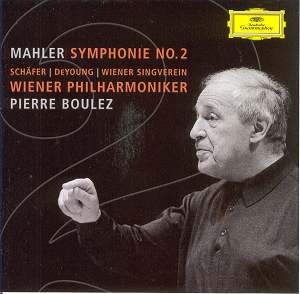

A Financial Times critic

said of this recording that it is a

"life-changing experience for anyone

who thought they knew their Mahler".

I hadnít read that until after Iíd listened

many times over, but he expresses exactly

what I feel, too. This performance really

does give a new perspective on a much-loved

symphony. It is especially important

because it has been over thirty years

since Boulez last recorded this symphony.

Whatever a conductor

of this stature has to say is going

to be worth listening to. Decades ago,

Boulez said, when speaking of Mahler,

that the world was "approaching

the end of an era surfeited with richness,

asphyxiated with plethora Ö Goodbye,

romanticism, with your fatty degeneration

of the heart!" Mahler was in so

many ways ahead of his time. As Boulez

continued Mahlerís music "had little

of the typical fin de siècle

turgidity Ö more relevant is the anxiety

of an artist creating a new world that

proliferates beyond his rational control,

a dizzying sense of uniting agreement

and contradiction in equal parts Ö and

the search for an order less obviously

established and less easily accepted".

Thus Boulez hears in Mahler a modernism

thatís bracingly refreshing. This is

a recording of startling insight, and

extremely valuable in terms of advancing

Mahler performance practice.

From the start, this

interpretation highlights the symphonyís

architecture. Indeed, this would be

an excellent first version for anyone

who doesnít know the symphony at all,

because the development is so lucid.

Even the most pianissimo details

can be heard clearly, yet the sense

of purpose is such that every sound

has a function, and makes a contribution

to the whole. Each theme is deftly delineated.

The great angular shapes of the Allegro

maestoso are there for a reason,

and have a role to play in the progress

towards the resounding culmination of

the "Resurrection" in the

final movement. A few years ago, Boulez

and the Vienna Philharmonic recorded

Mahlerís Third Symphony, where similar

great walls of sound push the music

towards an inexorable conclusion; here

we have even more powerful surges. For

Boulez, this "sense of trajectory"

is an integral part of the musical logic.

He makes the Second Symphony move with

remarkable vigour. Itís irrelevant what

the actual timing might be Ė what matters

is that it flows well and feels perfectly

judged.

Orchestral playing

on this level is inherently exciting.

Of course you know whatís happening

next, but you canít quite believe that

playing can be so good, so nuanced,

so exquisite. It does real justice to

Mahlerís music, where large forces must

be handled with precision and power,

yet, at the same time, be as refined

as if in chamber ensemble. Many times,

the playing is so achingly beautiful

you donít want the moment to end, and

yet it is not the virtuosity per

se youíre admiring but the way it

achieves the musical development as

a whole. While listening, I was stunned

to realize that Iíd been weeping real

tears at the sheer beauty of this level

of musicianship. Mahler was a conductor

who wanted very high standards, though

orchestras in his time were often not

as sophisticated as they are now. Perhaps

he, too, might have wept with joy listening

to how the Vienna Philharmonic brings

his notes to life with such feeling

and clarity.

In the second movement,

the orchestra sounds as if its virtuosity

is utterly effortless, so graceful is

its "nicht eilen". The first

movement may be more immediately striking,

but this orchestra and conductor show

that the quiet Andante, is no

less fascinating, for they define its

complex counter melodies and invention

with clarity. Later, the Fischpredigt

theme is played with outstanding vivacity.

Even without knowing the reference,

the playing evokes the image of vivid

agility. In the Scherzo, Mahler

expresses whirling movement, vibrancy,

constant upheaval, where, as he wrote,

"the world appears as in a concave

mirror, distorted and mad". Boulez

is vividly precise with the dissonances

and sudden swoops of tone. Yet even

in these dark moments, there are hints

of the triumphant theme to come. This

is an interpretation which elucidates

how brilliantly Mahler integrated his

ideas.

In this Urlicht,

the Röschen rot really

seems to emerge from deep roots. The

text is an overwhelmingly profound declaration

of faith, one that the composer was

to develop throughout his career. It

is a myth that this must be sung without

vibrato, for well modulated vibrato

breathes resonance and depth into long-held

vowels. DeYoung has sung a lot of Mahler,

and for good reason. Hers is a voice

with rich, natural dignity and she uses

it with a genuine understanding of the

ideas expressed. More surprisingly,

Christine Schäfer gives an exceptionally

beautiful performance, since her voice

is on the light side for Mahler. But

Schäfer and Boulez have worked

together so many times and seem to bring

out the best in each other.

This is one of the

most inspiring Auferstehíns Iíve

heard. I thought I knew it well, but

this really was a revelation. That first

fanfare could blast away cobwebs. Gradually

the "soaring" motif is introduced,

beautifully underscored by pizzicato

strings, whose music is echoed on horn.

Then, like a tsunami, a great drum-roll

announces the exposition of the main

theme, trumpets blazing, strings sweeping

in perfect formation. Here is where

clarity of concept pays off: Boulez

keeps the textures clearly defined,

keeping details in focus without losing

the dynamic. Each climax seems to give

way to ever-expanding new vistas. Imagine

them as you will, as walls of sound

and light, or mountain peaks, anything,

it doesnít matter as long as youíre

following the traverse, for that sense

of journey, of building and striving

is essential. It doesnít need to be

lumpen to be effective. Boulez carefully

unravels the perpetual motion in the

Scherzo, and builds up plateaux

of crescendi that lead, inexorably,

towards a final goal.

Almost reverentially,

as if approaching from a distance, the

chorus arises from the orchestra just

as the alto part had done earlier. This

reinforces the sense of trajectory that

has been the undercurrent throughout.

Then, you hear why Boulez keeps choosing

Schäfer. With the merest wash of

colour, she introduces a serene sense

of purity tinged with joy "...

hast nichst umsonnst gelebt, gelitten!".

She may not have as much to sing

as DeYoung, but what she does is critical,

for she embodies a new level of light

that encapsulates the whole idea of

resurrection. Literally, "mit

Flügeln, Öwerdí ich entschweben

zum Licht, zu dem kein Augí gedrungen!"

- "With wings, I shall soar upwards

to the Light, to which no eye has soared".

Boulezís interpretation

is truly infused with light, and illuminates

how Mahlerís music germinates and grows.

Mahler was a man of mental acuity, who

was uncommonly well informed and literate,

and who kept pursuing new ideas and

concepts. Even in his Romantic moods,

he was not given to sentimentality.

Boulez concentrates on how the music

works, and on what Mahler felt about

it. This is important, because Mahler

was a thinker and intellectual. In many

ways, his whole career was a search

for the meaning of life, developed through

the prism of music. Not for him, I suspect,

"the fatty degeneration of the

heart" that has crept into some

aspects of Mahler appreciation. This

recording will draw fire, as all good

and original work seems to do. But it

is an essential for anyone genuinely

interested in learning more about Mahler

and Mahler interpretation. Itís not

instantly flamboyant, but repays careful

and perceptive listening. The last words

in the symphony say it all: "was

du geschlagen, zu Gott wird es dich

tragen" (what thou hast fought

for shall lead you to God"). This

truly is inspirational.

Anne Ozorio