Handel’s Rodelinda

was written for the same cast who sang

in the premiere of his opera Tamerlano;

in fact Handel produced a trio of masterpieces

(Giulio Cesare, Tamerlano and

Rodelinda) in under twelve months.

The presence of tenor Borosini, who

had sung Bajazet in Tamerlano

encouraged Handel, again, to create

a role for a tenor, Grimoaldo, of far

greater significance than was usual

in Handelian opera seria.

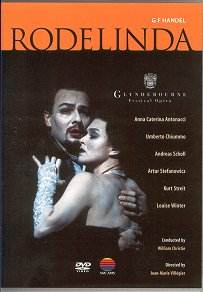

This production of

Rodelinda originated at the Glyndebourne

Festival, the second in their recent

trio of Handel opera productions; the

others are Peter Seller’s production

of the oratorio Theodora and

David McVicar’s Giulio Cesare.

Here, Rodelinda is directed by

Jean-Marie Villegier; but all three

productions have in common an element

of crowd pleasing; the attempt to re-interpret

Handel’s stage works for the Glyndebourne

audience.

Rodelinda has

had quite significant exposure in the

post-war Handel revival because the

plot is rather more direct than that

of some opera seria and has at its heart

the testing of the loving marital relationship

between Rodelinda (Anna Caterina Antonacci)

and her husband Bertarido (Andreas Scholl),

tested almost to destruction by Grimoaldo

(Kurt Streit) and Garibaldo (Umberto

Chiummo).

Given the central role

of Rodelinda and Bertarido’s relationship

and the directness with which Handel

portrays it, it would be possible to

imagine a production of the opera which

told the story in a relatively straightforward

fashion. It could still stick to general

opera seria conventions and be

gripping as drama for an audience more

used to Verdi or Puccini, especially

in a performance as musical and as powerful

as this.

But Villegier, set

designers Nicolas de Najartre and Pascale

Cazales, and costume designer Patrice

Cauchetier set the opera in a world

inspired by early cinema. The stylish

sets and costumes (and makeup) are all

black and white, at first causing you

to wonder whether your TV is acting

up. To go with this, Villegier has encouraged

a stylised, over-dramatic acting style

from the singers so that the opera looks

like a piece of silent film. The result

is surprisingly convincing as a visual

drama, but I did not find it very helpful

in terms of presenting the drama of

Handel’s opera.

Handel gives each of

the major characters a remarkable series

of arias which enables us gradually

to get to know them; this is the strong

point of opera seria, the gradual

delineation of character through a series

of contrasting arias. But this presupposes

that we accept the theatrical characters

as real, suffering people. Thanks to

Villegier’s stylised presentation, this

works only up to a point. That it does

at all is thanks to the magnificently

powerful performances given by this

superbly strong Glyndebourne cast.

Antonacci makes a strong

Rodelinda, no shy retiring flower she,

regal and implacable when necessary;

rich of voice and passionate of utterance

she makes very believable her journey

through despair, desperation and hope.

She looks very glamorous in the sequence

of stunning frocks that Cauchetier designed

for her. She undoubtedly knows how to

use the elaborate baroque vocal line

for expressive purposes, but I found

her voice a little too vibrato-laden

for my taste. When I heard this production

live it was Emma Bell in the title role

and Bell’s more focused vocal delivery

was more to my taste.

In the opening scenes

Villegier very effectively establishes

Streit’s Grimoaldo and Chiummo’s Garibaldo

as the villains of the piece with Garibaldo

driving. Grimoaldo is a weak character,

impelled by Garibaldo, and it is important

that this is credibly established as

it was here. Later in the production,

Streit beautifully conveyed Grimoaldo’s

weakness and hesitation. Chiummo, on

the other hand, portrayed Garibaldo

as almost a caricature of evil; perhaps

Villegier’s stylised conception of the

production did not help. He seems to

have envisioned Garibaldo as the evil

Nazi officer. But surely Garibaldo is

more chilling if less over the top;

still Chiummo did all that the producer

required very creditably with much posturing,

including managing to sing with a lighted

cigarette at the side of his mouth.

