In 1767 the Music Director of Hamburg,

Georg Philipp Telemann, died. As his successor, his godson Carl

Philipp Emanuel Bach, was appointed. One of his duties was to

compose and perform a setting of the Passion every year. In

Hamburg the Passions were performed in a four-year cycle, in

which the Gospels alternated, starting with St Matthew and closing

with St John. Bach asked Telemann's grandson, Georg Michael,

who had taken over his grandfather's duties for the time being,

what the circumstances of Passion performances in Hamburg were,

assuming his first duty was to compose a Passion for 1768. But

his departure from Berlin was delayed and he arrived in Hamburg

shortly before Easter 1768. Therefore his first Passion was

the St Matthew Passion of 1769.

Passions in Hamburg were considerably

shorter than elsewhere. There were two reasons for this. Firstly,

the Passion was performed during a regular service, not as part

of a special Vesper service - as in Leipzig, for instance. In

addition, many members of the congregation didn't enter church

before the sermon started. Therefore it was decided to perform

the whole Passion after the sermon, whereas originally Passions

were divided into two parts, to be performed before and after

the sermon respectively. As a result the Passions written for

Hamburg started with Jesus and his disciples going to the Mount

of Olives, and ended with the Crucifixion.

The circumstances under which Bach

had to produce the Passions were less than ideal. The Passion

had to be performed in the five main churches within a couple

of weeks, and the Music Director was also responsible for the

Passion music in the subsidiary churches. But he had no more

than eight singers and fifteen instrumentalists at his disposal.

One of the features of Bach's Passions

is the use of music by other composers. One of the sources of

Bach's borrowings was his father's St Matthew Passion. In particular

Johann Sebastian's settings of the turbae and chorales were

incorporated into Carl Philipp Emanuel's Passions. In his first

settings they are used practically unaltered, but from the second

half of the 1770s on he started to rework them, in order to

create a greater stylistic unity within his Passions. In the

St Matthew Passion of 1785 we find a number of passages which

sound very familiar to our ears - not, of course, to those of

the Hamburg congregation, which had never heard the old Bach's

Passions -, but in most cases something has changed, for instance

the harmony or the instrumentation. He took over some hymns,

but on a different text, or he put them in a different place.

Sometimes the upper voice remains unaltered, but the other parts

have been changed. In some turbae Bach uses the same rhythm

as his father, but on different music. In others he keeps the

basic structure, but changes the instrumentation.

There are also considerable differences

between the Passions of Johann Sebastian and Carl Philipp Emanuel.

First, the Passions of the latter are far less dramatic, and

much more lyrical, which is especially demonstrated in the choruses.

It is here where Carl Philipp Emanuel uses stanzas from newer

hymns. Since the chorales were sung by the congregation he could

use only those melodies and texts which were printed in the

Hamburg hymn book which was unaltered since 1700.

Another difference is the number

of arias. In this Passion there are just three: two for bass

and one for tenor, with one arioso for soprano. The texts reflect

the spirit of the Enlightenment. They are of a more reflective

and rather moralistic nature, like the aria 'O grosses Bild

des Menschenfreundes': "O great image of a friend of man,

gaining salvation for his enemies, come, from him learn about

love (...). Do not desecrate religion through impetuous forces

of revenge."

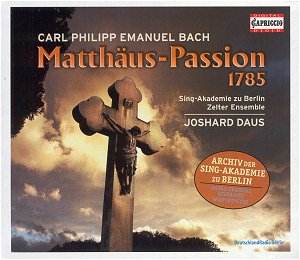

It is good to have a recording

of this Passion, which is part of the archive of the Berlin

Singakademie. The archive disappeared at the end of World War

II and thankfully was rediscovered in 1999 in Kiev. But I wish

the performance had been better. The main problem is not that

the orchestra is playing on modern instruments, although that

is disappointing. It does its best to play like period instrument

orchestras, but does so not very convincingly: even the leader,

the seasoned baroque violinist Florian Deuter, can't really

change the traditional playing style. A bigger problem is the

choir, which is far too large, lacks clarity and flexibility

and produces a sound which is too thick and massive.

The recitatives are sung in tempi

which are generally unnaturally slow. The singing of Thomas

Dewald and Daniel Jordan is too traditional and vibrato-ridden.

Jochen Kupfer is the only participant who is thoroughly convincing

in his stylish performance of the two bass arias.

This St Matthew Passion deserves

a much better performance than it is given here.

Johan van Veen

![]() Isabella Stettner, soprano;

Thomas Dewald (Evangelist), tenor; Daniel Jordan (Jesus), Jochen Kupfer,

baritone

Isabella Stettner, soprano;

Thomas Dewald (Evangelist), tenor; Daniel Jordan (Jesus), Jochen Kupfer,

baritone![]() CAPRICCIO 60.113 [55:01]

CAPRICCIO 60.113 [55:01]