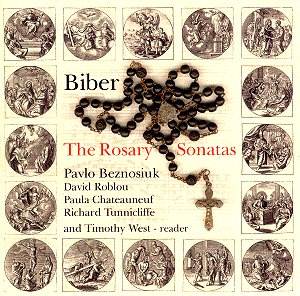

The 'Mystery Sonatas'

are among the most intriguing compositions

of the 17th century. Nowadays they are

certainly the most popular of Biber's

compositions, as the number of recordings

indicates. The catalogue already contained

a handful, and at the occasion of the

tercentenary of Biber's death, another

handful was added last year, two of

which are to be reviewed here.

The collection consists

of 15 sonatas for violin and basso continuo,

with an added Passacaglia for violin

solo. The title page of the manuscript

has disappeared. Therefore it is not

known what Biber called the collection.

Nowadays they are usually referred to

as 'Mystery Sonatas' or 'Rosary Sonatas'.

The reason is that in the manuscript

every sonata is preceded by an engraving

showing stages from the life of Jesus

and of his mother Mary. These can be

thematically linked to the mysteries

of the Rosary.

The collection is divided

into three groups of sonatas: the 'Joyful

Mysteries' (Sonatas I - V), the 'Sorrowful

Mysteries' (Sonatas VI - X) and the

'Glorious Mysteries' (Sonatas XI - XV).

As the engraving which precedes the

concluding Passacaglia shows, an angel

holding the hand of a child it is often

labelled 'the Guardian Angel'.

A particular feature

of this collection is the use of the

'scordatura' technique, meaning that

one or more of the strings are retuned

as indicated at the start of the sonata.

This can hardly come as a surprise:

although Biber wasn't the only composer

to use this technique, he prescribed

it more frequently than any other. With

the exception of the first Sonata and

the Passacaglia all sonatas require

retuning, resulting in 15 different

tunings throughout the collection.

There are a number

of questions regarding these works,

which still can't be answered with certainty.

One of these is when

and for which occasion they were written

and under what circumstances they were

performed. It is thought they were written

around 1678. They were dedicated to

Max Gandolph, the archbishop of Salzburg

and employer of Biber. From the dedication

text we learn that the archbishop strongly

promoted the worship of the Virgin Mary

and Rosary devotion in particular. The

fact that these sonatas were never published

has led to the assumption that they

were written to be performed - probably

by Biber himself - in Max Gandolph's

own chapel, during his meditation about

the mysteries of the Rosary. But others

suggest they could have been performed

in the Aula Academica, the lecture hall

of the Jesuit confraternity in Salzburg.

The hall contains fifteen paintings

depicting the mysteries, and the Jesuits

strongly advocated Rosary devotion via

music.

Another question relates

to a connection between the music and

the mysteries of the Rosary. There have

been attempts to present the sonatas

as depictions of events in the life

of Jesus and his mother. Some musical

figures can be interpreted as illustrations

of particular events as described in

the Rosary psalters of the time. However

that doesn't make these sonatas 'programme

music'. One has to assume that Biber

uses affective and rhetorical commonplaces

to stimulate meditation about the mysteries.

In this regard it is

appropriate to explain the term 'meditation'.

Nowadays music presented as 'meditative'

is mostly soft and unobtrusive, allowing

the listener to dream away and sink

down into himself. However the latin

verb 'meditare' also means 'study thoroughly'

or 'practice'. In the liner notes of

Pavlo Beznosiuk's recording James Clements

writes that "by contemplating the image,

reading the texts, and hearing the music,

individuals were supposed to create

a mental picture of the mystery, often

in minute detail and at great length".

And Wiebke Thormählen, in the booklet

of Sonnerie's recording, says: "Graphic

sound painting has parallels in much

counter-Reformation art which seeks

a powerful immediacy of visualisation

with the depicted emotions, but provoking

so strong a reaction that his emotions

are heartfelt rather than merely sympathetic".

This explains the often strongly dramatic

music to be found in this collection

which is disturbing rather than 'meditative'

in the modern sense of the word.

The recordings reviewed

here have their own idiosyncrasies.

In Pavlo Beznosiuk's recording every

sonata is preceded by a reading from

three Rosary psalters held in the British

Library. This is a very nice and interesting

concept, as it provides the listener

with the spiritual context in which

these sonatas have been performed. But

one wonders whether the listener wants

to hear these readings every time he

plays the discs, even though the reading

by Timothy West, one of Britain's most

prominent actors, is outstanding in

every way. But they are on separate

tracks, so it is possible to skip them.

Whereas in Beznosiuk's

recording several instruments are used

in the basso continuo part - viola da

gamba and violone, theorbo and archlute,

harpsichord and organ - Sonnerie goes

even further in using also a lirone,

a guitar and a harp. There are different

opinions as to which and how many instruments

should perform the bass part.

