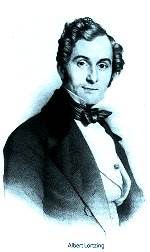

Albert Lortzing was born into a

German theatrical family and was himself

an actor as well as a composer, much

influenced by the style of Mozart and

Weber. Lortzing in turn influenced both

Wagner and Johann Strauss II. Today

he is still remembered for his operettas

which occasionally appear in the mainstream

repertoire. Zar und Zimmermann (1837),

Der Wildschütz (1842) and

Der Waffenschmied (1845) still

play in Germany, but Undine is

less well known.

Undine

is based on a short fairy tale by Motte-Fouqué.

It inhabits a magical world from which

the water nymph, Undine comes. The ethereal

realm of elemental spirits provides

the romantic imagination from which

the opera draws its strength. The libretto

tells how humans who become involved

with the spiritual world will come to

grief and tragedy. The interaction between

reality and fantasy is at the heart

of plots of German romantic opera up

to Wagner. The skilful Lortzing usually

wrote the lyrics for his operas himself,

but for Undine he turned to a

separate librettist, echoing Mozart

who said that ‘in an opera, the verse

absolutely has to be the obedient servant

of the music’. Lortzing was more

down to earth in his views: ‘Operatic

verse! What’s the point of going to

great lengths over it? The composer

has to throw (in) everything that makes

up the poetry ... on to a bonfire, so

that the phoenix that is the music can

rise from the ashes.’ Fouqué

had died two years before the production

reached the public and the subservient

librettist to Lortzing was E. T. A.

Hoffmann.

I find Lortzing’s treatment

of delicate imagery rather heavy and

this is partly due to the fact that

he asked Hoffmann to write a more tragic

treatment of the original story. In

it, a knight, Hugo, falls in love with

a fisherman’s foster-daughter, Undine,

and decides to return with her to his

city to marry her. This is the action

of Act 1. She declares that she does

not have a soul and has been sent by

the water sprite, Kühleborn, to

gain one from human involvement. Much

of the opera concerns Undine’s disclosure

of her origin to Hugo and interaction

with a rival, Bertalda. Undine is later

disowned and returns to the water kingdom.

At the castle festivities for Hugo’s

wedding to Bertalda comes revenge from

the water kingdom (who presumably gain

entry via the castle well). The clock

strikes midnight and the castle comes

crashing down. All but a repentant Hugo

are killed! Hugo is now allowed to join

the sprite’s watery kingdom with Undine

for the rest of his life.

The opera contains

some glorious music yet on an initial

hearing one is not aware of much thematic

development. Lortzing attempted to develop

his own style of singspiel in the same

way that the 19th century

British school tended to promote the

ballad.

Only one other version

is known to me, EMI’s 1967 Berlin recording

by Robert Heger. That has been a benchmark

for this work up to now. Surprisingly,

both recordings have merits, but Heger’s

pacing is sometimes pedantic in comparison

and his balance between sections of

the orchestra is not always good. This

puts the Capriccio recording in a positive

and energetic light: the sound is for

example sharper with the violins more

crisply defined. Of the singers, both

recordings have strong casts, all in

excellent voice and with clear diction.

However, at times I consider the flow

of arched phrases from Monika Krause

rather choppy and staccato when compared

with the breezy flow Anneliese Rothenberger,

forty years earlier. This is most evident

in tr.4 (CD1) of both sets. The chorus

are more fiery in the Capriccio recording

and are helped by the faster pace.

The booklet with very

brief notes is written in German, English

and French.

Raymond Walker