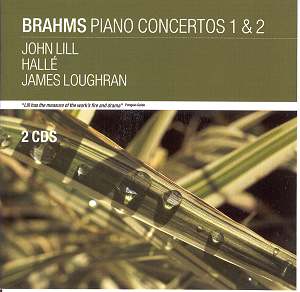

Oh dear, Resonance

are getting really good at Brahms cycles

which are very fine in parts and unrecommendable

in others Ė see my review

of the Liverpool/Janowski set of

the symphonies.

At the start of no.1

I thought the Hallé strings seemed

remarkably few, though no fewer than

those Brahmsís favourite Meiningen Orchestra.

The resulting clarity and forward wind

may sound more "authentic" today than

people thought when it was first issued.

Whatís more, I very much appreciated

Loughranís lean, muscular style, forwardly-moving

and classical. So many performances

today drag out this movement. There

is a slight slackening for the contrasting

material but without steering into the

doldrums. When Lill enters we can hear

that the approach is his as much as

the conductorís. He doesnít go in for

massive sonorities or barnstorming virtuosity,

but his textures are beautifully clean

while his excellent legato prevents

any suggestion of dryness. In its conversational

qualities, in its sense of moderation,

I thought this very close to Brahmsís

own language.

And so, too, with the

slow movement which, while grave, is

allowed to flow. The finale, at a fairly

moderate pace, has both purpose, character

and vitality.

Now I admit that some

listeners may find this unchallenging.

Iím prepared to defend it by saying

that performances that go all out for

drama, or massiveness, or heaven-storming,

or whatever, often lose out on other

things along the way. As a corrective

to exaggeration, I shall keep this by

me.

After the flowing tempi

of no.1 my first problem with the first

movement of no.2 was the very slow tempo.

As the horn started I thought this was

going to be one of those performances

that play this theme much slower than

the rest of the movement, as a sort

of motto-theme. But no, it is held pretty

steady right through. Joyce Hattoís

version raised a few eyebrows in this

respect (Lill is a few seconds longer

still) and both I and my colleague Jonathan

Woolf felt that it worked fine when

she was playing but created some problems

for the orchestra. Now I must say that,

with Loughran at the helm, thereís no

problem about the orchestra. Again he

essays a lean style with clean textures

and alert rhythms, while not ignoring

the more romantic parts. Lill, once

again, is clean and unsensational. At

first I quite liked it, but gradually

I felt it wasnít adding up. Given a

listless scherzo, in which the orchestra

sounds unengaged and less accurate than

usual, a wishy-washy slow movement and

a joyless finale, I am bound to ask,

why?

The point is, perhaps,

that the first concerto is an early

work. It impresses by its classical

rigour and single-mindedness, qualities

which Lill and Loughran grasp well.

The second is a late work, infinitely

more varied, more challenging in its

climaxes, more ardent in its long romantic

themes, but also bubbling with humour

and joi-de-vivre in its Hungarian

finale. Brahms has changed and developed,

but Lill and Loughran seem unaware of

it. In view of the excellent symphony

cycle by Loughran, Iím reluctant to

blame him too much, though. What passed

as rigorous and well-balanced in no.

1 makes no. 2 sound as if it were written

by Parry on an off-day. Itís certainly

one way of reminding yourself of what

a range of mood there is in this work,

to hear it played by someone who apparently

hasnít noticed, but youíd hardly want

to get the record just for that.

No, no.1 would get

a recommendation on its own but in tandem,

no way. If the famous Gilels/Jochum

performances are available - they havenít

often been out of the catalogue - youíll

get the op.116 pieces into the bargain.

And, if you donít mind old sound, thereís

a lot to be learnt from Schnabel on

Naxos.

Christopher Howell