The answer to this

question partly depends on where one

thinks these sonatas were performed

in Biber's time. If they were meant

to be performed at the private chapel

of archbishop Max Gandolph, then it

is very unlikely that more than one

keyboard instrument would be used, perhaps

with the addition of a string bass.

Even that practice is only based on

the indication of 'violone solo' in

the bass part of Sonata XII. That doesn't

necessarily mean a string bass is required

in all sonatas.

If one believes that

the sonatas were played in the Aula

Academica in Salzburg, then it is perhaps

possible to imagine a performance with

an additional plucked instrument. Even

so, it seems to me hardly justifiable

to use a harp and a guitar. I haven't

heard or read any evidence that these

instruments were used in Austria at

the time. And as effective the use of

the lirone, with its soft and plaintive

sound, may be in the 'Lamento', the

first section of the Sonata VI, and

in Sonata IX, this instrument - like

the guitar and the harp - was mainly

used south of the Alps.

As there are uncertainties

about the composition and the content

of these sonatas different approaches

are legitimate. And the recordings by

Pavlo Beznosiuk and Monica Huggett are

very different. This is interesting

considering the fact they are both British

and have often played in the same orchestras,

sometimes even alongside each other,

for example in the Amsterdam Baroque

Orchestra.

Pavlo Beznosiuk in

general avoids strong dramatic contrasts.

His tempi are generally slower, and

he is also more moderate in the use

of dynamics. As much as I think this

approach is defensible, I nevertheless

believe there are some major flaws in

this performance. My main criticism

relates to the legato playing and the

lack of differentiation between the

notes. The praeludium of Sonata I makes

that immediately clear: all notes get

equal weight, although it is very obvious

that many notes are only there to link

the really important notes together.

This reflects the baroque principle

of 'music as speech'. In her recording

Monica Huggett is very aware of this:

the clear differentiation between notes

is one of the features of her performance.

As a result her interpretation has a

far stronger narrative character. Baroque

music is basically telling stories,

even though we may not know the stories.

Ms Huggett also uses

a far wider range of dynamics and has

a more flexible approach to tempo. In

general her interpretation has much

more tension than Beznosiuk's, whose

performance is rather tame and pale

in comparison. Although the liner notes

try to explain - in much more detail

than the Sonnerie booklet - the content

of the sonatas and the possible descriptive

traits of them - sometimes rather speculative,

I would say - too little of that is

realised in the actual performance.

In spite of the interesting concept

of adding readings from Rosary psalters

I find it hard to recommend this recording.

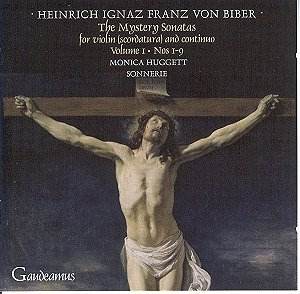

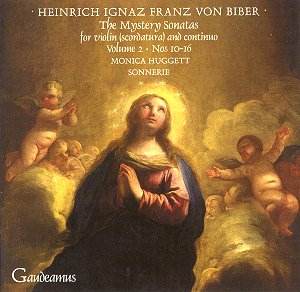

Technically and from

the perspective of interpretation Monica

Huggett is vastly superior. But I have

some problems with her recording as

well. It is certainly legitimate to

approach these sonatas from a more dramatic

angle, but I feel she is going over

the top sometimes. The most striking

example is Sonata XIV: I thought I was

listening to a piece of Italian or Spanish

music, considering the strong dynamic

accents and the percussionistic playing

of the harpsichord and the guitar. It

is all very exciting, but has not that

much to do with Biber. The performance

of the basso continuo part is often

stylistically very dubious: in this

sonata the basso continuo instruments

are far too dominant, sometimes even

overpowering the violin, and there is

a continuous shift from harpsichord

to guitar and back. And in Sonata XI

it is the organ which plays a concertante

role from time to time. Overall the

basso continuo is just too much fuss

and feathers.

When I started the

listening session I was really disappointed

with Pavlo Beznosiuk's performance.

In comparison Monica Huggett's recording

was like a breath of fresh air. But

after a while I started to get annoyed

by those aspects I believe to be unidiomatic,

and in conflict with the character of

Biber's music. I was hoping Monica Huggett

would be an alternative to what was

my favourite recording so far: Reinhard

Goebel and Musica antiqua Köln

(Archiv) AmazonUK.

But I have decided that I have to stick

to Goebel: to me his recording does

most justice to all aspects of these

brilliant sonatas of one of the greatest

composers of the violin of all times.

Johan van Veen