893. The

greatest Italian composer was 80 years

of age. It was a great culmination to

a great career.

Verdi’s orchestration

in Falstaff, with its final fugue,

represents challenges to even the best

of the conductors with a natural feel

for the Verdian melodic line and idiom.

None had this feel more than Arturo

Toscanini whose presence in the orchestra

of La Scala at the premiere of Verdi’s

penultimate opera, Otello, is

well documented. Many commentators,

who view them as definitive, constantly

refer to his series of live performances

of Verdi operas issued by RCA. That

of Falstaff in 1950 (74321 72372-2)

featured Giuseppe Valdengo in the name

part. Its issue blew the very worthwhile

1949 Cetra recording out of the water

in pro-Toscanini critics’ eyes. Featuring

the sappy and well-characterised Falstaff

of Taddei in an all-Italian cast under

Mario Rossi’s idiomatic, flexible and

sympathetic baton it did not have a

wide distribution. Its many virtues

can now be better assessed via the Warner

Fonit re-issue (8573 82652-2). To mount

a realistic challenge to the Toscanini

hegemony, producer Walter Legge sailed

in with a well-balanced cast for his

label. This is the issue under review.

It first saw the light of day in mono

in 1957. The sonics of the original

mono recording, made in London in that

most sympathetic venues, Kingsway Hall,

and with Christopher Parker in charge,

made an immediate impact. Rumours began

to circulate as to a stereo set-up having

been present at the recording sessions

and in 1961 a stereo version was issued.

Why the delay? I do not know if there

were technical reasons in respect of

pressing the then new groove patterns

in the LPs necessary for stereo. From

personal experience I do know that even

with first class stylus and arm, heavily

modulated passages could cause problems.

I had hassle at the time with the last

scene on a Decca stereo issue of highlights

of its Ballo in Maschera. Neither

retailers nor record company could resolve

the issue. On this recording Parker

does facilitate Karajan’s very wide

orchestral dynamic and which may have

posed pressing problems in the early

stereo days.

It was not only Karajan’s

variation of dynamic and the mellifluous

orchestral sound that was greatly admired

in this recording, but also his grasp

of the humour, comic drama and moments

of bitter irony. In this he was aided

by Tito Gobbi’s interpretation of the

title role. Although it was argued,

and after innumerable further recordings

of the work it still is, that Gobbi

does not have the ideal ripeness, fruity

sap if you like, for the role. Maybe,

but he lives and portrays the facets

of Falstaff’s character and every nuance

of the words as no other interpreter

has done since. Equally important, he

reacts to and plays off his colleagues

in a manner that is unequalled in any

other recorded performance. This is

vividly heard in his initial welcoming

of Mistress Quickly on her bringing

response to his letters to the wives

(CD1 tr.14) and his different tone and

characterisation when she returns, after

his experience of being tipped from

the laundry basket into the Thames,

and tempts Falstaff the Herne’s Oak

to (CD2. 13-14). Very evident also are

the subtle differences in Gobbi’s vocal

bravado in Falstaff’s honour monologue

(CD1 tr.4) and his singing as he calls

for wine after Falstaff’s dipping as

he praises his paunch and the lack of

honour such as his elsewhere. As characterisations

go, Gobbi’s Falstaff is matched in every

respect by Fedora Barbieri’s Quickly.

No question about vocal colour here,

her fruity contralto tones are as to

the manner born; an outstanding interpretation.

If none of the other singers quite come

up to the standards of Gobbi and Barbieri,

there is barely a weak link. Luigi Alva’s

Fenton is light-toned and beautifully

phrased. Anna Moffo, in one of her first

recordings, has an ethereal middle voice

that comes into its own in the final

scene (CD2 trs.17-26) although there

is a touch of unsteadiness at the very

top of her voice. Elisabeth Schwarzkopf

is a little arch as Mistress Ford whilst

Rolando Panerai as her husband is strong-voiced

in a role that suits him well (CD1 trs.14-20).

Nan Merriman is a good Meg whilst Renato

Ercolani and Nicola Zaccaria are excellent

as Falstaff’s two-faced cronies.

This recording was

excellently remastered in 1999 for issue

in EMI’s Great Recordings of the

Century series (7243 5 67083-2).

This bargain-priced version follows

the same disc and track layout. That

is my only criticism. Opportunity should

have been taken to put all of acts 1

and 2 on CD1. There is a track-listing

and the same essay and excellent track-related

synopsis as on the GROC issue which

has a full libretto and translations

lacking here. At bargain price this

excellent recording and performance

should join the shelves of any Verdi

collection from which it is currently

absent.

Robert J Farr

see also review

by Christopher Fifield