Since I have some reservations to make,

I should like to start by saying that

I put this on without great enthusiasm,

supposing that primitive sound and old-fashioned

performance practices would make it

advisable to hear one act at a time.

Instead, I listened to the whole opera

without a break, and really enjoyed

it far more than the "authentic"

Naxos recording of the "pure"

French version which came my way recently

- review.

Here, then, is another

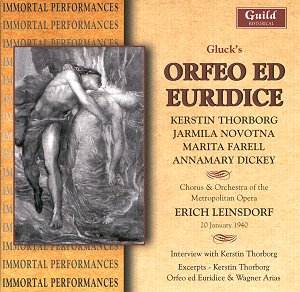

piece of Met history. Following Toscanini’s

performances with Louise Homer in 1914,

Orfeo ed Euridice was not heard

again there until 1938 when Bodanzky

revived it with Kerstin Thorborg. Further

performances followed in 1939. After

Bodanzky’s death that year the young

Erich Leinsdorf took over the German

repertoire at the Met and consequently

was at the helm for the present 1940

live broadcast. A year later the production

was repeated for four performances directed

by Bruno Walter, with whom Thorborg

had already sung the role in Vienna

and Salzburg. No Walter performance

has come down to us, so our knowledge

of Thorborg’s celebrated interpretation

depends on the 1940 revival under Leinsdorf.

It can be appreciated in sound which

is mostly firm and clear and is really

as good as we have a right to expect

for this sort of thing.

Bodanzky was a notable

cutter and adapter (he wrote his own

recitatives for Fidelio) and,

though Richard Caniell refers to Leinsdorf’s

version of the score I should have thought

it more likely that the young conductor

was simply briefed to play Bodanzky’s

score as it stood; certainly, the omission

of the overture and the foreshortening

of the first scene of Act Three sound

more like Bodanzky ideas than Leinsdorf

ones. When a conductor of Walter’s experience

arrived a year later it was another

matter and he opened out these cuts.

On the other hand,

there is no reason to doubt that the

shape of the music on this occasion

was Leinsdorf’s own. He takes a powerfully

tragic view from the outset, with slowish

tempi which are nevertheless propelled

forward inevitably by a purposeful rhythmic

tread. When he lets fly in the Dance

of the Furies the result is fearsome

indeed. Caniell is pretty rude about

this aspect of Leinsdorf’s treatment

of the score but I must say I found

it exciting. Here and in the Chaconne

the conductor’s clear textures and sizzling

articulation seem a blueprint for many

of today’s "authentic" performances

and, while an "original instruments"

conductor today would probably take

the Dance of the Blessed Spirits faster

(Ryan Brown certainly does on the Naxos

issue I mentioned above), the cool detailing

of Leinsdorf’s response nonetheless

seems closer to our own day than to

his. My reservation, and this is where

Leinsdorf still today divides opinion,

is that while I was certainly gripped,

my involvement remained intellectual

rather than emotional, presumably because

Leinsdorf’s own involvement was so.

No doubt Bruno Walter infused the work

with greater humanity, and if we can

only guess at the results, maybe the

audiences at La Scala heard something

along the same lines, Gluck’s classical

world illuminated by a romantic Claudian

glow, when Furtwängler conducted

the opera there in 1951, with Fedora

Barbieri and Hilde Gueden, a recording

of which has survived and was

recently reviewed for the site by

my colleague Jonathan Woolf.

Kerstin Thorborg was

the Orfeo of her generation,

only too briefly succeeded by the short-lived

Kathleen Ferrier. Her powerful, dark

voice carries chest resonances which

mean that at times she can almost seem

a male alto, while at others she takes

on a more feminine hue. It is a stately,

dignified interpretation with a notably

clearer enunciation of the words than

any of the other singers here provide

– though in comparison with a native

Italian like Barbieri she is perhaps

too careful, and her "Rs"

are decidedly Teutonic. Barbieri is

much more overtly passionate. While

Thorborg seems to fit admirably with

Leinsdorf’s interpretation, a suggestion

that she might have wished something

different comes with her 1933 recording

(in German) of the opera’s most famous

aria. Here the conductor allows a slower

tempo, about the same as the famous

Ferrier recording in English; Leinsdorf

is not as fast as Stiedry in Ferrier’s

Glyndebourne recording, a tempo which

Ferrier didn’t like at all, but he keeps

things moving pretty purposefully. With

this framework, Thorborg offers in 1933

a much more intimate, withdrawn and

obviously heartfelt reading. But the

sheer size of the Met, as well as the

conductor, may have contributed to her

more "public" manner in 1940.