The part of Ediuge

(Bertarido’s sister) is a tricky one.

Her part is not deeply written but she

opens the opera being ambitious and

domineering and must make a journey

from an equivocal relationship with

Grimoaldo to disdain and support for

Bertarido. Louise Winter sang Ediuge’s

music beautifully with a lovely, shapely

line, but her disdainful manner was

not always echoed in her voice. This

was Winter’s problem throughout the

opera: her voice did not quite make

the dramatic journey that her character

did.

These opening scenes

were extremely restless visually; something

exacerbated by the camera’s need to

focus on a couple of characters on the

stage. There were many times when I

wished the stage business would just

calm down and leave us to appreciate

the music.

Andreas Scholl’s first

scene was so dark and shadowy that it

was difficult to see his face which

was a shame as his performance of Dove

Sei was wonderful; a lovely sense

of line and shapely phrase allied to

a passionate, focused delivery. Unfortunately

he looked a little bizarre with his

pale white make-up and dark, black hair

and beard. In his second scene Scholl’s

performance is not quite as stunning,

but then he did have to crawl around

the floor.

For these more tragic

scenes, Villegier thankfully quietened

the production down and Antonacci’s

Ombre piante, sung alongside

what she thinks is Bertarido’s tomb,

was superb.

As Grimoaldo, Streit

showed a good sense of style and line,

but unfortunately his passage-work was

sometimes a little smudged. His 2nd

Act aria Prigioniera was lovely,

beautifully conveying Grimoaldo’s soft

centre. It made a fine contrast with

Chiummo’s grim Tirannia aria.

Also in Act 2, Scholl

produced a hauntingly beautiful Con

rauco mormorio, though it was ironic

that Villegier chose to set an aria

full of lovely nature painting on a

dark, bleak stage. The brief reconciliation

between Rodelinda and Bertarido was

haunting but for much of the act there

was too much business and plotting.

This culminates in

Act 3 when Winter’s Ediuge and Artur

Stefanowicz’s Unulfo are plotting to

free the imprisoned Bertarido. Villegier

inserts much laughable stage-business

centred on a tea trolley. For all his

sensitive characterisation of Rodelinda

and Bertarido’s plight, this desire

to introduce a comic element into the

sub-character’s plotting means we can’t

take the opera quite seriously enough.

It does not help that

the character of Unulfo is a little

bit redundant. Necessary dramatically,

Unulfo’s part was made substantial as

it was sung by the second castrato in

Handel’s company, Pacini (who had sung

the title role in Tamerlano).

This means that Unulfo’s dramatically

unnecessary arias are prime territory

for a producer looking to perk up the

stage action. This carried over to Scholl’s

prison scene, when the sudden appearance

of a sword caused an audience laugh.

Still, Scholl’s performance was superb

here.

The part of Bertarido

was written for Senesino, who specialised

in roles which called for long lyrical

lines, his characters are often lovelorn.

Scholl handles this aspect of the character

very well and the music seems to suit

the timbre of his voice. But for the

resolution to Rodelinda and Bertarido’s

problems, a triumphal aria is needed

and Scholl rose to the occasion brilliantly

producing fine trumpet tone for Vivi

tiranno.

This triumphal ending

is made all the more poignant as earlier

on in the act, Rodelinda again thinks

that Bertarido is dead and Antonacci’s

grief at this point was palpable.

For all my complaints

about the production style, this DVD

works because the principals all give

strong performances. Antonnacci and

Scholl in particular make the strength

of Rodelinda and Bertarido’s relationship

strongly believable and the key to the

whole drama.

The Orchestra of the

Age of Enlightenment under William Christie

give a fine performance, imbuing Handel’s

accompaniments with the necessary crispness

and bounce.

In terms of extras,

the DVD is a little disappointing; there

is a printed plot summary and you can

select individual scenes but that is

about it, DVD’s of commercial films

usually come with far more.

For its musical values

alone this DVD is highly recommendable.

For many people, the production values

will not be the stumbling block that

they are for me and I hope that the

disc will generate new admirers for

what is one of Handel’s finest operas.

Robert Hugill