As the timing for this

recording shows, this is one of the

fleetest Mahler Fifths that I know,

though Bruno Walter is swifter still

in his celebrated 1947 recording, which

takes an astonishing 61:04. However,

itís not just the duration of the performance,

occasioned by some fairly swift tempi,

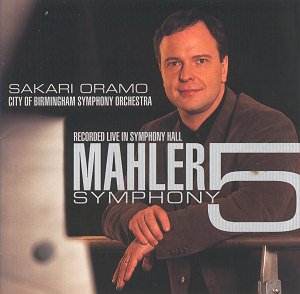

that is remarkable. Taken from concerts

last October (2004), this is the clearest

Mahler 5 that I can recall hearing.

Sakari Oramo seems to be engaging with

Mahler at present for the 2005/6 season

will see him conducting the CBSO in

the first two symphonies as well as

Das Lied von der Erde. It will

be interesting to see if he brings to

these scores something of the same transparency

and clarity that he achieves here.

And that clarity is

important. Writing of this very symphony,

Michael Steinberg has pointed out that

around the time that he was composing

the work Mahler acquired a complete

edition of Bach and was deeply impressed

by the contents. Intriguingly, Steinberg

relates that on the one occasion that

Mahler conducted the Fifth in Vienna

he prefaced the performance with Bachís

motet, Singet dem Herrn ein neues

Lied, BWV 225, a fascinating juxtaposition.

Steinberg argues that from this point

on Mahlerís music became more polyphonic,

influenced, in part at least, by the

composerís appreciation of Bach. In

this present performance Oramo, aided

and abetted by his players, certainly

achieves an impressive degree of clarity

and a significant amount of detail is

revealed.

In this the recording

engineers must have played their part

too. I found that, in comparison with

some other recordings of the work that

I own, I had to set the volume level

a bit higher. But once Iíd done that

the recording has a pleasing natural

ambience. The recording and performance

bring out many little details I hadnít

quite noticed before. The soft percussion

around 4:18 into the first movement

is tellingly, but not ostentatiously,

reproduced. Indeed, the capture of quiet

percussion playing throughout the performance

is a delight. Another example of this

that particularly caught my ear was

the soft bass drum roll 12:04 into the

third movement. Small, even pedantic,

details you may think, but they attest

to the care with which both performance

and recording have been prepared.

But what of the performance

itself? Some listeners may well find

the first of the workís three parts

(movements I and II) a trifle cool.

The opening funeral march, for example,

doesnít have the weight and emotion

that Barbirolli offers, let alone the

angst we hear from Bernstein

in his live DG recording with the VPO.

In terms of comparisons, once Iíd heard

just a couple of minutes of Oramoís

reading I knew there was no point in

even getting out of the jewel cases

either of Klaus Tennstedtís live recordings;

the performances are just too differently

conceived! Oramo impresses through his

refusal to be too emotional and to overplay

his hand too soon. However, if one listens

to Barbirolli or Bernstein in the opening

measures of this work one is conscious

of Great Events being launched. You

donít get that with Oramo and I rather

miss that. That said, itís a finely

detailed reading of the movement and

the CBSO play excellently throughout.

Thereís ample thrust

at the start of the second movement.

Oramo takes the fast music, which predominates

in this movement, very fast indeed.

Despite his challenging tempi, however,

the CBSO cope very well (e.g. around

8:00). Yet, though thereís excitement

Ė of a certain kind Ė Iím not sure that

the music has sufficient weight or bite.

Bernstein, for example, makes the VPO

fairly snarl in places and by contrast

Oramo seems to miss some of the malevolence

that Mahler wrote into some of these

pages. When the chorale occurs near

the end of the movement thereís an appropriate

grandeur though a slightly broader tempo

might have delivered even more.

The substantial scherzo

that lies at the heart of the work is

particularly suited to Oramoís relatively

light touch. Actually, in this movement

his pacing is much closer to what Iíd

expect. I enjoyed the performance and

the CBSOís principal horn player, Elspeth

Dutch, plays her vital part very well

indeed, though sheís not as forward

in the aural picture as Iíve heard on

some other recordings. I suspect Oramo

did not replicate the experiment of

his predecessor, Sir Simon Rattle, who,

in his Berlin recording had the horn

player placed at the front of the orchestra.

Having given us three

pretty brisk movements Oramo springs

something of a surprise by adopting

a traditionally broad speed for the

celebrated Adagietto. Where Bruno

Walter (1947) eased through the music

in just 7:35 and Rudolph Barshai (1997)

was scarcely slower at 8:17, Oramoís

performance plays for 10:01. Oddly,

in terms of tempo at least, heís closest

to the ripe, emotional conception of

Barbirolli here though he doesnít encourage

the same ripeness of tone that Barbirolli

drew from the New Philharmonia. Yet

again he keeps the textures admirably

clear and the CBSO strings play beautifully

for him. At the final climax of the

movement (9:00) the first violins in

alt sound perhaps just a bit thin

but, by contrast, the descending bass

line as the climax passes is projected

very strongly indeed, though not to

the musicís detriment.

In the finale weíre

back to bracing, indeed challenging

tempi. The string-led fugue not long

after the start of the movement is taken

at a real lick. It was in this movement,

however, that I had my most serious

reservations. It just seemed to me that

the music was being pressed too much

and for all their individual and corporate

skill the CBSO do sound under pressure

at times. Worse still, at the extremely

brisk basic tempo several key phrases

fail to make the necessary impact. Frankly,

I thought the music was being rushed

unnecessarily. The apotheosis of the

second movementís chorale is a disappointment

because it isnít allowed to blossom

and flower, as it should. Itís worth

noting that though the track timing

for this movement is 14:42 the music

only plays for 14:05, the rest being

given over to enthusiastic applause.

For me, the slightly less frenetic overall

approaches of Bernstein (15:00) or Barshai

(16:18) are more rewarding.

So, thereís a good

deal to admire in this performance and

I found the clarity of Oramoís performance

very refreshing. Iím sure that in the

concert hall, as a one-off experience,

Iíd have been as delighted as the Symphony

Hall audience clearly was. However,

Iím not sure how well this version,

despite its many merits, will stand

up to repeated listening. In the last

analysis, this is a reading that I admire

in many respects but it doesnít stir

me in the way that Barbirolli, Barshai

or Bernstein do.

In summary, this is

a very well played performance, presented

in very good sound - though you may

need to adjust the playback level. Itís

a very enjoyable recording but I donít

think it disturbs existing recommendations

as a library choice.

John Quinn

see also review

by Patrick Waller