The other parts in

this opera do not have a lot to do;

Novotna is an attractive Euridice, Marita

Farell a soubrettish Amore. Chorus and

orchestra are a good deal more precise

than they tended to be in Europe in

those days. The broadcast announcements

at the beginning and end of each act

have been preserved and the set is completed

by a quite long interview with Thorborg

and some Wagner extracts. The date of

the interview is not known, and nor

is the interviewer, though from the

sound of her voice and the reference

to a number of her colleagues in the

past tense it must have been post-1962

(Thorborg died in 1970). The Wagner

extracts show her wonderfully even voice,

rich and gleaming in every register,

her exemplary technical control and

her fine musicianship. They also suggest,

and the interview confirms, that she

may have been a most professional singer

and a considerate, hardworking colleague,

but perhaps not aflame with inspiration,

especially when inspiration is signally

lacking in Karl Riedel’s accompaniments.

With an inspiring presence on the rostrum

it was no doubt another story, and she

was by all accounts a striking presence

and a fine actor.

One or two aspects

of production call for comment. Firstly,

it was reprehensible indeed not to name

the conductors and orchestras of the

1933 Gluck and the Wagner extracts (I

have reinstated them after an Internet

search). Secondly, while Richard Caniell

refers to the considerable research

which took place to trace the version

of the score and libretto used, obviously

those concerned did not look at the

libretto which accompanies the Monteux

performance with Risë Stevens which,

though recorded in Rome, actually documents

the 1955 Met revival. Had they done

so, they would not have needed to label

CD1 track 6 lamely as "Ritornello"

when Thorborg can be heard to sing "Restar

vogl’io" with perfect clarity,

nor to call track 14 "Si les doux

accords de ta lyre" when Marita

Farell’s Italian, though poor, is not

so bad you could mistake it for

French, or doubt that she is singing

"Se il dolce suon de la tua lira",

nor to exchange "Vivr’Amore"

for "Divo Amore". Above all,

they need not have given up the ghost

at track 33, providing "E’ quest’asilo

ameno e grato" from another source,

when the words "Questo asilo di

placide calme" can be heard without

any difficulty. Textual variations between

the Leinsdorf and Monteux versions are

in fact minimal in the first two acts,

more substantial in the third; it would

appear that the Met was still using

the same material in 1955, plus Walter’s

reinstatements.

The origin of all this

confusion lies in the fact that, while

Jonathan Wearn and Professor Hugh MacDonald,

on behalf of Guild, have correctly taken

into account the three primary sources

– the Italian version (Vienna 1762),

the French version (Paris 1774) and

Berlioz’s conflation of the two (Paris

1859) – they seem not to have borne

in mind that most performances up to

the mid-20th Century used

neither of these but the so-called "Ricordi

version", or something like it,

which was basically the Berlioz version

back-translated into Italian. This was

necessary because Gluck added new music

for the French version, and revised

other parts, so Calzabigi’s Italian

libretto cannot e sung "straight"

to the French version. Track 33 is a

good example of this, since "E’

quest’asilo ameno e grato" is a

literal translation of the French "Cet

asile, aimable et tranquille",

which is in its turn a free rendering

of "Questo asilo di placide calme".

So a range of variants grew up which

basically accepted the Berlioz as their

musical text, but fiddled around with

the Italian words. Furtwängler’s

performance is musically more or less

the same as Leinsdorf’s (with the Overture

reinstated and some variations towards

the end), but often substitutes a different

sung text.

Lastly, Guild claim

that "Che farò senza Euridice?"

is sung by Euridice herself, an unlikely

state of affairs.

In spite of my comments,

if you don’t mind 1940 sound and want

an austerely tragic, but vital, view

of this opera, this issue is a good

deal more than a collector’s piece.

Christopher Howell

see also review

from Jonathan Woolf